Democracy is not taken for granted in many third-world nations. Here, we look back to when it was a Canadian retiree and election volunteer, Ken Orchard, who played a part in preserving it.

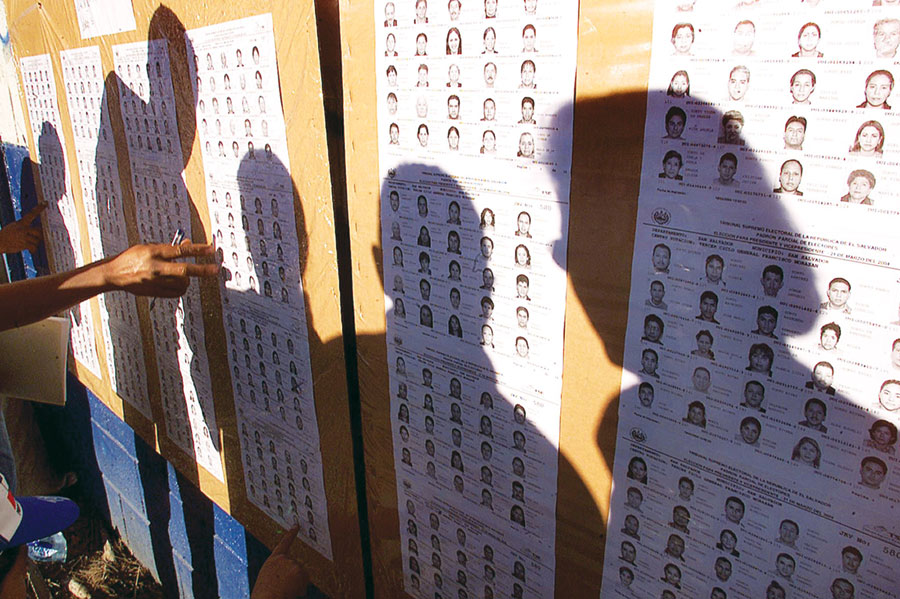

It was election day in El Salvador in 2004, when I and a handful of other Canadians were in a small town about an hour’s drive from the capital of San Salvador. We were up at 5 a.m. to be in the dusty main street of the town to witness the setting up of about 90 voter polling booths. These were generally flimsy card tables with folding legs at which the election officials sat and from where the party-appointed scrutineers, or vigilantes, watched.

Thousands of voters would come from about 30 kilometres around the area in crowded and overloaded old buses with creaking springs and dangerously bald tires, by ox-drawn carts, on horseback, hitching rides on pickup trucks and on foot to join thousands of other voters to choose a new president for El Salvador.

For the voters but also for us Canadian election observers, it was a long, dusty, hot and tiring day. Each observer on my team was responsible for supervising 10 polling tables, and we spent the time, while struggling to stay cool and hydrated, slowly circulating and simply being the eyes of the world that day with our clipboards, observadores T-shirts and cameras highly visible to all. I found that as soon as we began to investigate a situation, it was immediately righted.

At about 10 p.m. that night, when the ballots had been counted by the election officials and watched by the vigilantes representing the four major parties, the ballot boxes were delivered to the local election authorities, and guarded by the police. One of us said to an election official, in halting Spanish, something to the effect of “Well, that was hard work. I hope that it did some good.” The official replied that it did because even though the “good guys” got beat, at least this time they didn’t get beat up.

I was one of a group of nine people from Vancouver Island that had been invited to come and observe the election by the Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad (CIS), an NGO in San Salvador. Before the election, we met with a local community council and discussed the problems posed for them in the election. On the rough stonewall of the council office was a collage of photographs of hundreds of desaparecidos, people that had been taken from their homes in that community, usually in the middle of the night, and never seen alive again. The organizer of these death squads was the same person who had established ARENA (National Republican Alliance), the governing party of El Salvador, and the word being spread was that if the election went against ARENA, the death squads would return. The municipal councillor who told us about this fear element of the campaign had had her two sons “disappeared” during the civil war, which was still a vivid memory to adults in El Salvador.

