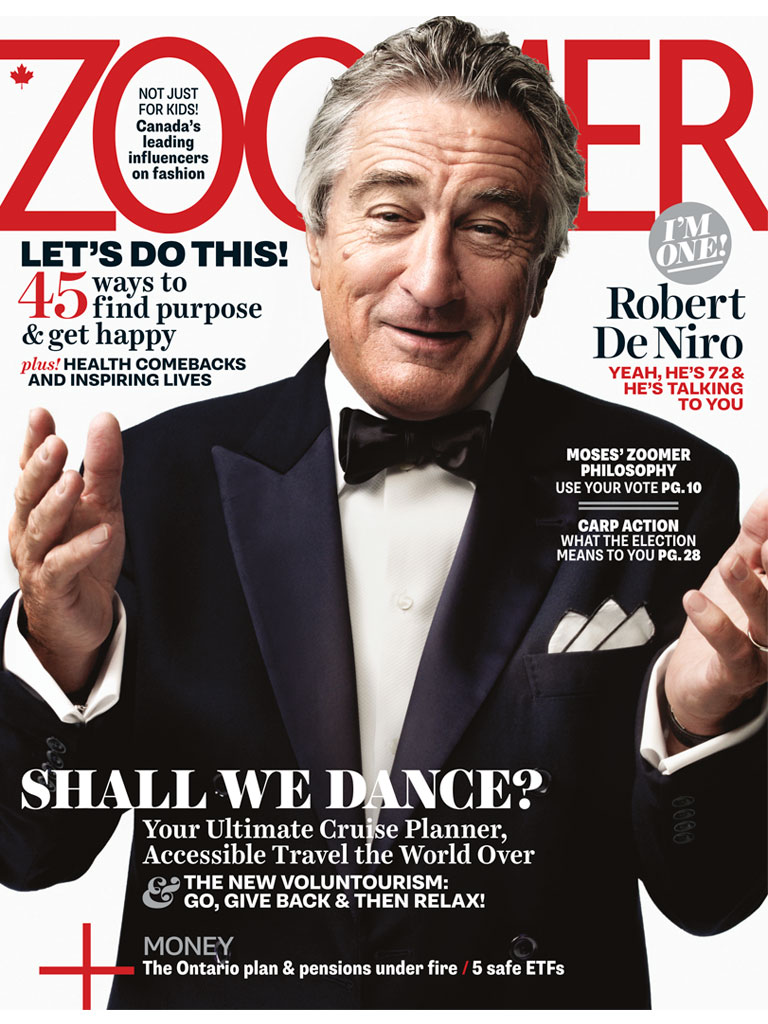

Robert De Niro at 80: Revisiting the Time He (Sort of) Opened Up About Family and Film

When Robert De Niro sat down with Zoomer contributor Johanna Schneller for a 2015 cover story, the screen legend — who turned 80 this week — let his career speak for itself. Photo: Art Streiber/August

Robert De Niro turns 80 today (Aug. 17), mere months after announcing the birth of his seventh child back in May. But that’s not the only exciting news that the screen legend has going for him as he enters his octogenarian years.

