The Guy in Shades: Corey Hart On the Importance of Family and His Return to The Spotlight

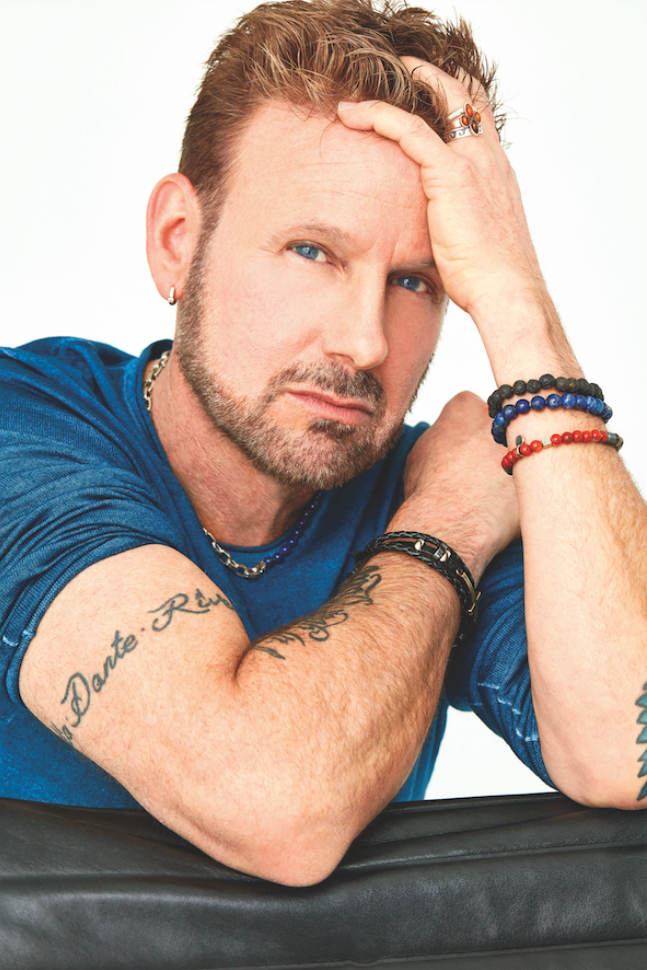

Photo: Chris Chapman

After a rush of success and fame that helped define Canadian pop dominance in the ’80s, Corey Hart shunned the spotlight to raise his family. Now with new music and a national tour, the star is back.

For the record, I don’t believe in time travel, UFOs or that you can’t wear skinny jeans after 50. Yet the moment I replayed “Sunglasses at Night” for the first time in more than a decade, I was transported to the ’80s. That’s the power of music, which, like the fragrance of a long-forgotten perfume, can in an instant snap us back to another era, another place.

I was 16 when Corey Hart’s First Offense album hit the airwaves in 1983. And, like countless other teenage girls at the time, when I saw the video for “Sunglasses” in the summer of 1984, I was crushing hard on the Canadian singer-songwriter. He was my generation’s homegrown James Dean, complete with intense gaze and all the pouting broodiness that the image conjures. But layered on top of his bad-boy appeal was an immense vocal range and emotionally searing lyrics. This bad boy felt things and wasn’t afraid to express them.

But now I’m on set at an east-end Toronto photography studio waiting for Hart to arrive. He’s driving into the city from London, Ont., where during the previous night’s Juno broadcast he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. He performed two songs live, a new rendition of his mega-hit “Never Surrender” that he created for the occasion and the show-closing “Sunglasses” that had the audience on their feet.

Hart, who turns 57 on May 31, arrives with his wife of 25 years, the Quebec songstress Julie Masse. Masse and the couple’s four children were in the audience as Hart gave his moving acceptance speech, where he thanked the Canadian music industry, his loyal fans and, of course, his family. “When I look over to my children, the most beautiful and the greatest songs that I ever wrote are those four beautiful babies, who are now incredible human beings, adults.”

In the back and forth leading up to this cover shoot, Hart’s team had indicated that he would give us an hour to select wardrobe and an hour to shoot. He gave us four hours and gamely tried on clothes that he knew he’d never wear. But certain items, a gold Saint Laurent jacket, a pair of snakeskin shoes, would pique his interest, and Masse would snap a photo on her phone and send it to their eldest daughter, India, 23, who works as a shoe designer at Sam Edelman in New York. It was clear that this was a close-knit family who not only loved each other but respected each other, too. The couple’s other children are Dante, 21, who coaches tennis to support herself but her aspiration is to pursue a career in songwriting. River, 19, is a tennis champion and attends college in Minnesota where she plays Division 1 on full scholarship. The youngest and only son, Rain, 15, is in Grade 9 with a goal to enter journalism as a TV news anchor.

