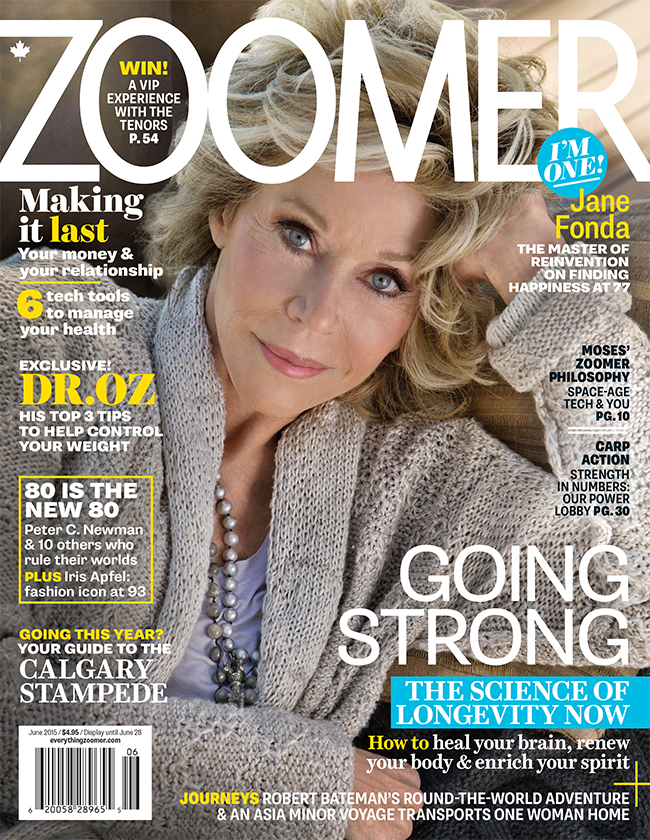

“My Life Is Like An Experiment” — Jane Fonda On Adapting and Learning Later In Life

Jane Fonda chats with Zoomer about her evolution as an actor, her activism and aging. Photo: Tony Duran

Hollywood royalty, political activist and cultural touchstone, Jane Fonda is a woman of her times.

There’s a fairy-tale evolution in the life of a Hollywood actress that’s supposed to go something like this: ingenue, fashion model, serious actress, celebrity sensation, Oscar winner, screen legend.

Over the course of an epic career, Jane Fonda has filled all those roles, and many more, with a restless spirit that suggests none of them has ever been enough for her.

She’s always been the woman on the verge of breaking out of whatever part she’s playing, both onscreen and off. And her roles have mirrored the cultural and political landscape with uncanny synchronicity.