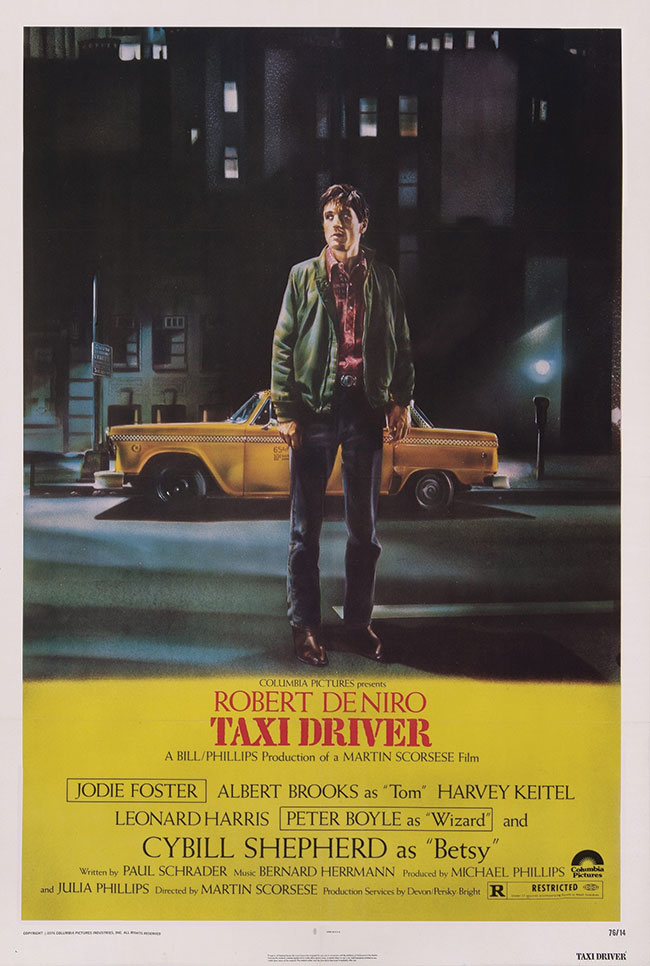

De Niro’s next film, Killers of the Flower Moon, directed by longtime collaborator Martin Scorsese, garnered rave reviews at the Cannes Film Festival this past spring, ahead of its theatrical opening in October. And with Oscar buzz already growing for the two-time Academy Award winner, Gold Derby pointed out that, should De Niro win a statuette for his role in the film, he’d set a new record for longest time between Oscar wins. De Niro won his last Oscar, for Best Supporting Actor, in 1981 for Taxi Driver. A win at the next Academy Awards would make it 42 years between statuettes, breaking the current record of 39 years between wins held by Helen Hayes.

Until then, we’re marking Robert De Niro’s 80th with a look back on our 2015 cover story with the legendary actor — which turned out to be one of the most unique interviews in Zoomer‘s history.

A perk of being one of the greatest actors of all time: you have your own trailer. Robert De Niro has had his for about 15 years. It shows up on all his film sets. It’s not tricked out, except for dozens of framed photos of friends and family. But it immediately becomes the centre around which every shoot revolves.

“It’s like you’re in his living room,” says the writer-director David O. Russell, who has made three films with De Niro (Joy, American Hustle, and Silver Linings Playbook, which earned De Niro an Oscar nomination). “Part of that is the people who are there. Part is the food—he serves the best Italian food wherever he is. And a certain kind of music is playing, the best music, or a certain kind of news or movie is on the television.” It’s not pretentious, Russell insists; De Niro favours simplicity and humility. It’s simply a physical manifestation of who he is and what he’s about.

“Picasso once said, ‘I like to live like a poor man who has a lot of money,'” Russell continues. “I think that’s how Robert lives.”

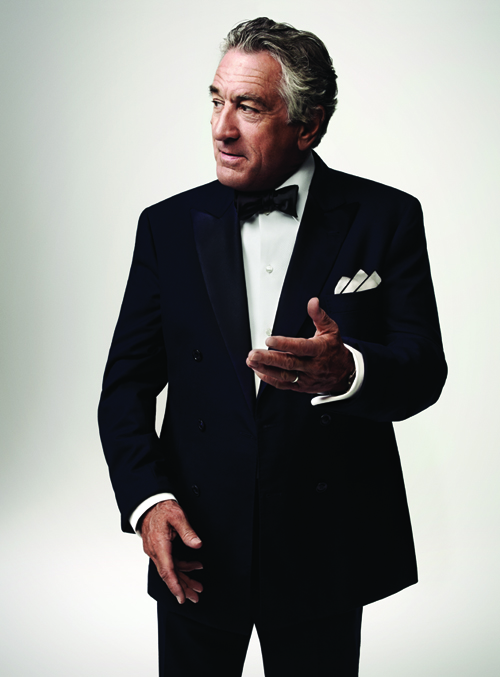

Certainly, when De Niro arrives for a 25-minute interview in a posh New York hotel suite, he doesn’t look pretentious. He’s wearing shorts. Olive khaki cargo shorts, an olive polo shirt, and snappy black slip-on sneakers. Everything is expensive-looking but deliberately casual. He’s tanned and thin, with toned arms and legs. His salt-and-pepper hair is longish, with a slight curl; his skin clear and barely lined. He looks younger than his 72 years, sexy. He sits on the sofa, crosses his legs and orders tea with lemon.