It’s this family portrait that is the key to understanding the musician’s life and art and why, several years after his stratospheric rise to fame, he all but vanished from the spotlight in 1999.

But first there was that spotlight. Born and raised in Montreal, Hart was the youngest of five children. His parents, Robert and Mina, did not have a happy marriage, and they separated when he was 10. In his memoir, Chasing the Sun, Hart wrote, “The trajectory of my journey was very much sculpted by my father and the choices he made.” In revealing passages, Hart discusses his father’s substance addictions, his appetite for prostitutes and the fact that he only came to one of his son’s concerts but also adds that his father “was not a malicious, cruel man.” Still, that emotional abandonment — Hart Sr. did provide financially for the family — would inject his youngest son with the passion and pathos to pour into songs.

The ’80s was the golden era of pop music. The second front of the British Invasion arrived with New Wave bands such as Duran Duran, Culture Club and Spandau Ballet. Stateside, Michael Jackson and Prince battled for domination. Rock bands like U2, Bon Jovi and Mötley Crüe packed stadiums. Everywhere, no matter the genre, young, predominately female fans danced and posed in teased hair, torn sweatshirts and acid-washed jeans. In Canada, 1983 proved fertile with the release of Hart’s debut effort.

“It wasn’t all that unusual for Canadian acts to have pop hits in the U.S. Loverboy was very big just a few years earlier. But they didn’t have a single as big as ‘Never Surrender,’ which was No. 3 in the U.S. and Bryan Adams’s ‘Run to You’ was No. 6,” explains music critic Michael Barclay, author of The Never-Ending Present: The Story of Gord Downie and the Tragically Hip.

“Corey Hart was the first Canadian artist ever to go diamond, meaning selling one million copies of a single album. Adams followed quickly behind,” he says. “Those two shattered the glass ceiling and were the first true Canadian superstars. To this day, only 25 Canadian albums have ever gone diamond. They both had a huge teen audience, but their songs appealed to rock fans of all ages.”

Hart’s first single “Sunglasses at Night” and its accompanying video was an MTV and MuchMusic sensation and catapulted the 22-year-old to international stardom. In the video, Hart wears a white shirt, black jeans and Ray-Ban Wayfarers, as models with lacquer-red lips wear police uniforms and the same shades, giving it the edgy, glossy vibe of a Helmut Newton fashion shoot.

Laurie Brown, music journalist and creator of the Pondercast podcast, remembers the video well not only because she was co-host of The New Music in 1984 but also because she appears in it. “At the time, I was also acting and singing on TV and on stage. I got an audition call for a ‘music video’ from my agent who really didn’t know what the job was about,” Brown explains. “I got the job and was told to show up at the Don Jail and bring some sunglasses!”

You can easily spot Brown as the female police officer in the video. “I remember hearing [the song] a trillion times that night as we filmed the video and thinking this could really do very very well,” she says. “It was so well-produced and super catchy. At The New Music and later at MuchMusic, I recognized his skill as a pop songwriter – he is such a precise and concise writer — everything you hear is considered and essential and packs a punch.”

I had my own brush with a Hart video. In 1986, the video for “Eurasian Eyes” off Hart’s sophomore album, Boy in the Box, was filmed north of Toronto at a horse farm. I was one of the teenage girls who rode at the farm, and a few of us were selected to be horse wranglers. We all tried to act cool as the superstar arrived and did his thing with the crew. But none of us were cool. We wanted to get close to the pop star, to engage and express how his songs impacted us. But the powers that be weren’t going to allow that to happen (no doubt out of fear we’d go all Beatlemania and tear his shirt off). Instead, we each received a signed 8 by 10 of Hart. Mine read, “To Kim, Corey Hart, ’86.” I kept the photo. It seemed surreal that 33 years later, I’m hanging out with Hart on set, having that easy camaraderie that is a natural vibe of the best shoots. I pull out the photo and hand it to him. He’s visibly touched, no doubt the image bringing his own time-travel moment to him. “Oh, you didn’t tear it up,” he says with a smile, then hugs me. And there it is — 1986 all over again.

Over the course of his career, Hart sold more than 16 million records worldwide and amassed nine consecutive U.S. Billboard Top 40 Hits and 32 Top 40 Singles in Canada (including 12 Top 10 Hits). Grammy-nominated, he’s also a multiple Juno and Quebec ADISQ award winner.

That’s a lot of money, fame and accolades to walk away from, but walk he did. And his absence was noted in some snarky corners of the music biz. I read him a quote from Rolling Stone when we sit down for our post-shoot interview. It’s a list the music bible published called 100 Best Singles of 1984: Pop’s Greatest Year. “Sunglasses at Night” is rated No. 100. “[Hart] demonstrated a keen knack for dodging success, turning down Spielberg’s offer to screen test for the role of Marty McFly and passing on an invite to record ‘Danger Zone’ for the Top Gun soundtrack.”

He smiles at the jab. “I’m stubborn. I make bad decisions sometimes.” He adds, “But there is no such thing as a perfect formula for all this. You just try your best. You’ve got to be true to yourself and you’ve got to have pride in what you do, work hard at your craft.”

In the intervening years, as he and Masse raised their children in the Bahamas, Hart wrote and produced several songs for fellow Montrealer Céline Dion. He was also offered a record label partnership with Warner Music Canada (his current label), called Siena Records, which he used to cultivate young artists. “It kept an arm in the music business, but an arm isn’t the whole body,” he says. “As a singer-songwriter, I was retired and as a touring artist, I was retired. I mean, if you’ve only put out a record once in 20 years, can you consider yourself an active artist?”

But the urge to be a devoted full-time father was innate, given his own experiences. “I didn’t grow up having a dad in my life who I knew, who raised me and who was present in my life, so that was a pain that I carried with me.” When Hart’s daughter River was born — his third child in four years — he made the decision to step away from music to be the father he never had.

Hart says of his relationship with his father, “I made peace with myself over it. There’s nothing to gain in life by carrying bitterness or pain.” Robert Hart passed away in 2003.

On the opposite side of the spectrum was his mother, Mina, whom he cherished as a child and adult. “She’d come in and listen to me. I know she’s my mum — I was the youngest of five kids — she was going through a hard time because my parents had split up at that point. So I thought she channelled a lot of her hurt energy into me and into being there for me and supporting me and trying to encourage me.”

Mina taught her son about unconditional love, and catching a glimpse of how his children interact with him is legitimately moving. His daughter River, the tennis champ, was texting him as we spoke. He waited until our interview was over and showed me the texts. River had flown out of Toronto that day and come down with a stomach bug and was reaching out to her father to fix the problem — Gravol — and also for the comfort of her dad when she’s far from home and sick. It was an intimate moment between father and daughter. “If I hadn’t been there for my children all these years, this wouldn’t have happened,” he says proudly.

Given how passionate Hart feels about his family it would take some pretty persuasive power to get him to step back into his old life. That persuasive power came in the form of legendary Canadian music producer Bob Ezrin, who has worked with the likes of Alice Cooper, Pink Floyd and Kiss among others. The singer-songwriter and Ezrin had never met until they were seated at adjacent tables at a fundraising event for Canada’s Walk of Fame in 2017, the year after Hart was inducted. After Hart performed, Ezrin approached him. “I completely understood his stay-at-home dad approach to parenting, and I admired him for it,” Ezrin explains. “But we were really impressed with the power of his presence and voice and how much the room loved him. I thought, ‘This guy is a real star! He needs to get back out there.’ I started with his kids (of course) and told them I thought he was amazing and should be performing. They agreed completely. So there was my licence to kibitz,” he recalls.

Ezrin went to the Bahamas for more talks but didn’t get a firm commitment. Then one afternoon, Hart called him to say that he’d started the ball rolling and was going to go back out and tour, but before that he wanted to release new music. “He said he would go back in the studio if I would produce it,” Ezrin explains. “Honestly, I was really hoping to take that time off myself after a very busy few years, but Corey is very hard to say no to. So we agreed to move forward with an EP. I did tell him to be careful what he wished for!”

The result is Dreaming Time Again, which was released in May and is Hart’s first collection of new studio music in more than 20 years. This summer his Never Surrender Tour kicks off on his birthday (May 31) in St. John’s, Nfld., making it his first major arena tour since 1986. It should come as no surprise that the songs on the new album are very autobiographical, about his life in the last two decades and how he feels in the present day. So there’s a song written for Julie, there’s a song he wrote for his mom and one for his daughter, India.

One of the other tracks is “First Rodeo,” and Blue Rodeo’s Jim Cuddy sings on it. The idea for the collaboration came from a fan on Hart’s Facebook page. The fan had always declared that Hart was her No.1, Cuddy was No. 2. Then she attended a Cuddy concert and posed with the singer and posted it on Hart’s page. “There was a picture of her with Jim, and he’s got a little sign in front of him that read ‘I think I’m moving up to No. 1’ or something like that, with a big smile on his face,” Hart laughs. “And then she writes at the end, ‘My ideal would actually be to have you two guys do something together because your voices together would be, like, off-the-charts cool.’”

