Author M.G. Vassanji Goes Home to Many Places

Toronto writer M.G. Vassanji eloquently sums up his new non-fiction book about his homeland of East Africa — and the motive for writing it — in just four words: “Human beings live there.”

He explains, “For someone who knows the place, it’s a place of life. Others see it as a place where everyone is dying and hungry.”

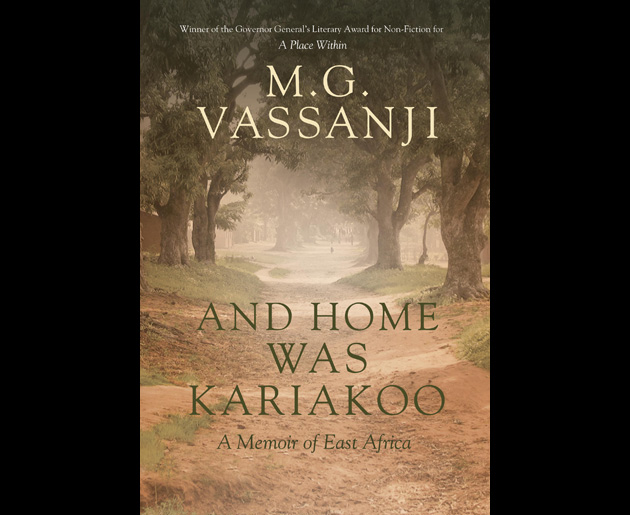

Part memoir, part road trip, part pilgrimage, And Home Was Kariakoo takes the reader on a compelling journey of discovery.

Moyez Vassanji is a guide whose sense of belonging animates every paragraph. He’s the ideal companion on interminable bus trips, evoking the tedium and the humour. He shares with us delectable kebabs and chapatis in tiny, hidden shops and revealing conversations over fragrant cups of tea.

For most Canadians, “Kariakoo” will be an adventure in a distant, exotic area of the world: Zanzibar, Timbuktu, Serengeti, Kilimanjaro.

For the author, a two-time winner of the Giller Prize, it is also a journey of discovery involving distance — “re-examining my own life from a distance and a distance in time.”

Vassanji was provoked into writing about his homeland in part by authors who view East Africa as an alien place, including Paul Theroux.

“He paints it as a dark continent,” says Vassanji, as genial and generous in person as he is on the page but no fan of Theroux. “Being an American, he worried all the time about how he smelled, about deodorants.”

Instead of grumbling about how “foreigners” wrote about his homeland, instead of “throwing books at the TV,” he decided to write about it himself.

Vassanji’s previous book, The Magic of Saida, was a fictionalized tale of a man much like the author: Canadian, of Asian heritage, who returns to East Africa which was home.

As with so many aging boomers — Vassanji is 64 — he was drawn back to the places and experiences of his childhood.

“I thought I would like to travel there,” he explains, “all those names, little villages spread out all over the place.

“It’s nice to go to a small place and hear the local noise. That’s what life is.”

He discovered again the vastness of his homeland and the diversity.

“The country changes from coastal to semidesert, from lake region to forest. People’s features change and the shape of their huts change. Language changes.”

But, he says, “Wherever you are, acceptance depends on you.”

Vassanji left Tanzania to study physics at M.I.T. in Cambridge, Mass. in the 1970s.

“I recreated myself, now to the point where I feel at home in many places.

“Toronto is home. My kids were born here and went to school here, I vote here, I mow my lawn.

“When I go to Tanzania, I feel at home also. India feels like a certain kind of home. A certain part of me feels comfortable there.

“What I find frustrating,” he says, “is that it took me decades to realize you don’t have to be just one thing.”