The Self-Driving Car: Going Hands-Free

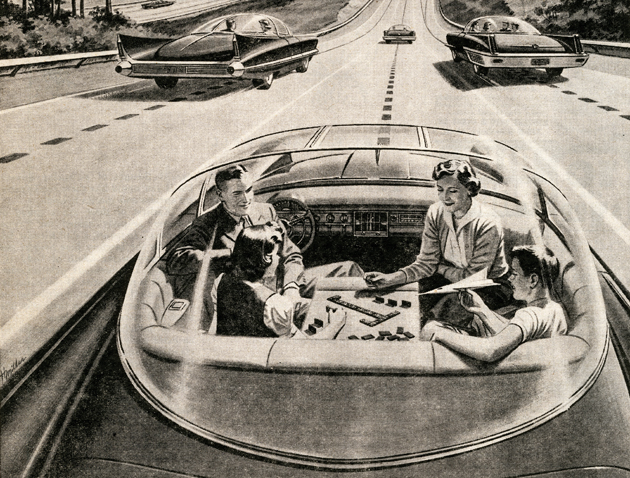

Autonomous driving technology – the self-driving car – is a hot topic lately and not just among techies and motor heads. That’s because, as cartoonish as it may seem, it’s not that far off.

Driving standard on the hilly streets of San Francisco is ill-advised if you’re a novice, but that’s the kind of thing you do at 23. It was my best friend’s VW Bug, it was summer and it was nothing but fun. Fast forward a few decades to last June, and I’m in San Francisco once again, having déjà vu.

This time around, I’m driving along the Embarcadero heading toward the Golden Gate Bridge in a Mustang the colour of Campari on the rocks – a different ride, equally fun. The question though is this: would it be as much fun if the car was driving itself?

Autonomous driving technology – the self-driving car – is a hot topic lately and not just among techies and motor heads. That’s because, as cartoonish as it may seem, it’s not that far off. Even if you’re only vaguely aware of how a vehicle actually works, you do know that technology evolves at warp speed. Everything is on a two- to three-year upgrade cycle: phones, computers, media players. Cars are overdue.

The lead-up is a bit of a tease though. Today, we drive cars that are computerized, Bluetoothed, GPSed. We take this in stride, not focusing on what’s next. These features are called “driver assist.” It’s entry-level, the gateway technology that makes the fully driverless car slightly less impossible to imagine. Beyond cruise control, this includes lane departure and forward collision warnings, blind spot detection and rain-sensing wipers. Driver-assisted technology is marketed as your co-pilot, a second set of eyes, courtesy of electronic sensors, tiny cameras and magical algorithms that you’ll never see.

I tested Ford’s latest autonomous parking feature while in San Francisco and I could clearly see the benefits. Counter-intuitive as it seems, relinquishing control of the steering wheel and letting the car park itself could be, at the minimum, a relief. It negates the need to crane around – a gift for less flexible drivers like my parents who are already dedicated to the security of the backup camera. Similarly, if the vehicle can get in and out of tight parking spots on its own, you’re not only safer, you avoid your share of parking dents.

Semi-autonomous technology is what is in our immediate future: features that will give the car permission to take control of the steering, throttle or brakes without your direct involvement – basically, to keep you out of trouble. This includes course-correction if you drift out of your lane and braking on your behalf when a collision is imminent. Last year in Europe, Ford released a car that will keep you to the speed limit. This can’t be popular on the Autobahn.

Eventually, cars will drive themselves if lawmakers and insurance companies can accommodate them. Ford and the other legacy automakers are feverishly working to advance their proprietary technologies from research to engineering to make this a reality. When that day comes, it will be a defining moment for them in their quest for reinvention as climate-conscious-forward thinkers – a necessity now that technology companies have entered the race.

Google is aggressively developing its own driverless car, promising to deliver it within five years. So is Apple, says Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, who told BBC News it was an “open secret.” He also said that in future owning a conventional non-self-driving car will be “like owning a horse.” Ford, on the other hand, is taking a studied approach, projecting that within five years a fully autonomous vehicle could operate in controlled situations – meaning somewhere it doesn’t rain. Sensors don’t like rain.

In fact, our entire approach to mobility is morphing – Uber has made that plain. The app-based global ride-sharing network is a juggernaut that has turned ye olde taxi culture on its head. Meanwhile, earlier this year, Detroit stalwart General Motors announced a $500 million investment in, Lyft, a ride-share service that competes with Uber. Together, the automaker and the tech company plan to develop an on-demand network of self-driving cars. While it’s not an obvious partnership, GM and Lyft say they are united in the view that consumers will experience self-driving cars first through ride sharing, rather than through individual ownership.

There’s a reason that the self-driving car is so compelling to us. Our relationship with automobiles has evolved dramatically over the past 50 years. The conversation used to be about horsepower; now it’s more likely about fuel consumption. What was always a status symbol and a ticket to freedom for boomers is self-indulgence to millennials – and a climate faux pas. Automation in driving will represent a radical change in how we get around, but also in how we see ourselves.

I wouldn’t have connected the dots between the self-driving car and Herbie the Love Bug if I hadn’t heard Genevieve Bell speak at the Further with Ford conference last spring in Silicon Valley. A cultural anthropologist and VP at Intel, Bell talked about our long-standing fascination with automation and how it manifests itself in literature and film. From Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to cars coming to life in popular films like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and The Love Bug, we have “persistent fantasies … recurring anxieties about evolving technology,” she says.

The universal promise of automation is to make us safer on the roads and give us back the time we lose in traffic and commuting. Technology zealots like Internet entrepreneur Reid Hoffman go further, saying it will improve society across the board. Hoffman, the co-founder of LinkedIn, posted an essay detailing the pluses: “safer, faster, more energy-efficient, economical and fun.” Since more than 90 per cent of accidents are caused by human error, he argues, removing the driver will reduce the number of collisions. And self-driving cars will not “curtail personal freedom – they’ll amplify it,” he says, citing their value to people with limited mobility: “senior citizens, people with disabilities, young people.”

Practicalities aside though, I wonder whether anything could replace the visceral kick one gets cruising along in a Mustang or riding high in the F-150 pickup truck, so commanding and cool. I’d say it’s going to be a long trip getting from Drive to Ride.