What Robert Wiener, Formerly Canada’s Oldest Man, Can Teach Us About Superlongevity

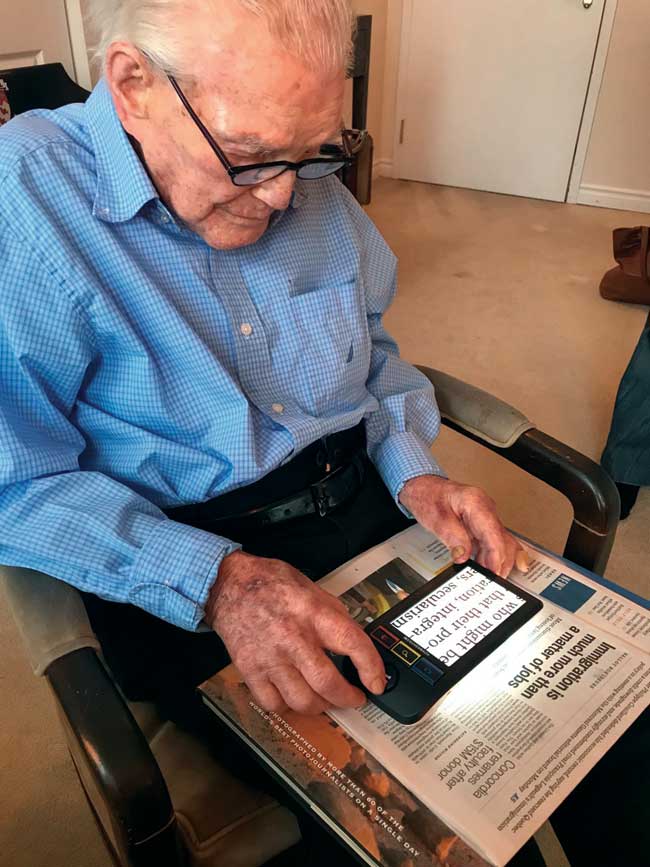

Robert Weiner circa 2015. (Photos: Courtesy Wiener Family; Allen McInnis/Montreal Gazette)

The following article was written before Robert Wiener passed away on Feb. 17, 2019 at the age of 110.

Celebrating Dr. Robert Wiener’s birthday is always tricky. Because it falls on the same day as the death of his beloved daughter Lois, he often prefers to forget the day as it rolls by.

But 2018 was a Big One; there had to be a party. There was talk of going out to Nick’s for burgers, but Dr. Wiener—“Bob” to his friends—said he’d prefer to stay inside the seniors residence in the Montreal borough of Westmount. The little library was set aside for the family to muster in. Wiener has outlived all his siblings, but sons Ken and Neil would be there, and cousin Harvey and niece Shoshana were flying in from Florida and Halifax. It was a bit of a to-do.

So Wiener would have to front-load his day. After a 9 a.m. rise and a quick breakfast, he snapped into exercise mode: stretching, leg-raises, sit-ups and then into his workout shirt for 30 minutes on the stationary bicycle. Then it was time to get spruced up; a retired dental surgeon with a Kirk Douglas bearing, he is as meticulous about his presentation as he is about everything else. He even wore a suit for the occasion—something modesty usually forbids. As the party approached, it became clear he might not get his Montreal Gazette read that day.

Last June 19, Wiener quietly overtook Zoltan Sarosy, a Hungarian-born chess master who lived in Toronto, to become Canada’s oldest man and its 40th documented supercentenarian. (A supercentenarian is a person who has reached 110 years of age.)

Extreme longevity is a domain that women overwhelmingly dominate. On the list of the oldest people alive, topped by 115-year-old Kane Tanaka of Japan, you don’t hit a man till No. 16; of the 35 oldest living humans, 33 are women.

And so among men, Wiener finds himself in rarer company still. Roughly the same number of men have orbited the moon (24) as are older than Robert Wiener is right now.

As his father approached age 110, his son Ken, a 68-year-old retired corporate lawyer, logged on to a popular Web forum called The 110 Club—a watering hole for “citizen gerontologists.” These are extreme-aging enthusiasts whose reverence for elders harkens back to a time when the oldest among us were deemed wise and holy and somehow too important to die until the lessons of their life were absorbed by the tribe. Ken typed in a message announcing the existence of his father. “And there were six responses in about 10 seconds,” he recalls. Suddenly and wholeheartedly, space was made at the table for the new kid.

There is a parlour game people sometimes play: if you had to choose, would you prefer to remain youthful from the neck up or the neck down? It is Bob Wiener’s great fortune is that he didn’t have to choose. He got both.

On the day we met two years ago, when he invited me for a shrimp salad lunch at the seniors residence that’s now home, it was instantly clear that the athlete he always was—varsity hockey and tennis—is still in him. Having wryly declared himself “the oldest inmate here,” he proceeded, up in his suite, to demonstrate his daily calisthenics: leg raises and dumbbell lifts. He refuses help getting out of his chair. And though he uses a walker now, he still moves fairly briskly down the long corridors of Westmount One.