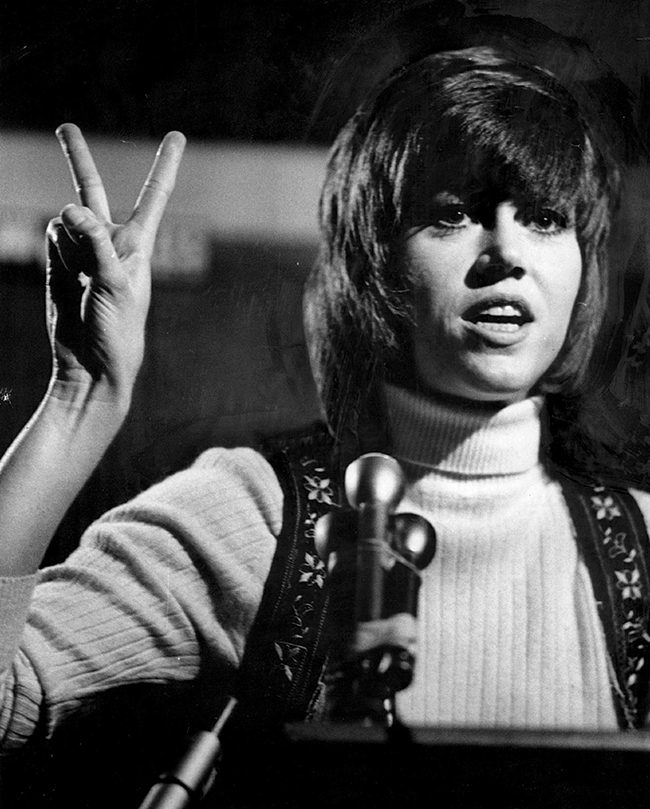

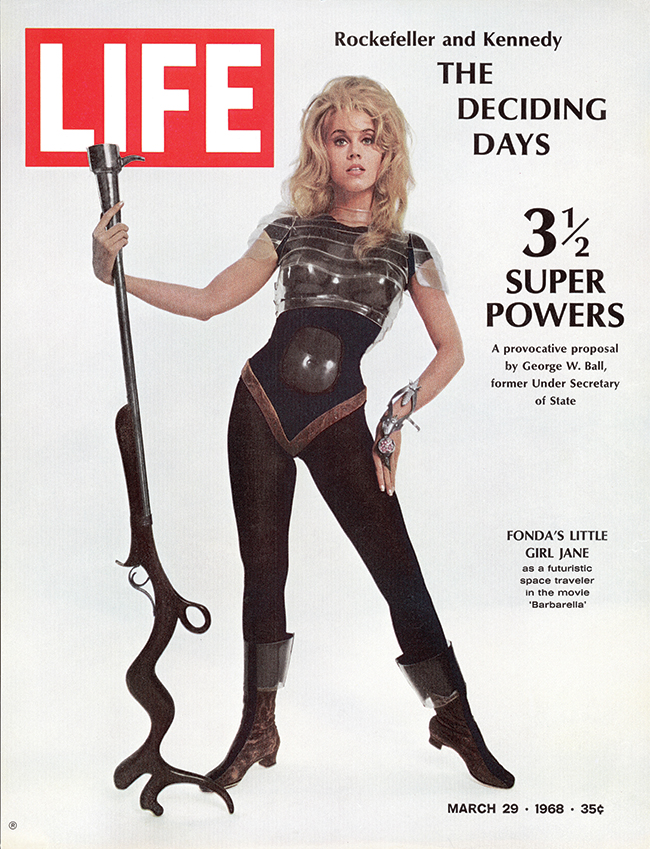

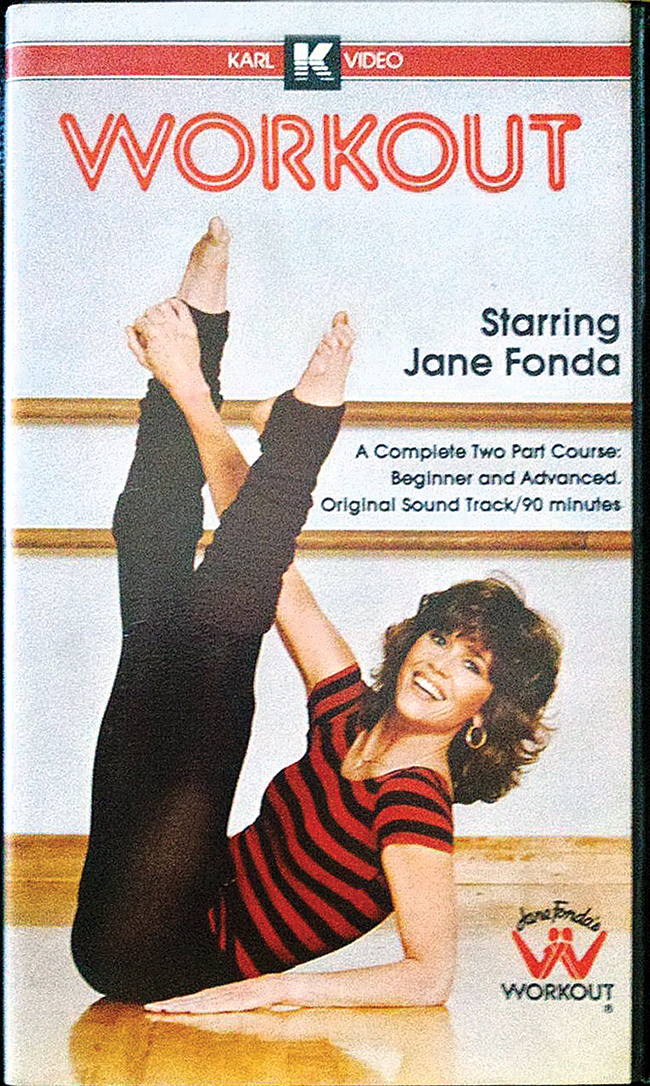

In the swinging ’60s, she was Barbarella, a sci-fi sex bomb wired to the French New Wave. In the ’70s, she was Hanoi Jane, branded a traitor for posing on an enemy anti-aircraft gun during the Vietnam War – she would later apologize for the photo op but not for the politics. In the ’80s, she morphed from bulimic activist to feminist fitness guru. And in the ’90s, with a head-snapping right turn, she quit acting to become trophy wife to media mogul Ted Turner.

