To reach the Mickalene Thomas “Femmes Noires” exhibition on the Art Gallery of Ontario’s fifth floor, one must first cross a gallery of Old Masters and European art, past Rembrandts and a sculpture by August Rodin. The location is fitting, since the contemporary visual artist’s knowledge and subversion of that canon informs her realized works and disrupts western notions of beauty, identity and art.

With degrees from the Pratt Institute and the Yale School of Art, Thomas draws inspiration from images that have been canonized in the history of western art — iconic works from Balthus, Courbet, Warhol, Duchamp, Matisse and Manet. She then re-interprets them, usually by inserting the figures of black women who have been marginalized. “How she twists that is very, very important in her practice,” Julie Crooks, the AGO’s Assistant Curator of Photography, says. “Because she’s actually speaking back to them. Speaking back to this art history.”

The Thomas show comes at a time when art is rewriting and remixing the narrative and depictions of black women. One of the enduring viral moments of 2018, for example, is of two-year-old Parker Curry awestruck in front of Amy Sherald’s official portrait of the poised and powerful former First Lady Michelle Obama. That painting (and its counterpart, Kehinde Wiley’s official portrait of Barack Obama) unapologetically takes up space with both diversity and modernity to reframe the traditional art hierarchy, just as Thomas does in her collage-based oeuvre.

The work is of a piece with this cultural moment of remix culture that challenges accepted history — be it the photographs of Johannesburg-based photographer Zanele Muholi, whose theatrical self portraits reimagine black identity through the re-contextualization of symbolic poses and props, or Beyoncé incorporating audio samples of Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2012 Ted Talk “We Should All Be Feminists” into her performances.

Thomas has mined this material since her student days, Crooks explains: “I think she fits very neatly into all of these young African-American and African diasporic painters who are deeply interested in questions around race, representation, gender, and sexuality,” she points out as we tour the exhibit. “And now she is getting a lot of recognition for that work.”

When planning the “Femmes Noires” exhibition in partnership with the Contemporary Art Center in New Orleans, where it will travel after it closes in Toronto, Crooks wanted to distill the collage methodology and approach intrinsic to Thomas’s work. It was important, too, to highlight how the women Thomas depicts are a heterogeneous group: “There isn’t one note. It’s a range of black women, of black sisterhood.”

The journey in “Femme Noires” begins in a room surrounded on four sides by a portrait in the unique and instantly recognizable Thomas aesthetic, on that ARTnews once dubbed ‘rhinestone odalisques.” In each work Thomas composes images of women surrounded by a collage of vivid colours and textile patterns, their surfaces often encrusted with dazzling crystals. “I learned the hard way,” titled for a song by Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings Thomas was listening to as she painted, the subject is fierce. Her stance takes up space and is unapologetic, with an unwavering stare. “The title is so fitting. They are self-possessed black women,” Crooks points out, “and I think this kind of work can be transformative, especially for young black women in a society where they are constantly seen as other, marginalized and pushed to the periphery.”

