A new multi-media art project seeks to demonstrate the human factor in global environmental decline.

There’s a countdown clock on a computer in photographer Edward Burtynsky’s Toronto studio. It ticks the minutes and seconds until the September unveiling of Anthropocene, the multidisciplinary collaboration between Burtynsky and filmmakers Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier. Between them, they’ve made documentaries about The Tragically Hip’s last tour (Long Time Running), Paul Bowles (Let It Come Down) and debt (based on Payback, the Margaret Atwood lecture) and Burtynsky is renowned for his awe-inspiring and often abstract images that document sites where nature meets industry.

Coined in 2000 by Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen, anthropocene is the new proposed name for our present geological epoch by the Anthropocene Working Group (AWC), an international group of scientists advocating to officially change it from the current designation, the holocene. The new prefix comes from anthropos (the Greek word for human) because it would distinguish it in the formal geological time scale from the last major ice age and emphasize the undeniable enormity of being the first species with a planet-scale influence.

As explored by Burtynsky, Baichwal and de Pencier, the Anthropocene project combines art, film, virtual and augmented reality with scientific research to investigate the human influence on the state and future of the planet with dynamic, thought-provoking experiences of some of the planet’s most difficult locations. The exhibition portion, which includes 30 large-format Burtynsky photographs and new high-resolution murals on a massive scale, opened simultaneously at the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (on Sept. 28) and will travel to Bologna next spring.

Carefully packed art cartons lean along one wall on the eve of exhibition as Burtynsky oversees last details and flips through a proof of the Anthropocene book, which contains a new suite of original poems by Margaret Atwood (coming in November). At their midtown studio, filmmakers Baichwal and de Pencier have been working on sound and colour correction for the Anthropocene feature documentary ahead of its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival (it was recently released in theatres across Canada on Oct. 5), but the trio take a break from final preparations and gather around the bright red desk in Burtynsky’s office to talk about how the various media are all part of a piece.

“They’re all ways of trying to extend the experiential, non-didactic nature of the photographs and the film,” Baichwal adds. “They’re meant to be an experience where we take you to places that are thematically important that are part of that bigger equation.”

Between the climate crisis, altered environmental conditions and imminent threat of mass extinction it covers, the countdown clock could also easily refer to the project’s subject. But it’s an environmental equation where the modus operandi is not finger-wagging. “It’s really to get people to expand their consciousness around this. And to get outside of the established lines of discourse that are pretty entrenched around environmental issues that become political,” de Pencier says. Anthropocene is less a condemnation of humans as a planet-scale disruptive force than an experiential call to awareness about the long-term cost and consequences.

“One of the key things,” the photographer adds, “is that the work moves toward being revelatory, not accusatory.”

Designated markers throughout the gallery spaces trigger tablet and smartphone installations made with photogrammetry (the process of creating complex dimensional augmented reality with specialized measurement software) and launched through the window of AR technology. “With video or with stills, you’re fixed,” Burtynsky says, “the gaze and the view is fixed. You can move back and forth at a detail, pull back or not. But engaging with an augmented reality piece, you’re the protagonist. It isn’t a fixed frame, and you’re moving through, experiencing it, trying to understand it.”

That includes understanding our role as catalysts. Scholars and scientists of the AWC put the epoch’s beginning around 1950. “Exactly the boomer generation,” de Pencier points out. “In the past, start dates have been meteors and ice ages but, for these scientists, the boomers are the anthropocene generation.” The idea is that everything that we do has now tipped the planet into a place that has no historical analog, Burtynsky chimes in, “with 2.5 billion people in 1955 at the peak of the boomer generation, now we’re almost at 8 – that’s almost a billion [more] per decade that’s happened in our lives, so we are the witnesses of the great acceleration.”

“And the participants. We’re driving it, and our relationship with China, we’re driving that,” Baichwall continues. “The project is a way of making us aware of those connections, how we are all integrated into this.”

Burtynsky’s detailed, large-format aerial views of melting glaciers, oil sands and polluted rivers that show impact and scale are in prestigious institutional collections around the world. “But the thing about images is that they’re kind of mute,” Burtynsky ventures, “and they can be misinterpreted very easily as estheticizing ‘disaster.’ With Jen’s and Nick’s talents through interpreting one medium – stills – through the medium of film, they were able to extend the context of what I was doing and really get the viewer to appreciate it. You never see Made in China in the same way again. I don’t think that response could have happened with the stills alone.”

He’s talking about their first collaboration 13 years ago on Manufactured Landscapes (2006) about Burtynsky’s work in China; next came Watermark (2013), the internationally acclaimed “rhapsody of environmental horror” (as one critic put it) that won the Rogers Best Canadian Film Award.