It’s no wonder that when she asked her daughter, Vanessa Vadim, to help make a short film about her life for her 60th birthday, Vanessa said, only half joking, “Why don’t you just get a chameleon to crawl across the screen?”

Over the years, a kaleidoscope of causes made her a moving target for the FBI and the CIA, including her embrace of the Black Panthers, American war veterans, radical feminists, foes of nuclear power, gay marriage and abused women. For much of her career, Fonda has served as the canary in the coalmine of American pop culture and politics.

Her three divorced husbands, meanwhile, could have been cast as serial symbols of the Zeitgeist – playboy filmmaker Roger Vadim for the age of free love, leftie politico Tom Hayden for the age of dissent, Turner for the age of money. Now, she’s happily unmarried.

In the 21st century, Fonda is still shape-shifting (without ever, god forbid, getting fat). Having resumed her acting career in 2015 after a 15-year hiatus (which must be a record for star of her stature), she has embraced her third act like a 77-year-old comeback kid, reinventing herself on the front lines of the TV revolution.

In HBO’s The Newsroom, she upstaged everyone as steely media mogul Leona Lansing (a distaff twist on Ted Turner). And now in Grace and Frankie, a Netflix series that premiered this spring, Fonda reunites with Nine to Five co-star Lily Tomlin in a situation dramedy about two women whose husbands (Martin Sheen and Sam Waterston) declare they are gay – and are ending their 40-year marriages to be with each other.

But no matter how many great roles have come and gone, the Barbarella space kitten from Vadim’s film of the same name is the one tag that still sticks to Fonda. Even though it’s a sexist stereotype she’s spent her life trying to erase, Fonda has attacked her roles and causes like a ninja action figure, both serious and sexy, while tracing a character arc worthy of a biopic. And now this prodigal daughter of Hollywood royalty – who lost her mother to suicide at 12 and felt spurned by cold father (screen icon Henry Fonda) – has come full circle.

At 77, confident and poised, she is the most elegant star of her generation. And like an elder Angelina Jolie, she continues to wield her celebrity with a larger-than-life social conscience. These days, she spends her spare time serving as a mentor to young female victims of sexual abuse. As she is quick to point out, the one thing about her that hasn’t changed since the ’60s is that activism still matters to her at least as much as acting.

“I think I became a better actor because of my activism,” she told me in a recent interview. “When you’re an activist and you’re trying to end a war or you’re trying to make things better for women and girls, you’re not going to spend a whole lot of time wearing a designer outfit. I spent 20 years not even wearing makeup and not looking so great, frankly. I mean, it’s ironic that it’s in my late 60s and 70s that I look kind of glamorous because I never did before.”

It’s not the first time I’ve met Fonda. We talked in 1989 when she was promoting The Old Gringo with Gregory Peck, and she struck me as a nervous wreck. It’s always weird when the celebrity is more anxious than the journalist. But I wasn’t aware at the time that she was reeling from the breakup of her 17-year marriage to Hayden (the father of her son, Troy) and poised to quit the film business. The Jane I met on the set of Grace and Frankie was a radically different woman.

The show is filmed on the lot of Paramount Pictures, the only major studio that still occupies a piece of Hollywood real estate. As the security guard waves my rental car through the classic arches, it’s like entering a time warp. Everything is still painted the same sandy beige – the hangar-like stages, the bungalow offices, the totemic water tower looming over the compound, which looks like a fake set of a retro studio lot. Home to countless movies and TV shows for the past 75 years, Paramount seems an odd place to be shooting Grace and Frankie, which is neither a movie nor a TV show in the traditional sense but a series created by Netflix, the outfit bent on making the world of entertainment as we know it obsolete.

I wait for Fonda in a conference room next to Stage 23. When she breezes in with Lily Tomlin, I almost don’t recognize her. She’s tricked out like a superannuated punk in spike heels, ripped blue jeans and a dark indigo tee, a blue streak running through her hair, which is teased into a scary tangle.

Her makeup is stark and heavy. Tomlin strikes an equally incongruous though less bohemian pose, dressed like a grand dame in a creamy pink designer jacket, black pants and silk scarf, her hair sculpted into a French twist. She seems faintly embarrassed to look like she just stepped out of Beetlejuice.