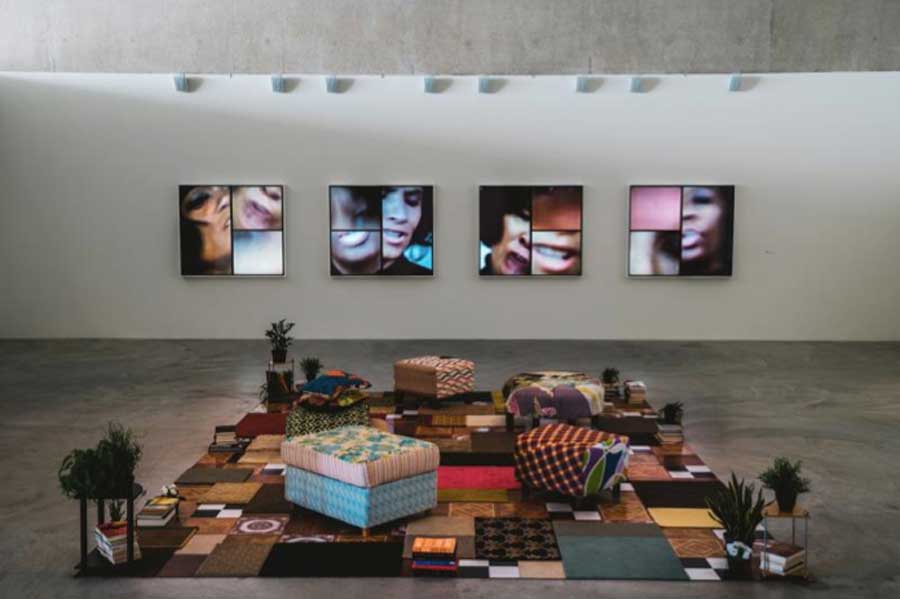

“Femmes Noires” is also autobiographical, and draws on Thomas’s experiences as a black queer woman. One series concerns the the film adaptation of Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Color Purple, which Thomas saw at the age of 13 with her mother, and its profound influence of seeing two black women kissing. Even the areas that invite viewers to spend more time contemplating the work are potent with personal and cultural history: The exhibition’s larger galleries include living room installations, for example, as sitting areas of patchwork carpet and parquet that harken back to Thomas’s 1970s childhood. The tableaux are dotted with furniture upholstered in batik textiles, plants, and stacks of books chosen by the artist — a mix of literary and non-fiction titles from Angela Davis and Maya Angelou to Ernest J. Gaines and Zora Neale Hurston that explore black women’s lived experience in the diaspora. (The AGO’s winter public programming, like a series of talks hosted by culture critic Donna Bailey Nurse featuring acclaimed authors like Esi Edugyan, M. NouerbeSe Philip and Angie Thomas, offer further explorations of “Femmes Noires” themes.)

The penultimate gallery is dominated by the video installation “Do I Look Like a Lady?” projected on a large wall. Individual cells of footage put comedians and performers in overlapping dialogue with one another on topics from sexuality and desire to defiance (like a clip of Millie Jackson’s “F*ck You” chorus). In this cacophony of projections, monologues from the likes of Wanda Sykes, Whoopi Goldbert and Moms Mabley are juxtaposed with Chakha Khan, Josephine Baker, Millie Jackson and Whitney Houston performances. They form a powerful commentary on the fragility of black celebrity even before viewers take in the complementary artworks around the room, ones that further explore black female identity, self-presentation and representations of glamour. “She’s always thinking about reflection,” Crooks explains. “Of who am I on screen, how am I reflected, what is that identity.”

Here, Thomas has silkscreened iconic images of Donyale Luna and Naomi Sims (the first black supermodels) or superstars like Diahann Carroll and Diana Ross on reflective acrylic, with slices of the image left bare so that viewers catch a glimpse of themselves in the art. “You are complicit,” Crooks adds, “and you have to confront yourself and you also have to confront these black women. And the story. It’s really complex, I think, in terms of identity and identity-formation and how black women throughout history, especially art history, have been outside of that conversation.”

The show’s final arresting image hangs alone: “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires” re-creates Edouard Manet’s then-controversial 1863 painting of a nude woman flanked by two dressed gentlemen — except here, Thomas offers a trio of stylishly dressed black women who meet the viewer’s gaze head-on, with self-assurance. It’s a strong statement that simultaneously critiques and appropriates French Impressionism, while also incorporating pop cultural references (1970s black action cinema costumes, the stylized constructions of fashion photography).

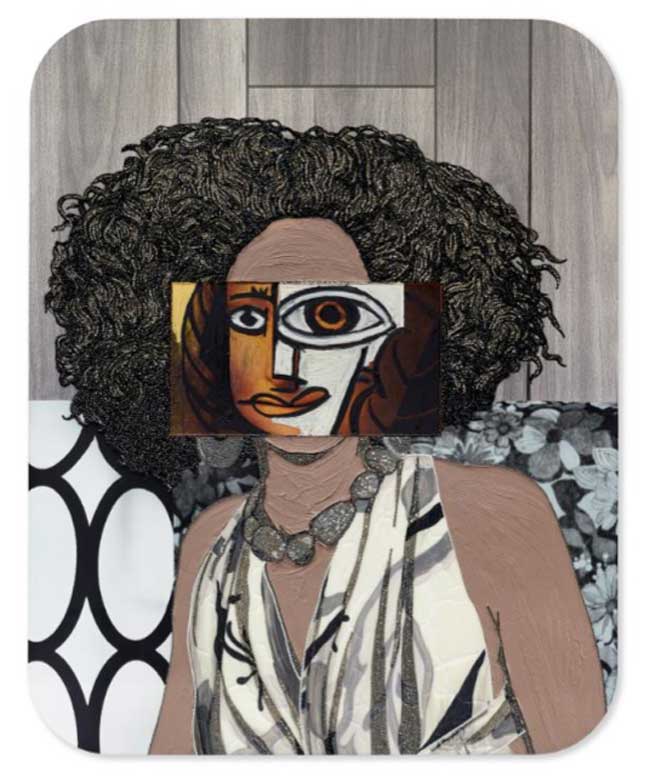

“The Western art historical moments that I am extracting as a source for my practice are not about reclaiming,” Thomas has said. That’s worth remembering when standing in front of this culminating work, and other paintings in the show like “Portrait of Kalena.” There, Thomas’s subject’s geometric collaged face is an explicit reference to the famous “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” by Pablo Picasso, whose visual experimentation was itself inspired by the wooden carved masks of African art. “It’s about acknowledging that the space was always ours, and about owning that space.”

Mickalene Thomas: Femmes Noires is at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto until March 24, 2019.