Whether it’s a municipal pool, a secluded backyard oasis or that moment when you first crest the hill and see the lake, there’s just something about water. Because with water, there’s the promise of swimming.

Whether it’s front crawl or breaststroke or luxuriating skyward with a backstroke you stretch out and the desk slouch unfurls. The buoyancy of the liquid medium offers total relaxation. In the streamlined gliding moment after every stroke toward the horizon edge there is a feeling of forever — until the next stroke. And the next. The strokes multiply. The rhythm of the horizontal pace timed with breathing patterns becomes meditative.

With the addition of goggles, the underwater view changes — and with it, perspective. In a swimming pool (or as the outdoor ones are called in Europe, lido) looking up at the sky through the veil of the surface, the clear blue turns into silvered bubbles, like mercury glass. In wild swimming, there’s the shock of the cold water that leaves you alone with your thoughts and urges you to push through them, to the inky dark depths beyond.

“When you enter the water, something like metamorphosis happens,” Roger Deakin wrote in Waterlog, still a pillar of the swim-noir genre. “Leaving behind the land, you go through the looking-glass surface and enter a new world, in which survival, not ambition or desire, is the dominant aim.” There’s a simplicity and peacefulness to that survival, that buoyancy that cuts across class and age and has no judgment. Because the social conventions around the water have varied through history, but water itself remains indifferent.

Many have before and after Deakin have written eloquently about swimming but the more recent literature of swimming zeroes in on the female experience, with the activity as a means of recapturing one’s true identity. In Gillian Best’s novel The Last Wave (House of Anansi) for example, a young wife and mother in the 1940s escapes domestic drudgery and even stops attending religious services (“this is the only church I need”) because of her obsessive devotion to swimming. “Nothing could keep her from the sea because it was her answer to everything … The sea, for my mother, would make it all better.” Breaking the surface of the water also offers the welcome relief of the solitude and isolation in Claire Fuller’s Swimming Lessons (House of Anansi) — another reluctant matriarch inexorably drawn to the sea, this time in Dorset, and passages that deal with water and evoke this quality of it.

In 1918, Australian swimmer and silent film star Annette Kellerman published the How to Swim manual, touting it as the best sport for women because it supposedly expresses innate femininity, elegance and grace. Kellerman was wrong: swimming is the best sport in the world for women because it’s magic. It’s meditation. And that has nothing to do with body confidence. Women in water is the one place there can be no so-called second shift, no multi-tasting — the focus is on feeling yourself in your body. It’s entirely free of duty.

At least one thing Kellerman got right: “Swimming cultivates Imagination.” Joints and muscles are submerged in water but so is the brain, and the activity has mental health benefits. The flashes of dappled light bring with them a calm that can quell anxiety.

Last summer an independent study commissioned by Swim England touted the health and well-being benefits of water, not only for those with long-term health conditions; it also found evidence of helping the elderly stay physically and mentally fit. For her compendium The Mermaid Handbook, Carolyn Turgeon revisited several of the former teenage ‘mermaids’ who worked at Florida’s Weeki Wachee Springs 1950s theme park.

“All these aging women talked about that weightlessness in the water, of going into the water and feeling like they were 17 again,” Turgeon told me of her interviews with the women, now all in their sixties and beyond. “It’s in a way you don’t feel on land. That sort of magic quality where you don’t have age is appealing.”

“Rosemary is 86 but in the water she is ageless,” Libby Page writes in heartwarming new novel The Lido (Simon & Schuster) about the intergenerational friendship between a lonely young journalist and a seasoned octogenarian swimmer. They bond over the transformational effects of swimming when their Brixton community lido is threatened with closure. At one time there were nearly seventy such lidos London.

In the recent movie Finding Your Feet starring Imelda Staunton and Celia Imrie about sisters and second chances, they swim in one of them. The famous Kenwood ladies’ pond on Hampstead Heath (also a favourite of North Londoners like Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter) becomes emblematic of Imrie’s free-spirited sexagenarian character.

Winner Of Female Diving Contest Blandine Fagedet at the Swimming Pool Georges Vallerey In Paris, 1962. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Winner Of Female Diving Contest Blandine Fagedet at the Swimming Pool Georges Vallerey In Paris, 1962. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

The elemental nature of swimming and female identity is also something that Under the Tuscan Sun author Frances Mayes touches on her latest novel Women in Sunlight. It’s the story of writer Kit and a group of American women who are all at a life crossroads, spending a year near Venice.

