Standing Ovation

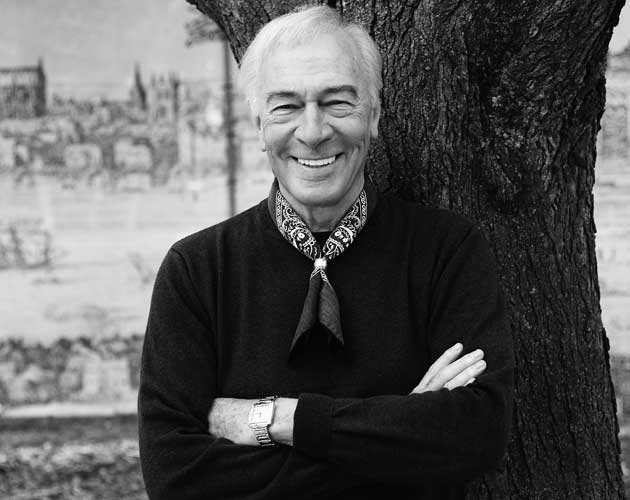

The always dashing and gentlemanly Christopher Plummer, 78, speaks to Kim Izzo about his memoir In Spite of Myself as well as keeping young, his next great film role and a little movie he made in the 1960s set in Austria.

KI: What prompted you to write the book at this point in your life?

CP: Many years ago, maybe 10 to 15 years ago, [legendary publisher] Jack McClelland suggested it one night when we were at a party. “Chris, why don’t you write a book? You have an interesting background here in Canada, you’re a loyal Canadian and you probably have lots of stories to tell.” So I decided, why the hell not? I do have stories to tell. And so I started. And I began to write and began to like writing.

KI: I was surprised to find you never kept a diary all those years. How did you recall everything? There’s so much detail in the book.

CP: I go by what I was in that year — what film I was in or what play I was in and where it was. And that brings it all back, and all the other stories fit in. I have a good memory.

KI: You say more than once in the book that your behaviour at a given time was “unconscionable.” At what point in your life did you rethink your earlier behaviour?

CP: I think that’s a common problem, not just mine. When you’re young, you’re either naughty, rebellious, you drink too much, you play too hard. And you sort of take a look at yourself a little later and say to yourself, “Wait a minute. I can’t keep doing this. I’ve got to get some discipline going.” And I worked awfully hard in the theatre all through my earlier days, so I felt I deserved to go crazy when I was off the stage or off the camera. And one liked to be wild. But we were all like that. I have so many friends in the business, both in England and New York, who were wonderful two-fisted drinkers and rebellious, naughty fellows. So it was fun to be in that club.

KI: Was it difficult to be so revealing when it came to your way about the ladies?

CP: Not at all. None of it is gossipy. I don’t really name them. Only once or twice do I admit that I had an affair with somebody — for good reason, because I was very impressed by them or they guided me from an early age; the older women did. That was part of one’s life growing up, experience. None of it is salacious and none of it is sensational. I wouldn’t have written it if it was. I’ve always loved women. Is there something wrong with that? I adore women.

KI: You refer to The Sound of Music rather naughtily as S&M and you weren’t so fond of it at the time. But at this point in your life, can you see the magic of the film?

CP: Indeed, it’s a very good film of its genre. It’s a wonderful musical movie — it’s fabulous. But it’s just not my cup of tea.

KI: Did you feel stereotyped after it?

CP: For a while. But the minute I hit a certain age, I was a character actor and the roles were much more interesting. I go back and forth all the time [between film and theatre]; I make that a sort of rule with my life so that it’s not monotonous. Variety is the spice of life.

KI: You also were a sort of snob when it came to the cinema and preferred the legitimate theatre. Did the success of The Sound of Music change your opinion?

CP: I think money changed my opinion — and also it’s a fabulous medium and I’m a huge fan of the cinema anyway. I always have been.

KI: Next year you have the lead role as Leo Tolstoy in The Last Station opposite Helen Mirren and James McAvoy. Making that film must have been a great experience.

