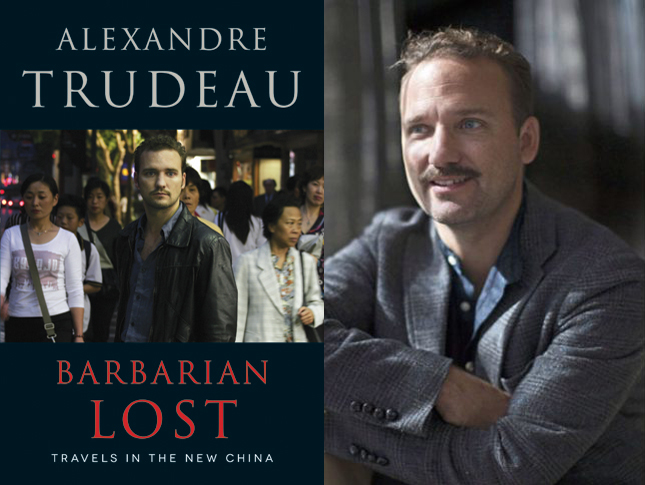

One-on-One with Alexandre Trudeau

In a one-on-one interview with Zoomer, Trudeau discussed his father, his relationship with his Prime Minister brother Justin Trudeau, why he can’t take a regular vacation and his new book Barbarian Lost: Travels in the New China.

Alexandre Trudeau, known affectionately as Sacha, didn’t see much of China during his first foray to the Far East in the 1970s with his famous parents—Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and former Zoomer cover subject Margaret Trudeau—given he spent the entire trip tucked away in his mother’s womb.

Of course, in the ensuing years his infatuation with the country grew as he saw more of it, both as a child visiting with his father and older brother, future Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and on numerous trips through the country as an adult. Rather than spend his time snapping selfies at the Great Wall, though, Trudeau explored some of the farthest corners of the vast land, visiting with everyone from rural labourers to the artist Ai Weiwei in cities and small towns along the way.

“You can stumble off the beaten path, you can see deep China but, like all trips, it requires a kind of commitment, a vulnerability,” Trudeau, 42, tells me in a hotel bar in downtown Toronto when discussing his new book Barbarian Lost: Travels in the New China.

“I understand that I was just born that way. I like that, being stripped down, I like sleeping with the rats … It’s for the traveller, not the tourist. I think the tourist will find it bewildering and not necessarily easy to love. The traveller will become mesmerized by it.”

In his new book, Trudeau chronicles his travels across the country, the people he met and the changes – social and economic—that he witnessed. And despite the fact that his Prime Minister father opened up diplomatic relations with China in 1970 and his Prime Minister brother recently returned from his first high-profile diplomatic visit to the county, Trudeau managed to slip across the nation anonymously, his famous surname failing to raise many eyebrows.

Still, Alexandre Trudeau remembers the words of his father: “If there’s one place you don’t want to jump to conclusions in, it’s this one. That’s barbaric as well, thinking you can understand and know China quickly and know what’s best for China.”

Zoomer’s one-on-one interview with Alexandre Trudeau continues on the next page.

Your father famously opened up China, diplomatically, in 1970. Is this book a way of opening up China, ideologically, to a new generation?

ALEXANDRE TRUDEAU: Yeah, I think so. When my father recognized it, China was an outcast—a country that wasn’t participating in the world economy…Now China’s in our lives in so many different ways. It’s revolutionized our consumption. We’re wearing so many things and surrounded by Chinese products so that’s really a challenge to us, to understand where it’s all coming from [and] what role this place plays in our lives.

There’s still a hesitance, though, among many in a democracy like Canada, to encourage trade and relations with a nation that we perceive as being rife with corruption and injustice.

AT: We look at China through a very narrow prism of the society we have and what we want without understanding how we got there, from the Magna Carta to the parliamentarization of monarchies. The west’s pressures were dealt with through expansion. The Americas were the expansion. So the freedoms that went with them don’t look so beautiful always when you really look at how they were built—slavery, subjugation of people, territorial expansion. China didn’t do that and therefore it’s under a lot of pressures that frankly [don’t] bare well for individual freedoms. The individual is becoming more developed in China now. That’s part of the economic freedoms that exist there. And the political questioning is beginning to happen.

[Canada has] reason to be a sophisticated and independent player who can entertain complex relationships with countries that are not politically and ideologically necessarily close to us but who are significant world players. And we can play a role in helping them evolve towards societies more like ours—tolerant, multi-cultural, open-minded, non-ethnically driven. And it’s not by being shut away. If we didn’t trade with people we disagree with sometimes we’d trade with no one.

What do you think your father would say about your work in China?

AT: I’d like to think he’d appreciate it deeply. He got to see the beginnings of my work as a filmmaker and he loved it. He was very supportive. So I pay tribute to my father because I feel he’s with me. I’m following his wisdom. I’m still growing wiser through him.

On a more personal note, the book illustrates part of your childhood relationship with your dad. What did you learn from him about being a father?

AT: He was a strange kind of father in that he was 53 when I was born. I certainly learned that that’s not what I wanted to do because he left the world without ever having met his grandchildren. I think that’s sad. So I felt it important to have a family younger. But as a man who was well into his life when he started to have children, there’s some great advantages to that. You know deeply who you are and you’ve achieved a lot more and therefore in a way you’re more accepting of your children.…Looking at my father made me reject the notion that I would ever choose between my family and my work. It’s humbling but being a parent is a source of wisdom and one of the things I live for is to grow wiser.

You spent years travelling anonymously to remote corners of the globe. How does it feel, with your brother as the Prime Minister, to be back in the spotlight as part of Canada’s first family again?

AT: I’m glad for it because it’s allowing my books to find readers that they might not find otherwise. I have a lot of respect for my father and I owe a lot to [his surname]. It’s a little weird—for a long time it kind of annoyed me, which is why I love the anonymous, obscure travel where I was a poor nobody and people who encountered me [did so] on truly my own terms. So there’s a positive/negative side. I’m more at peace with it now. I have my own body of work, I know what I know, I don’t feel my identity is so linked to that. And this book is certainly a great achievement for the real me in that that’s really the real me.

Your brother read your book before his recent trip to China. Now that he’s Prime Minister, what’s your relationship and interaction like with him?

AT: My brother and I have a very playful relationship and continue to. I remain in the space—and that’s a very small space now in his life – that’s completely outside of politics. I’d laugh at him if he tried to perform for me. He doesn’t have to perform. So we play with our children. He read my book, he knows what I think. I can’t imagine that we’re sitting around discussing how to get an angle on China in a trade negotiation. If I did that, it would be at a cost to our sanctuary that we have, which is I’m part of his world outside of politics. And it’s not my place to do that.

Given your explorations in deep China and other less-traveled locales, are you able to just vacation on a beach with an umbrella and drink?

AT: No, I can’t do that. My time off is time in the woods with my chainsaw, clearing land, planting trees. Or my travel vacation is some deeply involving journey, like climbing into the four or five thousand metre range so I can find rhododendron in the beginning of the Himalayas. That, for me, is escape in the vacation sense. But no, sitting on the beach – can’t do it, to my wife’s chagrin. There’s no turning me off, unfortunately.

Barbarian Lost: Travels in the New China is available in stores and online.