To Infinity & Beyond: Defying Gravity In Alabama

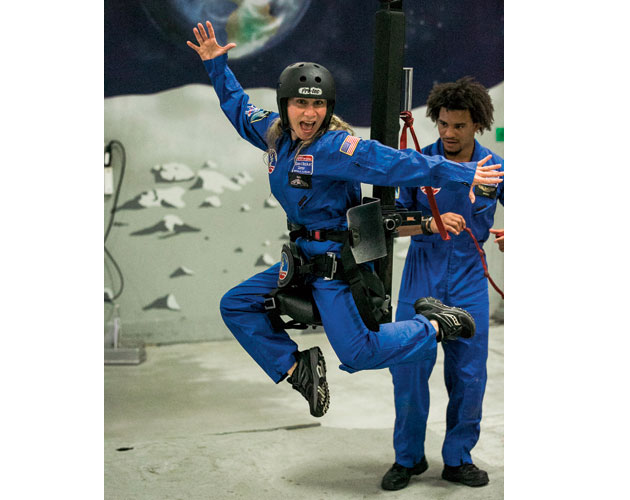

Photo: Vivian Vassos, moonwalking

It was 59 years ago (July 29, 1958), the U.S. Congress established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a civilian agency responsible for America’s activities in space. So how’s this for a timely travel idea? Go for a walk on the moon — in Alabama.

Could we walk on the moon? Dreamers, some said. Dreamers, like Gene Rodenberry, who created Star Trek; and U.S. President John F. Kennedy, whose drive to beat Russia in the Cold War-driven space race, launched NASA into our psyches. I find one such dreamer, Charlie Johnson, at the Marshall Space Flight Center near Huntsville, Ala. Johnson used Roosevelt’s GI Bill to help make that dream come true. The Korean War vet was an original member of the team that built the Saturn V rocket, capable of carrying a human to the moon, in the early ’60s. Johnson, now in his 80s, works as a volunteer docent at the facility. He’s still spry and cheeky, winking at the gals while telling his back-in-the-day stories. But before Johnson and his engineering skills helped build the propulsion rockets that pushed seven million tons into the sky, there was another calculating Johnson, but she was hundreds of miles away, in Langley, Va.

For those who still haven’t seen it, the Oscar-nominated box-office juggernaut Hidden Figures is the true story of the math genius Katherine G. Johnson who, despite gender (female) and race (African-American), “conditions” that, in the early 1960s could practically be insurmountable obstacles to success (hmm, plus ça change …), calculates impeccably, how Mr. Kennedy is going to get his boys to the moon. But that was then.

But why space now? The Russia equation is back, with Cold War-ish daily headlines, just as the NASA telescopes have discovered a group of exoplanets—planets that are very much like the Earth. In February, Tesla’s Elon Musk announced his Space X program would be able to slingshot two tourists around the moon and back by next year and, in March, Karl Lagerfeld launched a massive “rocket” at his show for Chanel in Paris.

But the fascination for space regained a momentum a few years back, when, like a shot in the arm, a mustachioed guitar-toting engineer and pilot, Chris Hadfield, from Sarnia, Ont., commanded the International Space Station and reignited our stargazing imaginations. Could it be because we feel a sudden need to escape? To reach for the stars once more?

It’s at Charlie’s NASA outpost that I find myself, clad in a blue pilot’s jumpsuit, strapped into a seat that’s anchored to an orb-shaped contraption, like a circular cage. It’s part of Space Camp, a program that any dreamer can sign up for, not just kids. The machine, the Multi-Axis Trainer (MAT), starts to spin, at first like a swing, but then you’re somersaulting, forward, backward, sideways, never the same direction twice. It was used extensively to condition space cowboys against disorientation during the Mercury program, the first manned space flight program at NASA and the very same project that Katherine G. Johnson helped make possible. John Glenn, the first American to orbit the earth and “touch” the stars, trained in this contraption. And, now, so have I.

Next up, we’re going to the moon. What’s it like to feel almost lighter than air? The one-sixth gravity chair gives us a hint. Because the moon has one-sixth the gravity of earth, astronauts’ suits had to have an element of weight in them to hold them down. But when given the chance, they could also jump and skip like feathers in the breeze and come down just as softly as they traversed the moon’s surface. Pilots training during the Apollo program would use these types of chairs to learn how to moonwalk. It’s not as easy as it looks: balance and focus are important; an almost ballerina-like posture helps keep you from falling forward or veering off course. Neil Armstrong trained in this contraption before he took that giant leap for mankind. And, now, so have I.

As a final team-building exercise, we launch a simulated space mission to Mars. Some of us will man mission control, some of us will work the command module and some of us will be sent out in spacesuits to make repairs and even tend the garden greenhouse. We watch the weather, drive space rovers on Mars and direct our fellow astronauts as they climb into “space” and repair malfunctioning parts on the outside of the module. Our mission was a success, of course. All the repairs were made, and our little garden would keep us fed for another day. As The Martian, Matt Damon’s botanist character created his own little garden on Mars. And, now, so have I.

If you go There are three- and four-day programs. www.rocketcenter.com; www.spacecamp.com/adult

A version of this article appeared in the May 2017 with the headline, “‘Scuse Me, While I Kiss the Sky,” p. 78.