CP: It was just wonderful working with Helen. I love Helen Mirren. I’ve known her for years, but I never worked with her. So I was thrilled she was there and also when [director] Michael Hoffman asked me to play Tolstoy. Because it’s all about their late relationship as husband and wife. And they fought so terribly and they dealt with each other in such passionate ways. So I think it will be a terrific little film. There’s a lot of comedy in it, as well as a sort of deep feeling for each other. I think it ought to be very good. I felt very good about it. Helen is wonderful in it and so is James McAvoy; he’s just terrific.

KI: You said that once you hit a certain age, you became a character actor, but Tolstoy is a leading role.

CP: What I mean is that they were characters, well-written, over 40, let’s say, and not romantic leading men, which can be an awful bore to play. But the more mature characters are fascinating to play because there’s some depth and maturity about them. Certainly I’ve done a lot of biographical figures; I’ve played so much. I don’t think anyone has ever done anything about the Tolstoys as a film. I think it was too vast a subject.

KI: Did you think you’d be this busy at this stage in your life?

CP: No, I’m thrilled, I’m absolutely knocked out by it. It just keeps you young working like this. I don’t feel old at all. I mean, I feel pretty much as I did in my 50s. I still have the same amount of energy.

KI: How do you keep young and fit?

CP: Well, I have a marvellous wife who cooks absolutely beautifully. And she cooks unbelievably well-balanced meals without all the heavy sauces and starches. She knows exactly what to replace certain ingredients with. I’ve played tennis all my life and still work out. I walk every day. It’s a profession where you’re always on your feet; it requires movement all the time, so you’re not sedentary. That, plus the good diet, I suppose, keeps one in good shape.

KI: Do you have any plans for retirement?

CP: No, I have lots of engagements coming up. I’ve got films and theatre well into my 80s so far. If I don’t make it, then I’m sorry. But I’m determined to try. There’s no such thing as retirement. I think it’s death. Retirement and death are synonymous.

In this exclusive excerpt from his newly published memoir, In Spite of Myself, Plummer writes about his early days at Stratford and reveals a side of himself – Raucous, silly and, yes, inebriated – that few have seen:

Stratford’s tent had been struck forever and with it a wonderful sense of living dangerously. Now, everything would be “safe”— perhaps too safe. At last we could boast a roof over our heads; in fact, we were permanent; the only “established, permanent crap game” of its kind on the continent. Our cocoon was sealed. Except for the few free spirits who knew they must one day cut the old umbilical — the future seemed assured.

To celebrate the new structure there was a series of gala functions and two strenuous opening performances of Hamlet and Twelfth Night. The affirmation of several seasons of glorious work came on the second night with Tyrone Guthrie’s magical production of the latter when an international audience, as one body, gave the new enterprise a jubilant welcome. Our revels had by no means ended. Most of the company went way over the top — the festivities continuing far into the next morning — not just on the banks of, but deep in, the Avon River itself; drunken heads bobbing up every so often to shout triumphant obscenities at the indifferent sky.

