Long Live the Queen: What Her Majesty Can Teach Us About Aging

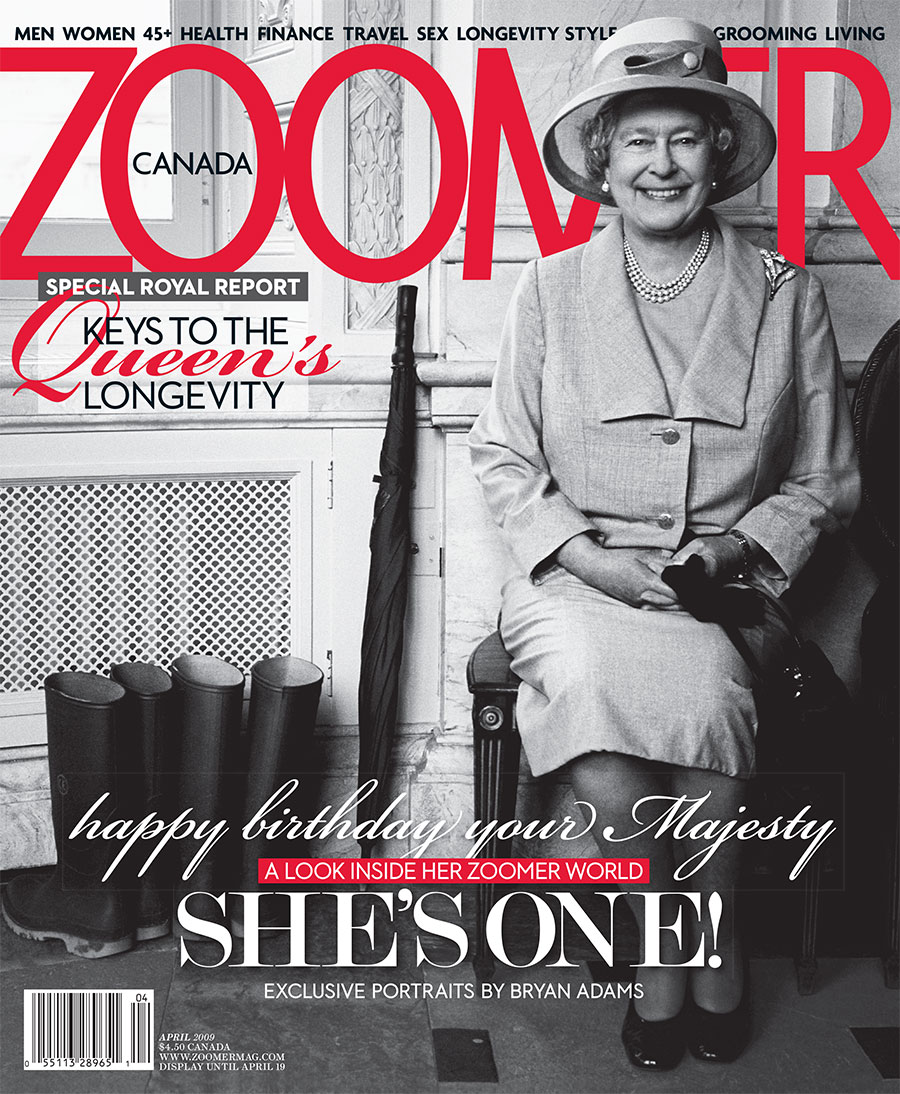

Photo: Bryan Adams

If you’re ever in a room with the Queen, you will notice that she exerts the same gravitational pull as a celestial body — a star, let’s say. A small, sturdy star in dignified shoes and ancient diamonds, with a hairdo as unchanging as the heavens and a smile that is rare and dazzling. People who are normally quite sane become teenagers in her presence, craning to get a look while trying desperately to appear indifferent. They are drawn to her like metal shavings to a magnet, and their conversation invariably runs along well-worn lines: “Oh, isn’t she lovely? Look at that skin. She’s so tiny!”

I know this because I met the Queen once, in the spring of 2005, and have been in her presence on three other occasions — four, if you count the time that I, age six, allegedly crawled through the crowd at one of the sovereign’s Toronto appearances and screamed to my parents, “She’s got a run in her stocking!” I don’t actually remember that, although it’s written in The Big Book of Family Myths, Renzetti Edition, Vol. 1.

I do remember standing in one of Buckingham Palace’s cavernous red drawing rooms, with giant van Dycks and Titians staring down from the walls. It was a reception for Canadians living in London, and the invitation had come from a mysterious person called the Master of the Household. With that title, it seemed best not to cross him, so at the appointed time, we arrived and presented our engraved invitation to the policemen at the gate, while the tourists outside didn’t even attempt to hide their scorn. “My God,” they were clearly thinking, “they’ll let any old hobo into the palace these days.”