De Niro is a notoriously tight-lipped interviewee. I saw him on stage a few years ago at the Tribeca Film Festival, which he founded in 2002 to help reinvigorate downtown Manhattan in the wake of 9/11, in front of 3,000 people, and he said so little that his interlocutor was openly mopping sweat off his face. With me, he’s the same. He speaks softly. He deflects. Ask him, for example, what he likes about this phase of life, and he responds, “Certain things.” Ask him if violent scenes are taxing to play, and he says, “They’re hard in some ways, not in others.” Ask him what kind of a kid he was, growing up in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, and he says, “In some ways, I was a little wild. In other ways, I had common sense.” Press him: Wild how? “It’s too difficult to explain.” Did you ever get in trouble? “Here and there a little bit.” Can you tell me about one time? “Nah.”

Somehow, his terseness isn’t rude. His non-answers are affable. He makes eye contact. He maintains a pleasant expression. Occasionally, a sly smile sneaks across his face (more on that later). He doesn’t seem to mind the questions. He simply doesn’t care to elaborate. He does have one verbal tic, though: a two-word defence system. When he finishes an answer, he gives a slight and slightly impatient shrug (familiar to anyone who’s ever seen him play a gangster) and says, “That’s it.” So: How do you relax? “Reading a book, going someplace quiet with the family or even by myself sometimes. That’s it.” Why do he and director Martin Scorsese, with whom he’s made eight films, work together so well? “Marty gives you a lot of leeway. At the same time, he directs. That’s it.” Believe me, when Robert De Niro tells you, “That’s it,” that is indeed it.

Initially, it’s hard to square this taciturn fellow with the artist whose trailer is always hopping. At one point, I ask De Niro if he gets through interviews by playing the role of reluctant subject. (His Everyman shorts are clearly a wardrobe choice.) “Oh, I’m way past that,” he answers. But he is playing a role: that of a respected actor determined to protect his privacy. One who’s figured out how to float above the fray, how to be just bad enough in interviews so no one asks him too often. How to do his duty and slip back unscathed to what he really cares about: his family, his businesses, his art. Like all his roles, he plays it well.

We live in a golden age of acting, in film, television and theatre. Every generation has a dozen greats. Yet after six decades in the business, De Niro still hovers above them all.

“He has so much artfulness in commanding a character inside the narrative,” says Michael Mann, who directed De Niro in the heist movie Heat (1995). “He has a sense of scale that’s extraordinarily calibrated and precise. He knows how much to feel, how much to allow himself to react. It’s artistic wisdom. You don’t realize how perfect his perception is until you have the whole movie together. Film editors and directors wonder at it.”

During the Heat shoot, actors like Val Kilmer would show up on days they didn’t work to see what De Niro was doing. For the film’s centrepiece scene, when a cop (Al Pacino) and a robber (De Niro) square off across a restaurant table, Mann ran three cameras because he knew one actor would react so precisely to the other that each take would have its own organic unity, and he didn’t want to miss a breath of it. “The slightest adjustment that Al would make in how he was sitting, Bobby would counter,” Mann says. “How a hand would drop to his knee, how he’d shift his shoulders. He’s thinking, ‘Is that guy’s hand moving closer to a gun?’ It was almost subconscious but totally driven by character.”

In another scene, De Niro’s character makes a life-altering decision while driving down a Los Angeles freeway. Not only did the moment have to play in a deep but discernable way on the actor’s face, the shift had to happen at the precise moment that his car passed under a viaduct, flooding the frame with light. Though highway shoots are diabolical to set up, “We shot it three different times on three different days,” Mann says. “There was no question that we were going to keep doing it until we got it. Neither of us was going to settle. Once it happened, you totally believed it, and we had it in one take. But get to something that convincing, it has to be exactly right.”

Russell agrees. “De Niro has a God-given authenticity that covers the whole spectrum from horror to heart. He’s unequalled anywhere,” he says. “He’s hugely compassionate, hugely powerful and frightening and hugely heartfelt. There’s only one person who can be like that, and it’s him.”

Frightening? “That’s part of what’s exciting about him,” Russell goes on. “I think things that are worthy of respect are worthy of inspiring fear. It gets your attention and rivets you, and then it can take you to other places, which involve deep emotions and deep love. I would say Robert has a very deep understanding of love. Any fierceness or scariness he has is grounded in love. That is what makes [his work] the most exciting and complicated.” The things De Niro loves, he loves passionately, Russell says, “whether it’s a chair, a piece of music, a coat or another person. Anything he puts his mind to has a meticulous attention to detail that is almost worthy of a Zen monk. He’s very sincere and intense. It’s that intensity that makes him riveting in all these films.”