“Our characters don’t usually look like this,” she says. “We’re in costume.” The familiar voice, throaty and declamatory, sounds like it could move large objects out of the way.

Fonda is tiny and severely thin, which comes as a shock after seeing her cut such a swath through The Newsroom as the imperious Leona Lansing. Pulling a chair away from the table, she plunks herself down, grabs another chair and props her legs out straight. As we talk, she’s constantly stretching, as if her wiry frame, tuned by decades of ballet classes, is a yogic entity with a mind of its own.

While Tomlin is a comedy legend, Fonda is the bigger star, and she fills the room with a crackling energy and a forthright manner. Describing the episode they’re currently shooting, she says, “It’s toward the end of the season, and we’ve decided to go out on a ‘say yes’ night. You can’t say no to anything. So I’m wearing her, and she’s wearing me.”

Grace (Fonda) and Frankie (Tomlin) are polar opposites, two frenemies thrown together by their husbands’ decision to come out of the closet and become a gay couple. “My character is a hippie kind of earth-motherish woman,” Tomlin explains. Fonda, on the other hand, plays a straight-laced conservative helpmate who teaches Sunday school. “She’s used to pleasing,” says Jane, “twists herself into shapes to please the man. She’s never really said, ‘No, this is who I am and I’m going to do what I can to please myself.’ ”

Can she relate to that? Fonda doesn’t miss a beat: “Like, most of my life.” That changed at 62, she says, “because I was finally single. When I became single, I could say, ‘Wait a minute!’ ” Fonda has not remarried but has a boyfriend – Richard Perry, a 72-year-old music producer who has made records with acts ranging from Fats Domino and Tiny Tim to Rod Stewart and the Pointer Sisters. Perry has Parkinson’s disease, and last year Fonda publically threatened to leave him if he didn’t take his treatment more seriously. “It’s hard,” she says. “It’s hard on him and it’s hard on me.”

Fonda’s 2005 memoir, My Life So Far, conveys a sense of unabashed affection for the men in her life. No matter how much feminist eye-rolling she brings to her tales of Vadim’s doctrinaire promiscuity or Hayden’s professional jealousy or Turner’s perverse mispronunciation of “monogamous” as “magnanimous,” a forgiving love for all of them shines through. When asked about romance with Perry, she says, “We’ve only been together five years. People who have been together for long, long periods of time have told me, and I have seen it, that it really gets better, that it can get so beautiful. That’s the one thing I’m jealous of. I will never know that.”

When Fonda talks about aging, however, she is militantly upbeat: “I know people who have life-threatening diseases, who know they’re dying but have a sense of enormous freedom. There’s a capacity for happiness and well-being as you get older that simply doesn’t exist when you’re younger because there are so many pressures.”

While she comes across as a preternaturally youthful force of nature, Fonda is the first to cop to her own mortality. The body that has earned a fortune in those blockbuster workout tapes is ravaged by her battle with bulimia, the eating disorder that endured into her 40s and left her bones fragile and prone to fractures. “My body hurts,” she says. “It’s not that I don’t physically feel my age. I have osteoarthritis, I have a fake hip, a fake knee, a fake thumb, blah, blah, blah, blah. The challenge is not to let that define you. I am not a hip replacement. I am a healthy person who walks an hour a day, meditates an hour a day when I can, sleeps nine hours a day. Sleep is the most important thing for me.”

She sleeps nine hours a day?? After countless celebrity interviews, I’ve become immune to coveting their fame or wealth. But sleep? That’s an enviable talent.

Not that Fonda is snoozing her life away. She’s fuelled by work. “I don’t feel a need to keep working,” she says. “It’s what I want to do. I have a tremendous amount of energy and so many ideas. The main thing that keeps me young is that I’m a perpetual student. My life is like an experiment. I’m constantly learning and growing and hopefully deepening. Retirement – I don’t even know what that means.”

As death creeps closer, it only seems to stiffen her resolve. “Hitting 70, it’s one thing – 77 is closer to 80, and it all gets more serious, meaning there’s a whole lot less time ahead of me than behind me. So what I do with it, how I choose to grow as a person becomes really important.”

And sex? “Well, I used to think it was important until I sort of don’t have it as much right now. It’s hard to have sex and do a TV series.”

Tomlin laughs. “I think it’s as important as you make it,” she offers.

Friends since the ’70s, Fonda and Tomlin are clearly comfortable with each other. “I got the idea of doing Nine to Five as a comedy because I saw her one-woman show,” says Fonda. “ I said I’m not going to do a movie about secretaries unless Lily Tomlin is part of it.”