The party was, in many ways, classically English: almost no food and enough alcohol to stun the Russian army. The Queen’s legendary frugality was evident in the scant plates of Doritos placed on priceless side tables. The Canadians milled about, politely, hesitantly, wondering about protocol. Should you make small talk with the Queen when presented to her, perhaps about football or the perils of public transit? Was it necessary to curtsy?

“If you don’t,” whispered one of the footmen, “she won’t send you to the Tower.” Then I was before her, and she held out a black-gloved hand. In the moment it took for her to say, “How do you do” (you could cut cheese on those vowels), I noted that the idle chitchat was all true. She is small — only five foot three — and bright-eyed, with hair that defied the laws of nature, and skin that I would have sold my soul for when I was 25. She had just turned 79.

This is from 1948: “Quite mysteriously, a visit by a young princess with beautiful blue eyes and a superb natural complexion brought gleams of radiant sunshine into the dingiest streets of the dreariest cities.” Her private secretary, Jock Colville, was describing the effect of the 22-year-old Elizabeth during a tour of Britain, which was still reeling from the war. With her was her new husband, Prince Philip. In Gyles Brandreth’s biography of the couple, there is a lovely anecdote about their early years: when Philip’s cousin remarked on the princess’s beautiful skin, her husband laughed and said, “Yes, and she’s like that all over.”

That skin. You really can’t buy it anywhere, and you certainly won’t find it at a doctor’s office, no matter how much pulling and peeling is on offer. It’s one of the reasons English women age so well. They may complain about the endless rain, the clouds that hang over the country like wet laundry on a line, but that climate is the equivalent of having an expensive humidifier running 24 hours a day.

I once fell to talking with an elderly woman on the bus in London. She had a cart full of groceries, because, at 89, she was doing what she did every week: her shopping, as well as her daughter’s. There were a few lines on her lily-petal skin but not many. I commented on how well she looked. “Oh, but I’m tired, love,” she said, with a wide smile. “I’m ready for the Lord to take me.”

Well played, madam. In a sentence, the bus lady had summarized all my theories about why British women are often so handsome and hearty far into their later years. They walk everywhere, maintain a sense of humour and, above all, adhere to the adage that served them well in the war and beyond: “Mustn’t grumble.”

Last summer, it was impossible to avoid the pictures of a beautiful blond woman on a beach in Italy, her hand to her eyes, dressed in a red bikini. She was not young, but she was spectacular. The picture was so popular, in fact, that the bikini’s manufacturer could not keep the bikini in stock. The woman was British actress Helen Mirren, who, at 62, was two years past her country’s statutory retirement age for women. Famously, Mirren had won an Oscar for playing the Queen, although no one who looked at that bikini thought of wet corgis and drafty Scottish castles.

No, they thought, “Six decades along, and she still has something to teach a bikini.” She also has something to teach her North American sisters about growing old gracefully. Her face remains recognizably her own, and not the product of a plastic surgeon’s creativity. A month after the famous bikini shot — which Mirren attributed to a fluke of the light — she told a British magazine, “I’ve never had any work done — women in Hollywood don’t look young when they have all that work done. They just look odd.”

In her words, you hear an entire culture that is still suspicious of cosmetic renewal: especially for women of a certain age and mindset, it is just too vulgar, too common. Too American. When I interviewed actress Emma Thompson, a few months shy of her 50th birthday, she fixed me with a mock scowl and said, “I’m not fiddling about with myself.” I didn’t think she had been; she looked too good. When I met Vanessa Redgrave, what I noticed was her extraordinary bones; with Vivienne Westwood, it was her wonderful Yorkshire accent and milky skin. Westwood was wearing tiny gold horns on her head; she was batty; she was magnificent. I did not look at them, as I have so many American celebrities, and think: “How did you end up looking like a peeled grape?”

It’s not that cosmetic surgery is unheard of in Britain (in fact, surgical procedures rose by 12 per cent in 2007 over the preceding year); it’s just that most women, as they say here, can’t be arsed. They’d rather have a drink or a laugh or a roll in the hay, which is useful in understanding another example of mature English womanhood, the Duchess of Cornwall. Explaining Camilla’s earthy charms, her biographer, Caroline Graham, told me: “She probably doesn’t even know what Botox is. She certainly doesn’t go to the gym. Her exercise is walking the dogs, riding. She enjoys eating. She enjoys her gin and tonic at the end of the day.”