In Joy, De Niro plays father to the title character, a rising businesswoman played by Jennifer Lawrence. “It’s exciting when they’re in a scene together,” Russell says. “They have the innate ease of natural athletes but they want to do it at the highest possible level. So they’ll try it any number of ways. They both like to surprise each other, which makes it exciting for everyone on set.” During the shoot in Massachusetts, De Niro and Russell spent hours searching for the perfect strawberry shortcake. They never found it, but the search was its own reward.

Everybody — every crew member, every actor — is in awe of De Niro all day long, every single day,” says Nancy Meyers, who wrote and directed September’s comedy The Intern. “But the awe changes over the course of the film. When you begin, it’s, ‘Oh my god, The Godfather, Raging Bull.’ But then it changes to, ‘He’s amazing to work with.’ He’s loose and unimposing. He’s there when you need him. If somebody else has the dialog, he listens better than any actor I’ve worked with. And how, at this point, does the guy still have new colours to show? The fact that he allowed himself to have a twinkly smile on his face — he’s never gone there. There are probably more De Niro smiles in my one movie than in his last 50 films. But it wasn’t like I said, ‘Smile at the end of the line.’ He just knew that’s who this guy is.”

In The Intern, De Niro plays the title character, a retiree who goes back to work for an e-tailer (Anne Hathaway). It’s not a spoiler to say that the old dog teaches the kids some classy tricks. “I’d read this interview with Katharine Hepburn where she said she and Spencer Tracy worked well together because he was like a baked potato and she was like an ice cream sundae,” Meyers says. “I think we might have something like that here. Hathaway is so chatty, that boop-boop-boop, and De Niro’s so solid and there. That chemistry—they allowed each other to do their own thing. The best of them came out.”

Meyers has worked with supernovas — Meryl Streep on It’s Complicated, Jack Nicholson on Something’s Gotta Give. “Some can pull their weight in ways that don’t always make it great for me,” she says. “De Niro, never. There was never a tough day from him. Not only that, he defended me when something was going on behind the scenes. He had my back.”

De Niro’s fellow interns are played by a quartet of 20-somethings, mostly fledgling comedians. He spent a lot of time auditioning with them, whichactors of his calibre don’t often do. On set, they could always be found in one corner or other, yukking it up. He sincerely liked them, Meyers says, but it was also an acting choice: “I’m sure he knew that his character is friends with these kids, so he became friends with them. He knew that would keep them loose,” which would help the movie. “But he’s never going to say, ‘It’s because I’m Robert De Niro, and they’re on their first movie set.'”

De Niro admits that people are nervous when they meet him—”in the beginning, maybe, but that passes.” He doesn’t do any particular thing to put them at ease. “What are you gonna do?” he says. “I don’t give a speech. I don’t go to somebody and say, ‘Son …’ That’s a bad script. Everybody just works their way into it. That’s fine.”

In one madcap scene, the interns race out of a house they’re not supposed to be in. During the shoot, the temperature was 33 degrees, with high humidity. Not only was De Niro the fastest runner—he dashed ahead of the others in every take—but he didn’t perspire. Between takes the young men, who were wearing jeans and T-shirts, would flop into chairs, gasping and dripping, fans blowing them dry. Meanwhile, De Niro, in a wool suit, calmly read. “Why don’t you sweat?” one asked him. De Niro replied, without missing a beat, “Years of practice.”

Lifelong practice. De Niro was born into a family of artists. His mother, Virginia Admiral, was a painter and poet, and his father, Robert De Niro, Sr., was an abstract painter and sculptor. (Both are now deceased.) His parents divorced when De Niro was three and, late in life, his father came out as gay. Last year, De Niro Jr. helped put together a 40-minute HBO documentary about his father’s work, Remembering the Artist: Robert De Niro, Sr.

“I wanted to do a documentary before his contemporaries were gone because they were important for the story,” the actor says. “I wanted it for my kids, my grandkids, and for friends.” For the same reason, he kept his father’s studio intact, “so that my kids and grandkids would know who their grandfather and great-grandfather was, see what he did. Because it’s real, and he has a lot to show for it.”

In the documentary, De Niro’s voice thickens as he confesses that he should have paid more attention to his parents. “They’d want me to do certain things, go to a show,” he says now (in his longest answer of the day). “Later on I did, but when I was very young, I wasn’t interested. Maybe I didn’t like the attention. I know with my kids, they don’t want the attention. I wish I had done the film on him 10 years earlier. And more on my mother. She used to like to talk about family history— blah blah blah. I was so busy it wasn’t a priority for me. But I knew people who were really great, who were documentarians or archivists, who would have got a lot of things down that would have been helpful.” But he didn’t, and that’s it.