But Tomlin is not just a comedienne. In Grace and Frankie, she more than holds her own as an actor. When I ask if she could swap roles with Jane, she says, “I’m one of those actors who think I could play anything. Like Alec Guinness.”

You sense she’s only half joking.

In casting Grace and Frankie, writer-producer Marta Kauffman (co-creator of Friends) “didn’t think about anyone else than us,” says Fonda, who is chuffed to be playing her first lead in a TV series. “People ask me to do more theatre,” she says, “but you have to be rich to go to the theatre. I want to do something that a lot of people see and has a cultural impact. It’s about audience and a steady job. I love having a steady job. I’ve never worked for four months in my life. I came up in an era where, if you were a movie star, you would never do television.”

When Fonda was at the peak of her film career, movies were not only more prestigious than TV but more relevant. Though she was a child of Hollywood, it’s worth remembering that her career was incubated in France, where she spent six years. There, politics, sex and cinema formed an inseparable ménage à trois. And she rose to stardom with a generation of American directors inspired by the French New Wave.

Rebounding from the pre-feminist folly of Barbarella (1968), she scored her first Oscar nomination as the star of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), a Depression-era drama about a brutal dance marathon that lays bare the despair behind the American Dream.

She then won the Oscar for playing a prostitute in Klute (1971), a role enriched not just by researching the sisterhood of the street but by the morning-after tête-à-têtes she once enjoyed with the Parisian call girls that Vadim would recruit for threesomes in their marriage bed.

In 1979, Fonda won her second Oscar for Coming Home, which grew directly out of her work with disabled Vietnam vets. The same year, The China Syndrome, her cautionary thriller about nuclear power, seemed an extension of her own anti-nuclear campaigning. And just two weeks after the movie opened, a catastrophic leak at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island reactor turned it into a blockbuster.

Even on the personal front, Fonda made her movies matter. In 1981, she used On Golden Pond to engineer an 11th-hour rapprochement with her ailing father, who was cast as her emotionally stunted dad, while Katherine Hepburn played her mother. Just months before his death, Henry Fonda finally won the Oscar that had eluded him all his life, while Hepburn bagged her fourth. The film’s poignant drama about a dying patriarch topped the box office that year – now hard to imagine in a world where virtually every blockbuster is a cog in a comic-book franchise.

Fonda still ranks On Golden Pond among her most treasured films. She also singles out Hepburn as a critical influence. “She was difficult and prickly and extremely jealous and competitive but she was the perfect elder. She taught me the importance of failure, that you learn more through it than through success. And she taught me the importance of standing up to your fears and being self-aware. “

Applying the kind of dedication she once reserved for politics, in My Life So Far, Fonda audits her past with a writerly self-awareness while letting affirmation trump regret. Even now she swears that her 15-year break from acting was not time wasted. “Ten of those years were spent with Ted Turner,” she tells me. “I don’t regret that. And for five years, I was writing my memoirs, which I don’t regret either. I was very unhappy at the time I decided to leave the profession. During the years with Ted, we’d watch TV and go to movies and never once did I think, ‘Oh, my god, I wish I had done that [role].’ I never imagined I would go back. When I came back, I was a really different person, a better person.”

Fonda continues to land film roles. She next co-stars with Michael Caine, Rachel Weiz, Harvey Keitel and Paul Dano in The Early Years, the English-language debut by Italian director Paul Sorrentino (The Great Beauty). Asked what other directors are on her bucket list, she says, “They’re all dead.” Then she quickly amends that to say she’d like do another film with Sorrentino and rhymes off auteurs honoured at this year’s Oscars – Birdman’s Alejandro Iñárritu, Boyhood’s Richard Linklater and The Grand Budapest Hotel’s Wes Anderson.

But unlike other actors who bring such intention to their work, Fonda says she has no desire to direct. “There’s too much work in being a director. I’m just too much of a loner. The day is over, and I go home. I have my martini and, you know, just do life. If for some reason I can’t act anymore, I would write.”

So what’s best thing about getting old? “Wisdom,” she says, with no hesitation. If an unexamined life is not worth living, as Socrates once advised, Jane Fonda makes the examined life look like her best role yet.

A version of this article appeared in the June 2015 issue with the headline, “Attitude,” p. 55.

RELATED:

Forget Counting Sheep! Jane Fonda Says a Puff of CBD Is All She Needs for a Good Night’s Sleep