It had completely slipped our minds of course that the dear, inconsiderate management had scheduled a matinée of Hamlet that same day at 2:00 p.m.! Puce with rage, we dragged ourselves from the murky shallows, bedraggled swamp creatures, sodden with lake water and booze, and dutifully reported to the theatre, where we began pouring ourselves into our gear. My old friend, that bruiser of an Aussie Max Helpmann (who played the Ghost), had actually never left his spanking new dressing room — in fact he’d been quietly celebrating there for days. Max was the swarthy brother of the famous ballet star Robert Helpmann. While Robert spent the war years grand jeté–ing his way to fame on at least four continents clad in a variety of toe shoes, Captain Max amused himself during battle breaks in the Pacific campaign by driving motorcycles off the decks of aircraft carriers into the sea far below. A daredevil, cursed with shyness, you couldn’t find more of a man’s man if you tried. A veteran in the theatre of war and a warring veteran in the theatre, he was a seasoned expert at burning candles at both ends. At this moment, true to form, having downed his last drink, he was just packing up to go home and pass out when we arrived to break the sad news. “Turn around, Max, you’re going the wrong way.” Poor Max, in this rigid state, struggled manfully into his heavy fiberglass armour and ghastly green makeup and glided rather unsteadily onto the stage — “my father’s spirit doomed for a certain term to walk the earth.” “Hearsed in death,” he looked like we all felt. I could have sworn I heard Hamlet, perhaps it was me, shriek, “Go on, I’ll follow thee” as I crawled after him up the steep staircase. We were on our precipitous way to the little balcony on high where we were to play the famous scene between Hamlet père et fils. The balcony had no railings, and there was barely enough space for two — certainly no room for a waiter with a tray of much-needed Fernet-Brancas. A tiny spot lit both of us — the only light source, everything else in stygian gloom, including the audience. Below us, nothing but a gaping hole — not even a trace of the stairs we had just mounted. From the way Max was swaying up there, the lines he was spouting — “List, list, o list” — took on a fresh and special significance.

“Brief let me be —” insists the shade and proceeds to unfold one of the longest and most tortured tales in theatrical literature. I know one is not supposed to touch a ghost onstage or off, but as “Dad” rambled on I had no choice but to grab hold of his legs to keep us both from hurtling to certain death. Rivulets of escaping booze poured down his face melting his deathly green makeup until he resembled the decomposing Mister Valdamar, but he managed to get to the end of his lengthy message quite superbly and without a hitch! “The glowworm shows the matin to be near” was his cue to take leave of the platform and glide gracefully and soundlessly down into the enveloping darkness. Max gingerly began his backward descent into the black. Oy! Could he have used a glowworm!

With his first “Adieu” he made the top landing but there was a tremendous thud as he collided headlong into a pillar — the balcony shook. I was certain I would never set eyes on my friend again. I could hear him swearing all too audibly as he feverishly groped his way about. My poor old specter was irretrievably lost. I prayed his undercarriage would lower and he could land safely. Finally he decided to give up being a silent ghost altogether and began to stomp angrily down the rest of the staircase in his clanking boots of mail. This phantom was taking forever to disappear and advertising every step of the way. To cover its uncertain journey it kept repeating “Adieu” and “Remember me” many more times than the Bard had intended. At long last I heard him reach the apron of the stage. All he had to do now was to tiptoe unseen down the ramp and be done. I steeled myself for my soliloquy, which would follow (“O, all you Host of Heaven …”). The earth gaped, the Hosts of Heaven were poised, all Hell was standing by waiting to be coupled. I was just opening my mouth to let fly Hamlet’s exclamation of release when with a prolonged clatter much like the sound of garbage cans colliding in a tin laundry chute, my father’s spirit catapulted and ricocheted down the ramp and disappeared far below into the cellarage. There was a long, deathly silence. Then a pitiful little voice from somewhere in the subterranean bowels called out one last “Remember me!” Remember thee? How could I fucking forget?!!! Ah, mes amis, ’twas by no means the finale of that wacky afternoon! For a while at least, things began to resume their normal expectancy and settle down. Hangovers were being sweated out one by one and, for a spell, most of the large ensemble managed to get back on track. Then a sudden sea change occurred, for the general pace now took on a most alarming speed. Clearly there was but one thought on everyone’s mind: to get shot of the damn thing as quickly as possible. It was a race to the finish. To a man, each actor seemed determined to get the hell off before the next guy. This new, unexpected attack gave the performance a certain urgency and passion not experienced before. It is now the graveyard scene. Hamlet leaps into the grave gathering the dead Ophelia in his arms:

Forty thousand brothers

Could not, with all their quantity of love,

Make up my sum.

Our grave was an open trapdoor in the center of the stage. At the scene’s conclusion, I would climb out of the trap and slam it shut, on the lines:

Let Hercules himself do what he may,

The cat will mew, and dog will have his day.