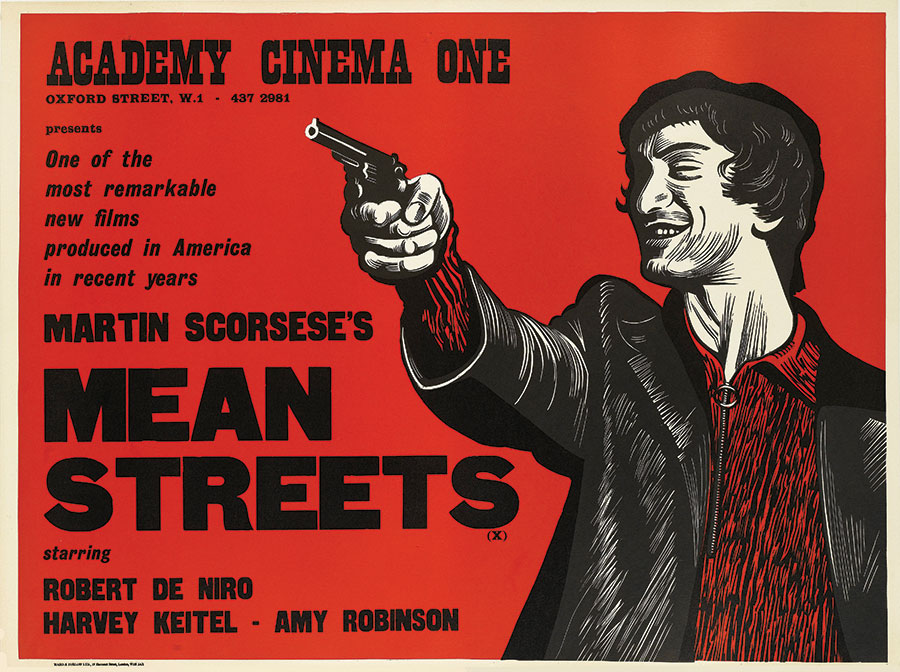

He was busy, that’s true. In 1960s New York, every serious actor studied at either the Stella Adler Conservatory or Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio; De Niro studied at both. After his first collaboration with Scorsese, 1973’s Mean Streets, his career shot to the top and stayed there. He married the actress Diahnne Abbott in 1976, and they divorced in 1988. Along the way they had a son, Raphael; De Niro also adopted Abbot’s daughter, Drena De Niro. He has twin sons from a long relationship with the model Toukie Smith. In 1997, he married the actress Grace Hightower, and they have a son, Elliot, 17, and a daughter, Helen Grace, almost 4. (“She’s a delight,” De Niro says, beaming. “An absolute delight. Every time I see her, I light up. How could you not?”) He also has four grandkids.

I ask a passel of questions about fatherhood: Is De Niro a different kind of father than his father was? Did his parenting change over time, given how spread out his children are in age? “That’s kind of personal,” he replies. “I try to keep us all together as a family. Have things to do together. Have everybody have awareness of the family thing, so they look after each other, especially after I’m not around anymore. It’s a fragmented family. But I try my best to keep everybody together.”

Drena De Niro, an actress and singer—she worked with her father in Joy and the upcoming boxing film Hands of Stone (De Niro plays Ray Arcel, legendary trainer to Roberto Duran)—maintains her father’s privacy. “The way he keeps his personal life intact and separate, that’s something I learned from him,” she says. “How important it is that no matter what you’re doing publicly, you have that core of something that you protect. So I never want to be too detailed about our family life. That is the one thing that’s of my own and for my brothers and sister.”

She will say that her childhood household was a bohemian one, full of actors, directors, artists and pets. She remembers Harvey Keitel coming to dinner, and taking a Jacuzzi with Shelley Winters. The family travelled a lot, and she visited her dad on sets, where he was always “very focused.”

“It was a lot of fun,” Drena says. “High-energy stuff going on. My father likes to keep friends and family around him. The people he works with become friends—he doesn’t move through people. It definitely wasn’t the typical family lifestyle, but there was a lot of warmth, fun, craziness.” When she told her dad she wanted to act, he offered “no huge pearls of wisdom,” but he didn’t question it. “He’s a non-judgmental, open-minded person, always accepting of what people feel their paths are,” she says. He did stress, however, that she had to make the commitment and do the work.