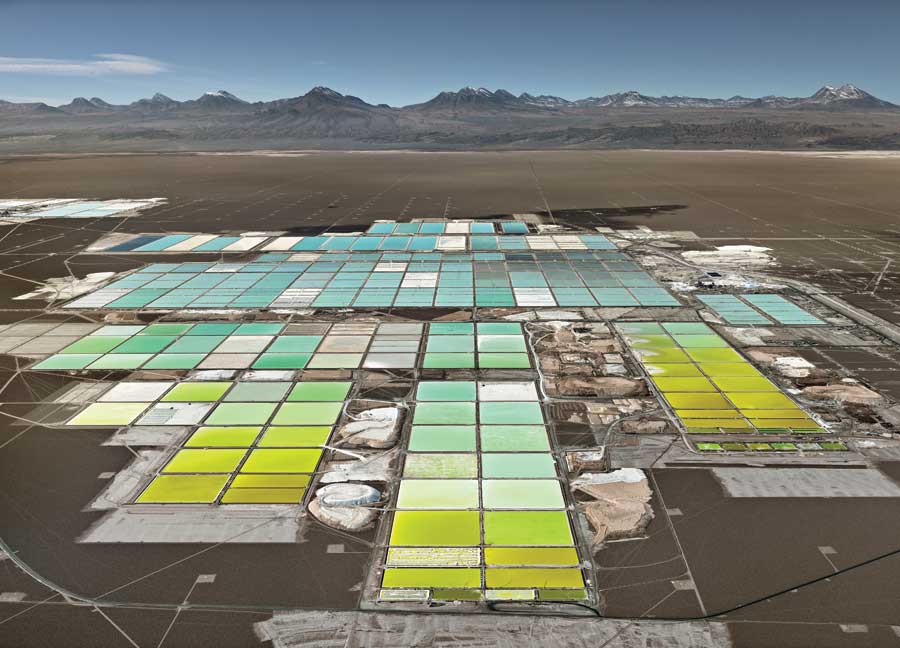

Work on Anthropocene, the finale of this informal trilogy, a culmination of career themes, began in 2014. The four-year journey took the team through 20 countries to remote places that aren’t likely to be on anyone’s bucket list, from the Berezniki underground potash mines in the Ural Mountains to the lithium evaporation ponds of the Atacama desert. The project is loosely structured by the AWC’s various categories, and Pencier recalls how the “war room” in Burtynsky’s house was covered in images from each research category “to see what has the most depth and resonance and visuals.”

Sites like Norilsk, the closed industrial city in Russia that was originally a gulag prison labour camp made the cut. It’s one of the most polluted cities on the planet and the world’s largest producer of palladium (the rare mineral used in cellphones). Located above the Arctic Circle with its perpetual daylight, the quest for softer light meant they had to shoot at 3 a.m. “The weirdness of wandering around that place in the middle of the night feeling like in the middle of the day with nobody around because it was abandoned,” Baichwal says, “and getting detained and fingerprinted for talking to women in the copper smelter! That kind of stuff was pretty incredible.”

The trio’s past cinematic collaborations have made use of the latest lens and shooting techniques, like drone technology or gyro-stabilizing Cineflex cameras; they also obtained a prototype of the Google JUMP Odyssey 3-D 360-degree virtual reality camera system (with 16 radial cameras and stereoscopy algorithms for image stitching). The Anthropocene exhibition extends from the medium of stills further into what Burtynsky dubs photography 3.0, or the third dimension, through gigapixel essays and borderless 360-degree films that bring the viewer and subject starkly back down to the earth.

“As a medium, film is expressing scale and time, detail in time and being able to have emotional interaction with what you’re looking at,” Baichwal says. The VR/AR extensions are immersive in another particular way that contextualizes scale and detail. “You can be looking at a huge city of Lagos on the murals, and then you’re on the street walking right there and you feel it in a different way.”

“We did a photogrammetry capture,” Burtynsky enthuses about one memorable shoot mapping an underground mine in Siberia that generated more than 20,000 high-resolution images. Once stitched together in a virtual world, they offer a complete filmic recreation of the mine. “It’s not a built world. It’s not synthetic,” de Pencier adds. “It is actually what was there.” Similarly, a detailed underwater coral wall shoot in Komodo, Indonesia, triggers video extensions of footage that de Pencier shot on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, “that take you into another artistic reading of it.” Coral has been around for 45 million years yet could be extinct by the end of the 21st century – relatively speaking in the geological time scale, they add. Like the blink of an eye in VR goggles.

The exhibitions and documentary may introduce the general public to terms like anthroturbation (disturbance of sedimentary deposits by humans) and technofossils (human-made objects like plastic that are resistent to decay and will become future trace fossils). And a partnership with the Royal Canadian Geographical Society boasts an interactive website and educational program (theanthropocene.org). But above all they want the viewer’s response to Anthropocene to be visceral. “If we’ve succeeded,” de Pencier says, “it should be a more emotional than intellectual experience.”

“Especially in a secular society, there aren’t so many moments for that big reflection,” he adds. “That’s one of the hopes for the project: that people take a step back and think planetary scale and geologic time. And that there’s some shift, some reminder or recognition that comes from that perspective.”