Just as clearly, the synapses were firing. To hear a supercentenarian with accurate recall of events from their childhood is a surreal experience, like feeling the living breath of history.

In primary school, he remembers, the students made washcloths for the soldiers on the front—of the First World War. As a boy, he watched his beloved Montreal Canadiens play in the old Mount Royal Arena. One of his favourite players was netminder Georges Vézina, who retired in 1925.

On a good day, Wiener can dial up the parade of notable patients who passed through the door of his dental practice, from Charles Bronfman (who left Alouettes tickets as a thank you) to the crime boss Vic Cotroni (who paid cash, had a bodyguard and was the only patient who gave the dental assistant a tip).

In Chicago, where he worked early in his career, Wiener treated a sore molar of the novelist Thomas Mann, who after his last appointment gifted Wiener a signed first-edition copy of The Magic Mountain. A few years later, Wiener visited the Illinois Stateville Penitentiary to attend to Nathan Leopold—half of the notorious murder team of Leopold and Loeb—whose life was famously spared by the skills of superlawyer Clarence Darrow.

A footnote to history: in 1942, Enrico Fermi and his team took over the squash court at the University of Chicago to split the atom and engineered the first controlled, self-sustained chain reaction, paving the way for the A-bomb. Fermi’s eyesight was failing. No one could quite figure out why. As a last resort, the university’s oral surgeon was called in, and he popped out an abscessed tooth that was pressing on the optic nerve, successfully restoring the great physicist’s vision. That surgeon was Robert Wiener.

Wiener’s short-term memory, it must be said, is getting wobbly. But son Neil, who’s Wiener’s main caregiving point man in the family these days, figures his father has earned the right to repeat his best stories.

There is a birth-order effect to longevity: first-born sons, scientists have found, are two or three times as likely to reach 100 as later-born ones. Wiener is the youngest of his seven siblings. But that is the least of this family’s quirks.

A few months ago, on Sept. 16, to be exact, Robert Wiener became the fifth oldest Canadian man ever. No. 6 on the list, the man he put in the rear-view mirror that day, happened to be his brother Dave.

To have two supercentenarian brothers in the same family is vanishingly rare. The odds, Harvard geneticist George Church estimates, are somewhat north of one in a 100 million.

“I am not aware of any other case of two supercentenarians in the same family,” says Stuart Kim, a geneticist at Stanford University and a leading explorer of the genetic basis of extreme longevity. In their own way, the Wiener brothers are as remarkable as the Dionne quintuplets. And in an age when longevity is fetishized, they ought to be every bit as famous. Instead, they are virtually unknown.

Except in the research community.

Eight years ago, when Robert was 102 and Dave was 109, Angela Brooks-Wilson, a geneticist at the B.C. Cancer Agency in Vancouver, worked the brothers in her ongoing “super-seniors” study—a deep dive into the physiology of extraordinarily healthy older people. Getting them both—Dave was the study’s oldest participant—was a coup.

Rather than risking a DNA collection error (usually a DIY affair, the participant spits in a test tube and mails it in), Brooks-Wilson hired a nurse in Montreal to draw blood samples. Then she did a separate study of just the two men, based on their partially sequenced genomes.

Her guess was that they’d have fewer of the alleles—gene variants—known to be linked to the diseases that tend to kill people: cancer, heart disease, respiratory diseases, diabetes and brain diseases. But that’s not what she found. The brothers had just as many of those risk signs as everyone else. So if they had the venom in their genes, as it were, they must also have the antidote. Something was protecting them.

And that, indeed, is the case with the extremely old aged in general. Like giant trees still standing in a forest felled by blight, they seem to have been blessed with a kind of immunity.

Many take health and mobility for granted and live independently deep into their 90s and beyond. Some report having never seen a doctor. Some are almost cartoonishly vigorous—like the 108-year-old Japanese sprinter Hidekichi Miyazaki, who strikes the archer pose of Usain Bolt after crossing the finish line. Or Frenchman Robert Marchant, who retired in January 2018 from competitive cycling at age 106. They have danced between the raindrops of the Big Five Killers and emerged on the other side into a sort of equatorial calm. They have not escaped the inevitable, but they have at least delayed it, by decades.

The question is why. Thus far, fewer than a hundred supercentenarian genomes have been sequenced, and no newsworthy signals have jumped out of the noise. No “strong” gene variant has emerged as their secret tailwind. Nor do the lesser protective alleles we already know of show up in bunches in these genomes. The black box of the supers remains … a black box.

Of course, one really wouldn’t expect otherwise, given that there are so few data points and given a phenomenon as complex as human aging. “You need very large sample sizes to do gene-environment interactions,” says Brooks-Wilson. “The larger the sample, the subtler effect it can find.”