One more thing you might not know about Robert De Niro: “He will try any food,” Drena says. “He’ll eat an entire jar of peanut butter with a knife. He’ll try snake. You can get this man to eat anything.”

De Niro is 72, a year older than the age at which his father died, of prostate cancer. The callous way De Niro, Sr. was treated still rankles his son. “The doctor was not a sensitive person and said [things] in a mean way, a crude way, that only helped to exacerbate the fear that my father had of having a prostatectomy,” he says. “I wish I’d been on him more to deal with it. Because he could have been alive today.” De Niro himself had prostate surgery in 2003.

But reaching his dad’s age, that number, has no significance for him. “I never think about it,” De Niro says. “I like to keep busy.” His second act, if that’s what he’s in, has been a stunning one: adding comedy to his resume in his 50s (including two Analyze This films and three Fockers); starting a film and television company, Tribeca Productions, in 1989; launching the Tribeca Film Festival, which draws three million people annually; co-creating the Manhattan restaurants Nobu (now an international franchise) and the Tribeca Grill; co-owning the Tribeca Grand Hotel and building the Greenwich Hotel, whose East-meets-England library bar became an instant celebrity refuge (I recently saw Jennifer Connelly and Paul Bettany there).

I ask De Niro why he branched out so much. “I wanted to do an addition to the Tribeca Film Center, but it wasn’t financially viable,” he replies, shrugging. “I bought the land next to me, a parking lot, and found a partner who does boutique hotels.”

“I was wondering more about the feeling behind it,” I say. “Was it to stay relevant?”

He snorts. A get-a-load-of-this grin flits across his face. “Not to stay relevant,” he says flatly. “Just to do what I want to do. I see an opportunity, I say, ‘Let’s take advantage of it.’ Relevant.” He snorts again. “No. I always say, ‘If you don’t go, you’ll never know.'”

As an actor, De Niro’s list of upcoming films never ends (currently, it includes an action-drama, Bus 657, and a raunchy comedy, Dirty Grandpa, opposite Zac Ephron), and he has no plans to quit. “What else am I gonna do?” he scoffs. It has been 20 years, however, since he’s worked with Scorsese—does he ever feel a pang that Leonardo DiCaprio seems to be the director’s new muse? “No,” he replies, with another secret smile. “Marty loves Leo, and Leo loves him. It’s a great relationship. They work together, they’re happy, and Leo can help him get his movies made. Hopefully, one day the three of us will do something. That’s okay.”

He almost-but-not-quite laughs aloud when I refer to DiCaprio, with whom he worked in 1993’s This Boy’s Life, as middle-aged (he’s 40). “Leo’s middle-aged now?” he chokes out. “Is that what you’re saying? Jesus. He’s young.”

De Niro doesn’t think about his age. “I feel young in many ways,” he says. “You hear this from people getting older, they feel young, they don’t feel any different, da da da. That’s true for me.” (Please note, however, that the entire time he’s saying that, he’s rolling his eyes.) He doesn’t want to reflect on career highs or share favourite moments. He doesn’t care to ruminate on how New York has changed. “People ask me, ‘How was it back then?'” he says. “That doesn’t matter. New York is what it is now, take it or leave it. This is the reality, right here.”

He doesn’t want to ponder what he knows now that he wished he knew when he was younger. “Oh, I made a big deal about certain things,” he says, waving one hand. “I wish I could have had the foresight to know that they would pass and not matter in 10 years; to let them go and not waste my energy on them.” He won’t name even one of those things: “That’s personal. It’s just, you put a tremendous amount of energy and emotional energy into something, and then you look back and say, ‘What did it matter? What did it mean?'”

He simply won’t waste time on that. “You can look back with nostalgia about certain things, how they were, appreciate what they were,” he says. “But that’s then. I’m here now. It’s not my attempt to feel young. That’s just the way I feel. I have a lot of great things in my past I can be nostalgic about, and there are times I can do that. But basically, I’m thinking about moving forward.”

De Niro doesn’t say much. He doesn’t have to. He has his family and his friends. They know him. To everyone else, he gives his work. That’s it. And it’s more than enough.

A version of this article appeared in the October 2015 issue with the headline, “You Talkin’ To Me?” p. 56-61.

RELATED: