Talkback: An Interview with Playwright Judith Thompson

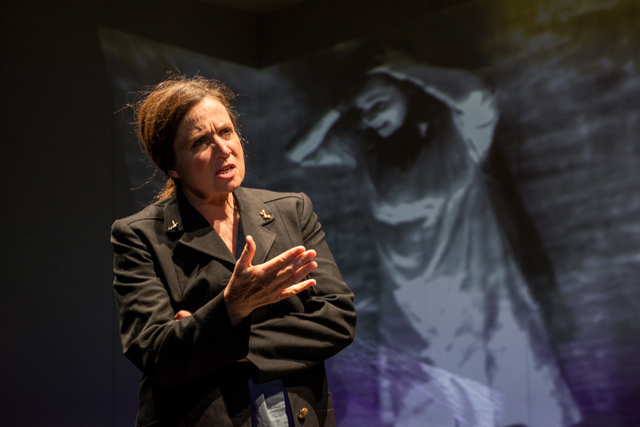

Photo by Wendy D

If playwright Judith Thompson were one to rest on her laurels, she’d have no shortage of theatre awards, accolades, hit shows, and even an Order of Canada, on which to prop up her feet.

Luckily for theatre goers, Thompson, 59, isn’t ready to kick her feet up just yet. Take her latest production – Watching Glory Die – based on the tragic story of Ashley Smith, a Canadian teen who hung herself in her cell in a Kitchener women’s institution while the guards obeyed strict orders not to intervene.

The play has three characters – teenage inmate Glory, her mother, and the prison guard – and Thompson plays them all. It’s a daunting task for any performer, let alone someone who hasn’t acted on stage in 35 years.

Zoomer’s Mike Crisolago spoke with Thompson to discuss her decision to take on such a challenging performance, how the Ashley Smith tragedy inspired her to write this show and her trick for memorizing all of her lines.

MIKE CRISOLAGO: You haven’t performed on stage in 35 years. Why make your comeback in a production in which you play all three characters?

JUDITH THOMPSON: I know, isn’t that insane? [Factory Theatre dramaturge] Iris Turcott, said, “I’m doing a festival and writers are performing and working…” And I said okay, because I thought it’s time – I was 57 at the time – to take up challenges. Do what scares you. We all have friends who are dropping with terrible illnesses and I just thought there’s no time like the present. And do something that’s really, really kind of frightening.

And what was frightening in the end … really was just the memory work. When I was a young actress, in Q&A’s when people would ask how you memorize all those lines we’d just kind of snicker to ourselves because it’s just not even an issue when you’re young. But in this one – partly because it’s mine and we did so much dramaturgy in the first couple of weeks of rehearsal – everything changed so it was really hard for me to learn it. And I could only learn it with mnemonic devices, like if the word “red” is in one paragraph and the word “barn” is in the other, just remember “red barn.”

MC: So once you actually started performances in Vancouver did your memorization hold up?

JT: Completely. And I got into a wonderful routine where I had bought a second-hand bike, I biked the seawall in Vancouver, which was just sheer heaven because it was beautiful weather, and I’d sit at one of the beaches and I’d do the whole play to myself. I’d skip a line here and there (on stage), and that was my big secret I learned as a playwright – that nobody ever gets your play perfect. I sort of was under the illusion they were.

MC: When it comes to Watching Glory Die, was there a particular moment during the Ashley Smith inquest that compelled you to write this show?

JT: It was a moment that was difficult for me because my daughter was in the hospital with a hip replacement – she has an early juvenile arthritis. That was also the time of [Iris Turcott’s] festival. So Ashley and the horrible tragedy of her death – I think that what connected it for me was my daughter, in a sense, incarcerated by this illness and having to be in the medical system. So this is my artistic response to something that affects all of us and something, as taxpayers, we don’t know what’s going on everyday. I’m lucky enough … that many of my plays are still playing 30 years later somewhere, that it (could) go on in different languages (and) address this tragic lack of response and how the government can get out of our control even in democracies.

MC: So many of your shows are influenced by current events. What perspective do you believe we as viewers gain when an artist takes an event that touches so many people and distills it through their work?

JT: I think probably what it is, in this case, it’s the guard. Because we all think, how could anybody just stand there and watch someone turn blue and not go in? But that’s us. That’s what speaks to us because here in Toronto, we all pretty much step over homeless people in the winter knowing there’s a good chance they might not survive the winter, or the night. Why aren’t we out lobbying the next day? We do what we can, we give a bit of money, but in a much broader sense we’re in the same position as the guards where they got used to [Ashley’s] tying of the ligatures. To us it seems unimaginable you’d be accustomed to people hanging themselves, but it was five or six times a day, everyday. So I’m trying to say we are those guards, and who amongst us has the strength of character, or the private income, to stand up against rules and orders we don’t like and say, “That’s it. I’m giving up my salary, my pension”? We all should be trained to be so strong in character that we will defy unreasonable or unethical orders but right now we are not.

MC: If you were writing a sequel to this show 10 years from now, what do you hope we as a society will have learned/improved in the wake of this tragedy?

JT: Some people are saying, even in the press for this, that it’s about how the correctional system treats people with psychiatric illnesses. Well, she didn’t have a psychiatric illness. The system really did, in a Kafka-esque way, shove her into a corner. And her mother doesn’t think she wanted to die at all – that it was just another tying a ligature. Trying to get attention, trying to get the guards in there so she’d have some interaction. But I don’t know, as a performer and a writer I think there’s definitely despair in the mix because she was supposed to get out and then they rescinded that because she, I don’t know, said a swear word or something.

So once I sort of dived down this rabbit hole of this insanity that is our correctional system and brutality – and yes, some people do need to be in there – but there are so many that shouldn’t.

MC: You got to know Ashley’s mother personally. Did she offer you any glimpses into Ashley’s struggle that you could incorporate into this play?

JT: Yeah. I incorporated all of it right away. She said…(Ashley) did not want to die, she wasn’t difficult, she was treated so abominably – this reputation is what the guards were responding to, not her. So I put both points of view in. I’m sure the truth is somewhere in between…And some of (the guards) are lovely. I read the testimony at the inquest and they didn’t like these orders [to not intervene] either.

MC: Going forward, if you continue to perform do you envision yourself taking on a show such as this, playing all three parts?

JT: No, it’s so exhausting. [Laughs] It’s elating in a way … but I like to be in my shows as a small part because I hate abandoning them. I hate leaving them and then our lives are so busy I’ll see them maybe twice, or three times. Although it’d probably be annoying to the actors to have me there. [Laughs] But I like seeing others do it.

Watching Glory Die runs until June 1 at Toronto’s Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs. Click here for performance and ticket information.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.