But the election was also a process of healing. On election day, officials placed the voting tables and poll booths on the side of the street that would get the hot sun in the morning when it was anticipated (accurately) that most voters would show up. At one of the tables near me, there was an intense discussion among the mostly youthful representatives of the four main parties bitterly contesting the election. Eventually but before it was time for the voting to start, each youthful vigilante picked up one corner of the table and together carried the shaky table over to the shady side of the street with election officials in tow with the documents of their work.

Vigilantes from the other 89 voting tables followed suit within a few minutes, and a cooler day was in store for the early voters. Generally, the day was a co-operative effort, rather than the rancorous one that we had feared

Two years later, in 2006, I was asked to participate in the presidential election in Venezuela. The contest was hot and heavy, with the population sharply divided between the incumbent President Hugo Chávez and his opponent, Manuel Rosales.

As in El Salvador, the media strongly backed one candidate. Hugo Chávez won out over his opponent by almost a 2 to 1 margin, with a 70 per cent voter turnout. It was a result that didn’t surprise any of us.

In Venezuela, more than 50 parties exist, and there were 14 presidential candidates. Most got few votes, but they did get their say during the election.

The computer that recorded the votes printed out a ballot, which the voter put into a standard ballot box. At the close of the polls, a random human count was ordered of some ballot boxes to verify the computer results.

So why do I do this? Why not just go on vacation in four-star all-inclusive resorts like other retired persons?

I spent seven years in the ’80s teaching in the electrical engineering departments of technical colleges in Zimbabwe. During that time, I worked through two general elections. In the first in 1985, one of my students came to school very beaten up. His home had been firebombed because it was known in the neighbourhood that he was backing a minority party. But what distressed him mostly were not his bruises but that his books were lost in the fire.

About a dozen people were killed in that town during that election. I was able to replace the burned books and help the student get back on track with his education but, in my contract, I was forbidden from involving myself in any way in the political processes of Zimbabwe.

Given the colonial past of Zimbabwe, the requirement for non-involvement by foreigners is totally understandable. But still, I resented having to choose one type of contribution over another. My technical knowledge was sought after, but my social conscience had to stay on the shelf.

Now that I’m retired, I get to have it both ways. I can apply my knowledge of social and political processes and exercise my long-standing commitment to free and fair elections while enjoying the stimulation of a foreign culture. And I can be connected to local community while out of Canada.

Seldom is there any real danger for observers if one is culturally sensitive and uses one’s head. Those principles weren’t in play in San Salvador before the election when two election observers from the U.S. were in an Internet café in San Salvador, sitting back to back at their terminals and conversing very loudly in English. I don’t know firsthand what they were saying but, suddenly, both had pistols against their temples. They were told to hand over their observer credentials or die. Fortunately, they decided not to invoke the U.S. constitution on that occasion, and both lived to go home before the election.

We had been cautioned about that by CIS during our orientation sessions and about other safety hazards, such as the many security guards on the streets of San Salvador packing shotguns. A conflict with one of these private security guards in San Salvador left a Salvadorian dead across the street from our hostel.

But I’ve been fortunate and have avoided any such incidents on my watch.

Next up for me is the presidential election, once again in El Salvador this March. It will be intensely contested because of the crisis in the American economy and El Salvador’s dependence on remittances from family members working in the U.S. Should El Salvador remain integrated with the U.S. (it has even adopted the U.S. dollar as its official currency in 2001)? Or is Venezuela perhaps a more stable model for development?

Whatever the decision, in that election, I’ll be happy to be part of a team assisting in the decision-making process. In return, I’ll continue to experience the stimulation that results from getting out of my comfort zone from time to time. Especially when I feel the wet and dark Victorian winter months coming on.

A version of this article appeared in the March 2009 issue with the headline, “Guarding The Ballot,” p. 24.