Salman Rushdie’s Latest Novel Uses Trump Election As Backdrop

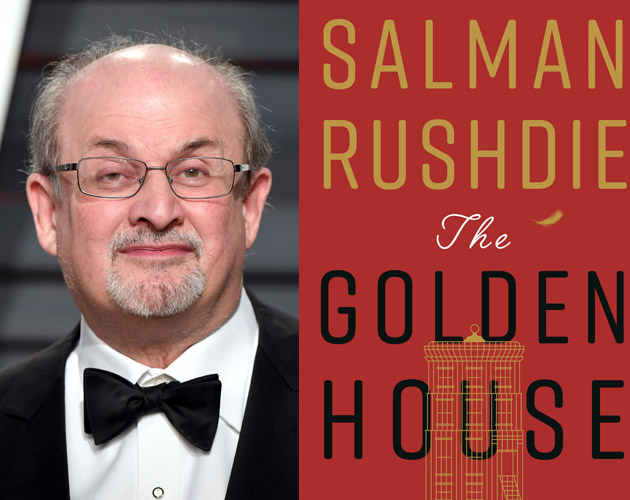

Photo: Getty Images

If you read one book this fall, it should be Salman Rushdie’s splendid The Golden House.

It’s the story of a wealthy South Asian man and his three adult sons who emigrate to Manhattan from Bombay.

The men, their women, their business associates and their neighbours in the Garden district are richly and intimately drawn on a canvas that is contemporary America, from Obama to Trump.

He never mentions Trump by name but includes a presidential candidate he calls the green-haired white-skinned Joker.

“…on one fact everyone, passionate supporters and bitter antagonists,was agreed: he was utterly and certifiably insane. What was astonishing, what made this an election year like no other,was that people backed him because he was insane, not in spite of it.”

Typically mischievous, provocative and offensive (to Trump and the American alt-right), occasionally outrageous and laugh-out-loud funny, but also deeply philosophical and compassionate about the human condition, The Golden House is a must-read that’s likely to garner the author his fourth Booker Prize nomination and quite possibly his second Booker Prize win.

We spoke shortly after the Charlesville, Virginia white nationalist rally.

Q: The Golden House has been described as part Bonfire of the Vanities, part Godfather and part Great Gatsby. Would you agree with that description?

A: “Well, it’s difficult for it to be The Godfather and Bonfire of the Vanities and The Great Gatsby. The point is the book is consciously referential to a lot of things and, yes, there are Mafia people in it. One thing the novel has in common with Gatsby is the reinvention of oneself. Here you have this family of men exiling themselves.”

Q: Is it an epic? A comedy? A tragedy?

A: “The answer to all that is, yes. It owes a kind of debt to Greek tragedy. It’s a novel conceived on a big scale, a big panoramic novel of the present moment. It’s always a risky thing for a book to take on the exact present moment. We live in age so fast moving that the book could be out of date by the time it comes out. But I was hoping to capture a moment for all time.”

Q: The book covers the time period of Obama’s presidency, 2008 to 20016, but it is amazingly prescient about what has been happening since Trump’s election. You never mention him by name but there are many references to a mad Joker and also to a glamorous Eastern European gold digger.

A: “The tapestry of what’s happened in America is the background against which the story is played out. I certainly didn’t see the speed and extent of the horror that would follow the election. Even to those of us who were clear about what Trump is like, the speed of the meltdown of America is shocking. The mood of the country is very angry and violent, with all of that fuelled by the presidency. I do think he is a racist with dog whistles to his followers on the extreme right. American is finding out what New Yorkers already knew.”

Q: To what extent do you identify with Nero Golden, the patriarch of this South Asian family of men who exile themselves in New York and a man who struggles to reconcile the good and evil in himself?

A: “I think it’s clear that the characters you write about come out of yourself or your interaction with yourself. The characters became extremely vivid to me. They came to inhabit me. And it’s a very pleasant surprise how many people really like my Russian gold digger. I guess she’s seductive.”

Q: The novel is intentionally cinematic and you have many references to the film world and movie industry, some of them very funny. You’ve been a movie actor and scriptwriter. What is your relationship with Hollywood?

A: “Hollywood hasn’t beaten a path to my door. I don’t think that all my books are cinematic, but let’s see if anybody is interested in this one. I loved making the film (Midnight’s Children) with (Toronto filmmaker) Deepa Mehta and I would like to do an original screenplay. But when Deepa and I were going around (for funding) they told us, ‘We admire you as a film director so much and we will back it 1000 per cent’ and they never gave us a red cent. The level of bullshit is very high.”

Q: One of your characters works as the Director of the Museum of Identity. How do you feel about the current emphasis on identity politics?

A: “The whole gender issue, for example: if people are able to define identity in more varied ways, that is a good thing. (On the other hand) white America is becoming afraid of the fact that quite possibly they will not be able to run the place anymore because quite soon the white population will be in the minority. There is some segment of white America that was not able to stand that there was a black man in the White House.”

Q: What do you hold sacred?

A: “The great things of human life: love, truth, art. And not just romantic love—love for my children, my sister and a group of very close friends, love of family, love of country. Love is one of the great things about being human, even when love goes wrong as love often does.

And I care about the truth. It’s very strange for a writer of fiction to be obliged to insist that there is such a thing as truth. It’s very dangerous for a democratic society if you don’t have truth. I also think it’s very strange that academics and writers are considered elitist when you have billionaires in government and they’re considered to have the common touch.”

Q: What question do you get asked that you dislike most? And what pleases you most?

A: I still get fatwa questions and I point out two things: One, that it’s been over for 20 years, and two, that I’ve written a 600-page memoir about it (Anton Joseph) which they’re welcome to read. I do like it when people talk about comedy in my work. I don’t even like reading books that lack some degree of humour. It gets in my way with colossal great novels like Middlemarch.”

Q: How did it feel to leave the Goldens behind when you finished the book?

A: “Finishing a book is like having three-quarters of my brain removed. I’ve been occupied with nothing else and then it goes off with a little puff of smoke, It feels like a lobotomy, so I get on with daily life, read books and wait for the brain to return. I like it when a book is published if I have something else on the go. I have a project to do a television adaptation of E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India. When I was an undergrad at King’s College (Cambridge), I was able to meet him. He was 89 and I was 17. He was a very sweet and open man.”

Q: You’re 70 years old. How do you feel about aging?

A: I’m not a great fan of getting older, but I don’t object to it. When people say 70 is the new 50, I don’t agree: 70 is the same old 70. What it does do, which is valuable, is that it concentrates the mind. What it does for me: It tells me, ‘Don’t waste your time. Think about what you want to get done and don’t mess around.'”

Or, as Rushdie writes in The Golden House, “think of life as a novel, let’s say a novel of four hundred pages, and then imagine how many pages in the book your story has already covered.”