A loose global network of researchers beats the bushes for more of those rare Fabergé eggs — verifiable supercentenarians. Meanwhile, at Harvard, geneticist Church is cutting to the chase. He’s using “gene-therapy” techniques to tweak the expression of key genes involved in cell maintenance with an aim to slowing the aging process and ultimately even reversing it. He has seen promising results with worms.

In inconveniently more complex humans, the keys to the kingdom may be lurking inside the molecular pathways of those slow-aging supercentenarians. Church would love to get a peek at the whole genomes of the Wiener brothers—not just the “hot spots.” He has offered to do the sequencing in his lab for free.

There are no Blue Zones for supercentenarians the way there are for centenarians. There are just too few supers to cluster anywhere. Maybe the closest thing to a Blue Zone for supercentenarians is a particular state of mind.

Robert Wiener is funny, outgoing, quick to laugh and great at loving and being loved. In his job, he called the shots and walked the stairs—an exercise habit that stuck for life. All these things are linked to healthy longevity.

Wiener is ferociously disciplined. His diet follows the recommendations of the Mayo Clinic to the letter (with the very occasional mulligan of a smoked meat sandwich from the Snowdon Deli). He eats modest portions, takes great care of his full set of choppers. If he drops a pencil, he’ll pick it up.

But here is the somewhat ill-spirited question: how much do Wiener’s healthy habits and honourable ways really matter?

Longevity, researchers agree, is around 25 per cent genes and 75 per cent environment, a number established in a famous study of Danish twins. Which means that lifestyle is much more important than genetics for most people. But at around age 75, the balance starts to tip. Genetic luck starts mattering more and what you do matters less. By age 100, genes definitely have the upper hand. And by 110?

“Here is Jean Calment,” the Stanford geneticist Kim says in one of his presentations, showing a slide of the tiny French woman who holds the record for human longevity at 122 years and 164 days. (Calment’s age has been subject to conspiracy theories, all of which have been debunked) “She smoked until age 116. So what that shows is that smoking’s good for you—as long as you do it for a hundred years.” Living well will buy most people an additional seven to 10 years. But if you’re crowding 110, you’re operating out of a different playbook.

And so, at this point, Wiener might be forgiven for wearing sweatpants and eating Cheetos and sleeping in. At his age, wouldn’t you? Especially if you reckoned it didn’t really matter what you did?

Wiener doesn’t think like that. After he reluctantly retired at age 86—most of his patients had died—he did not relax his commitment to his clockwork precision, his fastidious habits. Instead, if anything, he doubled down on them.

Each day, Wiener still goes to his desk with a sense of mission—settling in under a photo of his beloved late wife, Ella. He clips articles from online health newsletters for various family members and manages his charitable contributions. I once asked him if ever sees the movies they show in the cinema downstairs. He shook his head. “Too busy,” he said.

The Japanese have a word ikigai, which means, roughly, “the sense that your life is worth living.” In the earnest application of his impulse to serve, Wiener kindles ikigai every day. And that, too, correlates with longevity, researchers have found. Indeed, the psychologist Howard Friedman, steward of the nine

decade-long Longevity Project, identified a sense of purpose as the psychological factor most central to a long life.

Wiener’s main job right now, you could say, is to be a role model. An inspiration. Not long ago, after retiring from his law practice, Ken Wiener found he suddenly had more time on his hands, and so he signed up for a fancy gym program with a personal trainer. Many athletes use a mantra to help them focus, Ken had learned. So in the gym, he and his wife, Linda, have started applying this mantra when things get tough: if Bob can do it, I can do it.

“Now, sometimes when I’m working out, say on the treadmill, and I’m getting tired, I think, ‘If Bob can do it, I can do it,’” he says. “It helps. It really does.”

Bob Wiener can most definitely do it, still. But in the last year or two some ticks and rattles have crept in. Things happen to the human body as it noses toward its factory warranty, no matter how well the machine is maintained.

Lately, he’s been having trouble keeping weight on. His skin is so rice-paper thin that the slightest bump can produce a cut, sending him to Emerg.

Most frustratingly, his hearing is going—an Achilles heel of the very old, especially men. The left side is almost out, and his right’s not much better.

His eyesight, too, has been failing a bit from macular degeneration. Co-incidentally, the dining room in his residence has gotten awfully dark; they ought to put some decent light bulbs in, he says. “It’s not the lighting. It’s my dad’s eyes,” says his son Neil. “We try to explain this to him gently. But he has a great attitude. He thinks that with a new pair of glasses, everything will be fine.”

Not quite believing you are old is a powerful ace in the hole.

Recently, Wiener hatched a plan to address another issue that’s been puzzling him. He’s been napping more than he used to. He wants to visit the sleep clinic at McGill to see if the doctors there can sleuth it out.

“Um, Dad, do you think it may have anything to do with your being 110?” his son Ken asks.

That hadn’t really occurred to him.