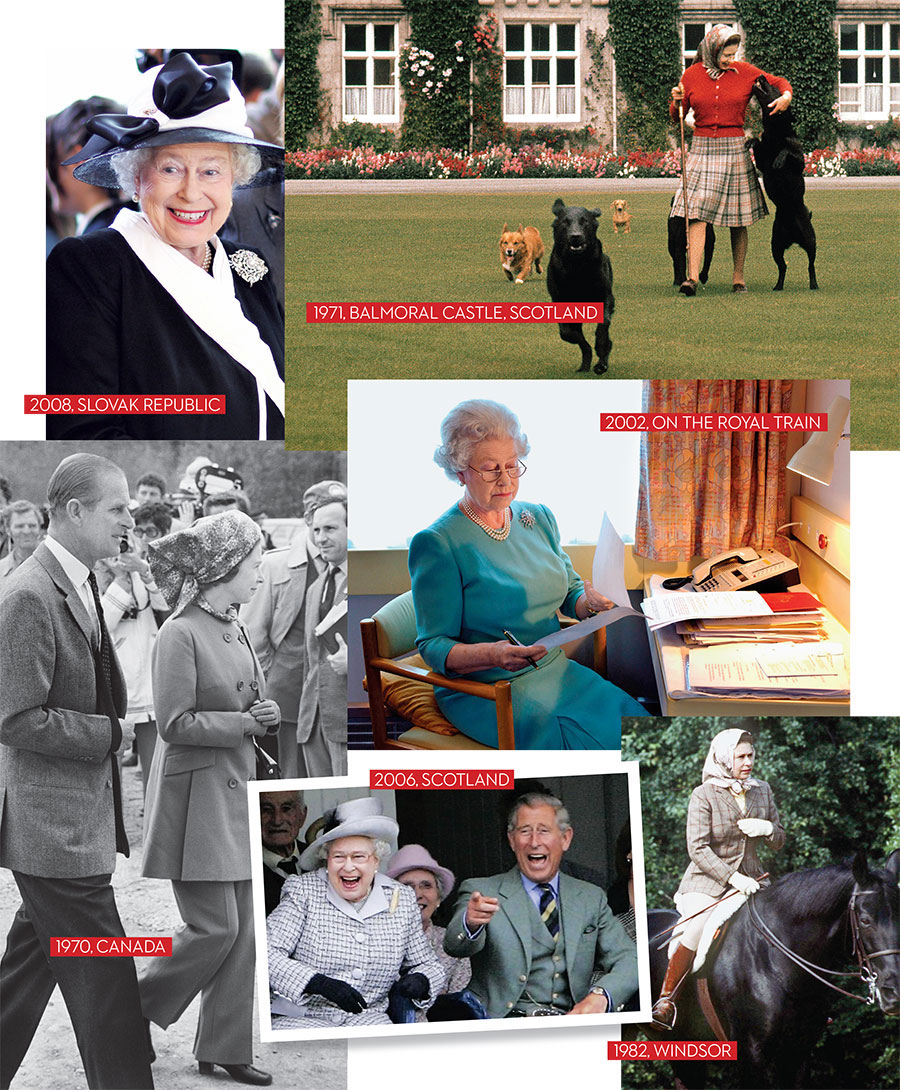

No wonder she’s slipped into the Windsor family without effort. The Queen Mother, Prince Charles’ grandmother, also famously loved a gin and tonic at the end of the day. She was 101 when she died, and she was on public display, waving and beaming, until the end. Her daughter, the Queen, has ruled since 1952, making her the second-longest reigning monarch in British history, after Queen Victoria. The women in that family are built for marathons, not sprints. The current monarch keeps her body fit by riding her horses and walking her dogs, and her mind keen through diligent examination of the events affecting her country. Every afternoon, she is brought a “red box” of documents on everything from government legislation to news about who’s getting knighted that year.

It is a little-known fact that the Queen is a bit of a policy wonk. Although her diary is not as full as it once was, her commitment to the job is unswerving; she still carries out hundreds of royal duties a year, from state banquets to hospital visits to foreign tours (in Jamaica, one of the 16 countries of which she is head of state, she’s known as “Mrs. Queen”). Among the highlights of the royal calendar — at least for the cake-hungry commoner — are the Queen’s garden parties. She holds several a year, at least three at Buckingham Palace and one in Scotland, and it was in her London backyard that I encountered her for the second time.

There wasn’t an opportunity for a “how do you do,” but I watched her as she parted the crowd in her lavender suit and electric-blue hat, so bright against the green of the lawn. The party-goers in Prince Philip’s path blithely abandoned him and went loping after the Queen, hoping for a word or smile.

A young couple stood clutching each other in the middle of the crowd. Judith Cousins-Woodrow and her husband, Mark, a pair of accountants from Scunthorpe in northeastern England, were so giddy, you just knew they’d met the Queen. They had indeed been chosen by one of the palace’s advance men, who likes to shake it up and give her a nice mix of folks to talk to — young, old, men, women, the dignified bishop and the accountant about to keel over with excitement. For Judith, who had never expected to be invited to a royal garden party, let alone meet royalty, it was an afternoon for the ages. She was surprised at how well the Queen looked. “When she smiles,” Judith sighed, “her whole face lights up.”

A version this article originally appeared in the April 2009 issue.

RELATED:

The Future of the British Monarchy as Elizabeth Prepares to Mark 70 Years as Queen