It was necessary to close the trap in order that the remainder of the play could be performed on the full stage. That day I was not the only one to leap into the grave. A young and overzealous French Canadian lad (un véritable étudiant du drame) who played one of the monks, had, in his religious fervor, leaned too far forward, lost his balance and dove in with me. This would have been perfectly okay had he climbed out when I did. But, not wishing to distract, humiliated beyond repair and out of a certain deference to the leading player, me, the damn fool remained down there out of sight. No urgent eye signals from me could persuade him otherwise. I had no choice but to slam the trap on them both! There was a low rumble of stifled amusement from the audience and for the rest of the afternoon the only thing they could think of was “What the hell was a young monk going to do for the rest of his days shut up in a grave with the dead daughter of Polonius?” The answer was all too obvious — necrophilia!

The afternoon limped on, teetering as always on the edge of disaster. Was this the Hamlet I had grown to imagine would perhaps, in the annals of theatre, be a tiny milestone? Was not New York opening its widespread arms? After all, there had been rumors on the street that I might be the awaited Prince — the Dane of the moment. Managers, producers, promoters were on red alert for the signal that would be their assurance of a Broadway production. One of them, Roger L. Stevens, had arrived the night before for the opening of Twelfth Night and would stay over to view Hamlet this very matinée. Roger had always shown great kindness to me over the years since he co-produced Miss Cornell’s Dark Is Light Enough and the Paris Medea of Judith Anderson. We had been drawn closer together because of my longstanding friendship with his partner and pal Robert “Ratty” Whitehead. Yes, if anyone was to produce my Hamlet, he would be the one! Roger was a laid-back, speechlessly shy American businessman who became very rapidly one of the most significant theatrical patrons in the United States, and principal advisor on the arts to several presidents (Democrat and Republican), starting with his old friend John F. Kennedy. He also founded the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and was a prime mover in real estate both in Washington and New York City. In his long and distinguished career, it could be said of Roger that he never rose — he was always up there! He was on so many boards it was sometimes difficult for him to remember of which ones he was chairman! In fact, he had already earned the somewhat endearing reputation for being irritatingly vague and absentminded. Once, so the story goes, he was forced to entertain some highpowered, out-of-town executives who insisted they be taken to El Morocco, the then-exclusive New York nitery. Now, conservative Roger, who had at one time owned the Empire State Building and several other such landmarks, never went to nightclubs — indeed he hardly ever went out at all. He certainly had never been inside El Morocco. When supper was over, he called for the bill so he could sign it. The management was sorry, but they didn’t know him and would he please pay cash or cheque. Too shy to tell them who he was and make a scene, he admitted he had no cash or cheques with him. The out-of-towners he had entertained so lavishly had had such a great time ogling all the glamorous ladies they fought like terriers over the bill, insisting they take him. Roger was mortified. The next day when arranging with his secretary to reimburse them by mail, he told her of his predicament with El Morocco’s manager. The secretary, dumbfounded, could only say, “But why didn’t you tell him, Mr. Stevens?”

“Tell him what?” “That you own that building.” That was Roger. So it didn’t come as too much of a surprise when I learned what had happened. Fighting as hard as I could through last night’s vapors to give him the best Hamlet I knew how, I might as well have been baying at the moon. Our man wasn’t there! He’d forgotten to come. In fact he hadn’t even been to bed! The previous night’s celebrations had got to him as well and he was still partying away over at Siobhan McKenna’s house. The captivating Irish actress and nighthawk who played a wonderfully lyrical Viola in Twelfth Night had the day off and was taking full advantage of it! And Roger was smitten! Here was his new star! Good-bye Hamlet! So long, Broadway! While I was vainly acting my heart out, the absentee entrepreneur and his newly discovered Colleen at midafternoon were shouting Irish ditties at each other in raucous disharmony, which the loudest cannon in the Elsinore artillery could not have silenced!

Excerpted from In Spite of Myself: A Memoir. Copyright © 2008 by Christopher Plummer. Published by Alfred A. Knopf Canada. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.