“It always seemed to me peculiar,” Moses Znaimer, founder and CEO of ZoomerMedia, muses as we stand among his celebrated collection of antique TV sets housed in the MZTV Museum of Television in Toronto. “We have the telephone, which is attributed to a single person — Alexander Graham Bell. We’ve got the airplane … attributed to two American brothers, but nobody knew anything about the people who invented TV. Not a single name was present in the culture. I thought that was outrageous.”

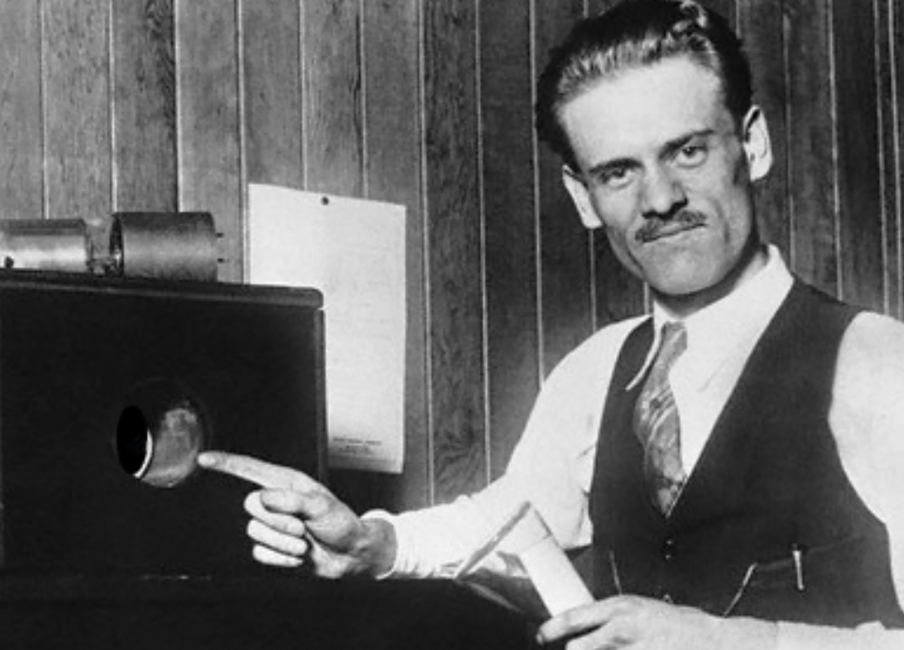

That’s partly why the names of some of television’s earliest innovators hang on the wall of the museum. Among them is Philo T. Farnsworth, born in Utah in 1906 and raised in a house with no electricity or indoor plumbing.

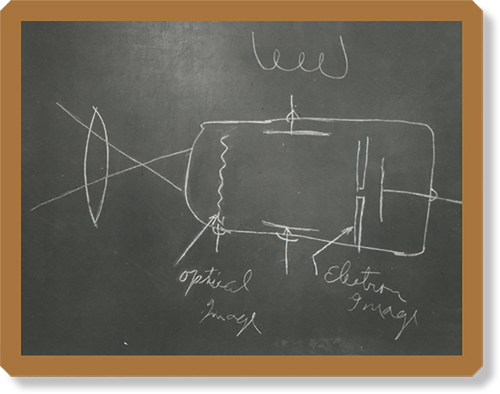

A voracious reader of science fiction magazines, Farnsworth actually conceived of the idea for electronic television while still only a teenager. While riding a horse-drawn plow through his father’s potato field, the crop lines it created inspired Farnsworth’s own concept for how rows of electrons could transmit images through the air. He shared diagrams of his idea with a high school teacher who encouraged him and, in 1927, at age 21, he transmitted his first image — a straight line. Electronic television, in its simplest form, was born.

Yet, in what technically qualifies as the first ever television plot twist, the years following Farnsworth’s innovation brought patent wars with the RCA Corporation and clashes with rival inventors, not to mention the Second World War, which put the development of television on ice. By the time the war ended, competitors nabbed Farnsworth’s expired television patents and continued the development of television technology themselves. Farnsworth himself, though vindicated by the eventual spread of the television technology he created, faded into the background of an industry he helped pioneer. The Emmys finally instituted the Philo T. Farnsworth Award in 2003, while Aaron Sorkin’s play The Farnsworth Invention, based on Philo’s life, ran for a three-month stint on Broadway beginning in December 2007, but Farnsworth’s name and work remains mired in virtual obscurity. Until now.

Beginning Saturday, Oct. 13, Forgotten Genius: The Boy Who Invented Electronic TV brings Farnsworth’s legacy to life through an interactive exhibit at the MZTV Museum of Television — fittingly situated among some of the oldest and rarest TVs in existence, including sets previously owned by Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley.

Curated by long-time television producer Phil Savenick, Forgotten Genius lays bare the story of Farnsworth’s life and television innovations, as well as the main players in his personal television drama — including his wife (and the first human ever captured on TV) Elma “Pem” Gardner. Remarkably, the exhibit also contains artifacts that date back to the conception of television itself, including a disc from the plow that Farnsworth was riding through his father’s potato field when his eureka moment hit, the first ever TV camera, created by Philo at age 19, the first electronic television camera tube, excerpts from the young pioneer’s journal and even Farnsworth’s own television set.

“We have one surviving disc from that harrow plow. It gets my jaw flapping — I don’t know about you. And then there’s the human drama because right by his side was his gal Elma. So this should be an epic movie,” Znaimer says, noting that Farnsworth deserves credit for his innovation in the way that Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, Microsoft founder Bill Gates and Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos receive. “Once you see the artifacts — the progression of crude science technology, the blown glass — to conceive that all of this was done by hand in a first example is kind of astonishing.”

Along with the television artifacts, visitors can also scan QR codes spread throughout the exhibit to watch unique clips related to Farnsworth’s life, including the one and only time Philo himself appeared on television — as a guest on a 1957 episode of the game show I’ve Got A Secret.

Yet another pivotal television moment in Farnsworth’s life occurred 12 years after that, on July 21, 1969, when Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon. The giant leap for mankind was broadcast back to Earth via the television technology Farnsworth created and as the pioneer himself watched the historic event he reportedly told his wife that, while he wasn’t sure if all of his struggles, and all the money he lost out on, had been worth it, at that moment he knew that it was.

“We have more technology in this [smartphone] now than they had going for the moon shot,” Znaimer notes, a nod to Farnsworth’s ongoing legacy. “We live in a universe of screens and every screen that is currently extant owes its situation to the original screen.

“And so, now we’re trying not to resuscitate the fortune which never was, but just his reputation,” he adds. “He deserves to live forever.”

Forgotten Genius: The Boy Who Invented Electronic TV opens on Saturday, October 13 at the MZTV Museum of Television. Click here for more information.