Hart agreed and called up Cuddy, and they recorded the song. “I always thought he was a great singer. Meeting Corey and getting to know Corey gives you a whole new perspective of his music and gives you a deeper appreciation of his songs,” Cuddy writes in an email. “I always recognized his hits, and that was really consolidated when somebody covered ‘Sunglasses at Night’ at the Juno Cup Jam. A hit is a hit is a hit, no matter who does it.” Cuddy will join Hart onstage when in Toronto to perform the new tune.

With the new tour about to commence, it was striking when, before his Canadian Music Hall of Fame induction, he told a red carpet interviewer that he was nervous about performing. So how did he think he did on Juno night? “I think I did okay. I think I could have done better but I think I did okay.”

Understatement and being humble are key Hart traits. Still, any one of the millions of fans who watched his performance unfold live or watched it on YouTube later would never notice any stage jitters. The man was having a blast. “I did have a great time. The audience was incredible,” he says, beaming.

Is it still fun to play “Sunglasses,” the song that made him? “You know what? I should lower the key because I sang it in the original key because I’m a purist and I’m stubborn, so I said, well, that’s the key that I sang it in when I was 19, 20 years old,” he says, laughing. “But as we get older, the voice range changes a little bit, and so most artists lower the key. No one will know the difference, but I would know the difference and I didn’t want to do that. But the key’s just a little too high for me now. So I’ll make it a little lower for the tour. And there’s no shame in that, but it’s part of my stubborn streak. But I’m very proud of my old songs, and I’m proud of what I did. They’re part of my history, for better, for worse.”

Then Hart pauses, thinking of his stubborn perfectionist streak. “I should have never admitted to wanting to lower the key of ‘Sunglasses.’”

Aging is tough on us all. But Hart prefers a positive spin. “I think it’s beautiful to get old. I don’t think it’s beautiful when the body doesn’t feel good anymore, and it’s harder to get up, and it’s harder to do things, and certain things start falling apart,” he says.

Through the years, Hart also coped with severe chronic pain due to a cervical herniated disc, and I ask how he is managing. “I don’t really talk about that. I don’t like to talk about that,” he says. “But I’m going to try my best to get through the tour and, you know, I am a warrior.

“But I love the experience of life, and I love the miles travelled. And I think that if I could live a long life and still have relative good health and watch my kids grow up and have grandkids, I’m going to be such a blessed man.”

During the shoot, watching Masse and Hart interact on set, speaking to each other in French, deciding what outfit looks good and what isn’t really “him” was a lesson in how a marriage can be a true partnership. I ask him what the secret was? He smiles. “That’s a great question. The key for us is that we both respect each other. We trust each other. And obviously there’s the physical attraction and all those things, but we also share core values.” He adds that they had their first child within the first year they were together.

“Falling in love so quickly, both being in previous relationships and then suddenly having this great thing that, if you look at it on paper, doesn’t look like it’s going to last. But paper’s not always right.”

If the lyrics to his songs could be interpreted as wearing his heart on his sleeves, the tattoos that decorate Hart’s arms are a literal canvas of his love for his family. “They are an essential part of my body-soul experience – spiritual and physical,” he says. “I started with my very first about 25 years ago and, unlike heaps of clothes accumulated over the years, not one of my tattoos do I regret.”

He has the name of his children in a band around his right arm, the word “freedom” written in both French (liberté) and in Cyrillic (svaboda) because his grandfather was Ukrainian of Russian descent. On the very same day his beloved mother died in 2014, he took her signature and tattooed a bracelet around his left arm with it. There’s also a guardian angel, dragonflies for Julie and every child with stars. Perhaps his favourite is a beautiful winged bird that his daughter India drew for him.

It’s no wonder then, that this year’s Junos was a full circle moment for Hart. After all, he met Masse at the 1993 ceremony when they co-presented an award, and this year she performed as a backup singer during his performance, making his Canadian Music Hall of Fame induction the perfect intersection of stardom, music and family for the “guy in shades.”

So what’s next after this album and tour?

Hart smiles wryly. “I think my goal is to have Rolling Stone retract that quote and say that Corey Hart, in the ninth inning, he came in and hit a grand slam. How about that?”

A version of this article appeared in the June 2019 issue with the headline, “The Guy in Shades” p. 29-39.