“I duck into the cabin and take out my notebook. What words fit this place?” the writer observes. “I jot down: shimmy, glimmer, shimmer, labyrinthine, a thousand mirrors, stippling, mercurial, elegantissima, gnarls of water, spumes like angel wings, water, water everywhere.” This is all before Kit even dives in, and when she does: “The water feels luxurious and fresh…. To somersault, backstroke, kick, to bind yourself tightly to yourself and roll on top of the water—this is a joy we were born for.”

“There’s a great chunk of time when women only appear in the swimming story as mythological creatures,” Jenny Landreth says, “and you have to wonder why mermaids were invented.” Mermaids possess magic, in that they supposedly lure innocent men to death and conjure the mysteries of the unfathomable deep they visit, one that humans cannot reach. As Landreth outlines in Swell: A Waterbiography, they were drowned as witches (trial by water was an unofficially accepted way of ‘weeding out’ witches’) or function as victims of the male gaze.

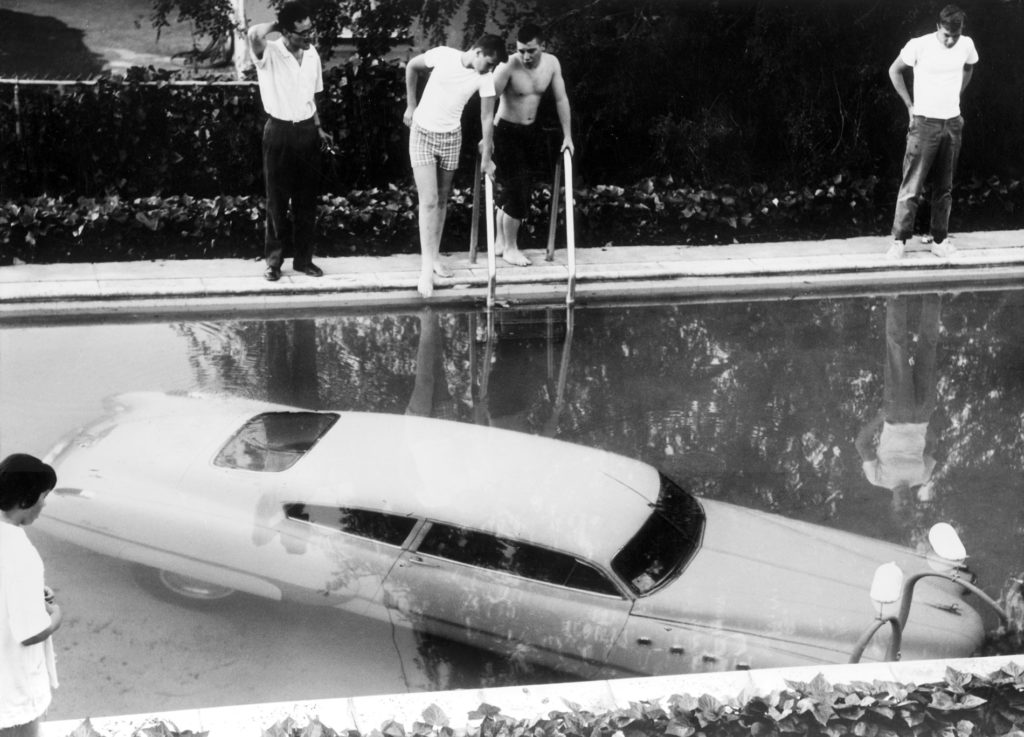

Car Pool: A submerged car which its drunken owner ‘parked’ in a swimming pool in Beverly Hills, California, believing it to be a parking space. Nobody was injured in the process. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Car Pool: A submerged car which its drunken owner ‘parked’ in a swimming pool in Beverly Hills, California, believing it to be a parking space. Nobody was injured in the process. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Landreth’s entertaining cultural swim-moir examines the feminist history of the activity — swimming suffragettes, as she calls its early practitioners like Kellerman and before her, Queen Victoria, who in 1847 became the first royal woman to swim for pleasure (as opposed to health). Initially, women of her era swam with the aid of modesty-preserving Victorian bathing machines (wooden carts rolled into the sea), where they waded while wearing the equivalent of layered flannel nightgowns, because women’s unclothed bodies were once considered a public danger. That’s another aspect of swimming still too relevant today, with burkinis being outlawed and the policing of swim attire for the opposite reason.

Because swimming is a sport, it’s recreation, and it creates powerful images.

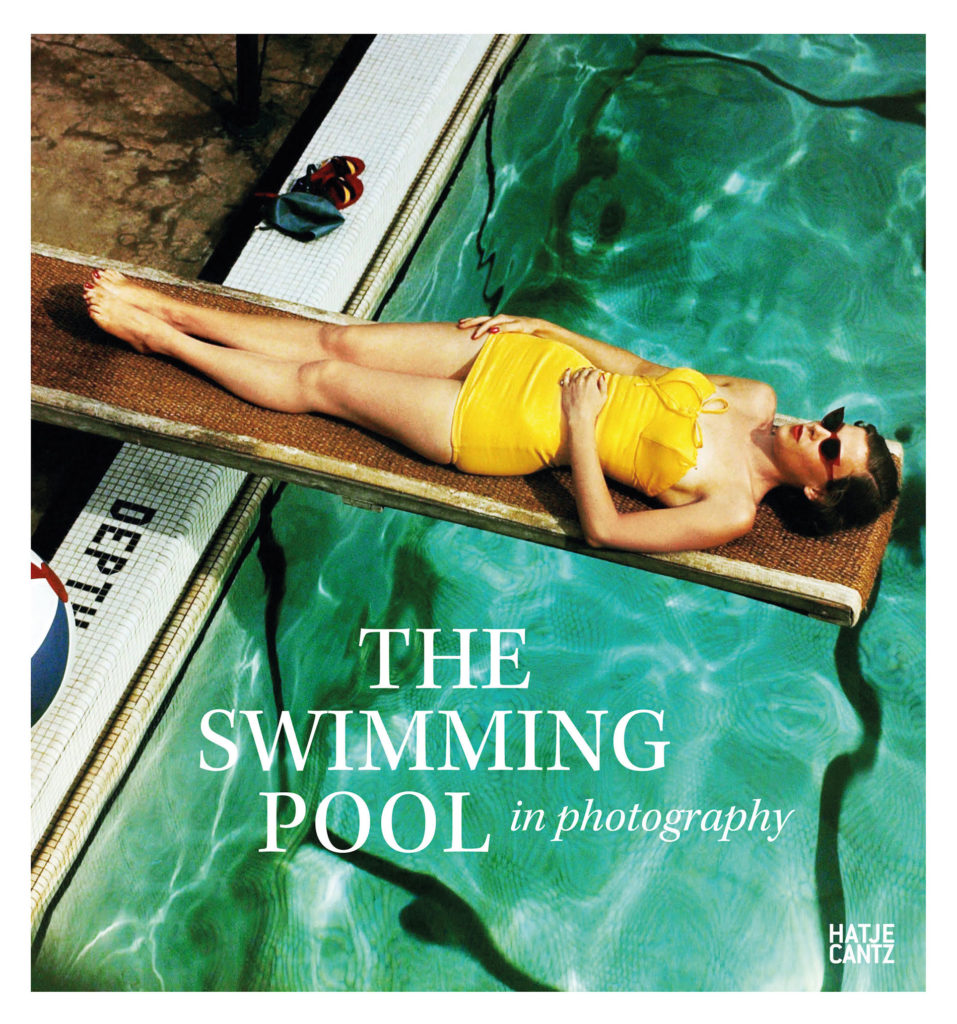

“Water is a metaphorical gift, of course,” critic Francis Hodgson, former head of Sotheby’s photographs department, explains in his sumptuous new coffee-table tome The Swimming Pool in Photography (Hatje Cantz). “In mythology, it is routinely the place where transformation happens: sirens and selkies and mermaids and baptism and the birth of Venus…Even in the relative tameness of a pool, water is a gift to a photographer: it gives near-nudity, and it gives light, both at the same time. No wonder photographers love pools.”

And do they: the photographs Hodgson features range from Slim Aarons society set and Hollywood and notably, fall into two camps – the “almost military exercise” of laps in a rectangular swimming pool, compared to the more playful social activity around the freeform kidney bean, shaped for leisure and pleasure rather than fitness (think the decadent revels of bright young things dancing around Jay Gatsby’s lavish oasis). The pool is a potent and complex symbol, particularly as articulated fifty years ago by Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer, the 1968 movie based on the John Cheever story; his distraught character Neddy traverses ten backyard pools (and an existential lifetime) that represent his failed suburban aspirations.

With contrasts between labyrinthine waterslide parks and serene infinity pools, 1950s American motel kitsch and Eastern Europe’s historic public baths, and elaborate springboards with divers suspended mid-air and celebrities like aquamusical superstar Esther Williams posing as poolside pin-ups, if Hodgins’s comprehensive historical collection of pool photography doesn’t inspire you to suit up and jump in this season it’s likely nothing will.

And when taking the waters, try and experience swimming with a new mindfulness, remembering the way Landreth characterizes swimming as ‘blue silence.’ Because when you swim you let the day go — everything is water. When you pause and float, weightless, the water holds you. “A good swimming pool could do that,” Emma Straub writes in The Vacationers; “make the rest of the world seem impossibly insignificant, as far away as the surface of the moon.”