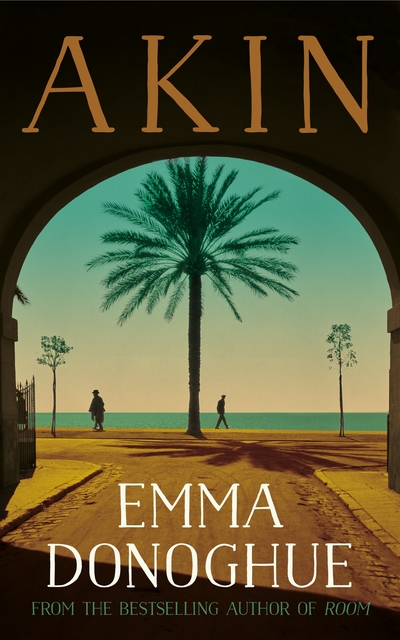

Author Emma Donoghue on Exploring Family History and Aging in Her New Novel “Akin”

Photo: Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

The Irish-born novelist Emma Donoghue (Frog Music, The Wonder) is a multi-hyphenate—in addition to being a literary historian and playwright she’s an Academy Award-nominated screenwriter, for the adaptation of her own acclaimed 2010 novel Room.

This fall and for the first time since Room, Donoghue returns to a contemporary setting with her new novel Akin. Although the past isn’t entirely left behind: the story follows Michael, an orphaned 11-year-old thrust into the care of his great-uncle Noah, a retired professor he’s never met. Together this odd couple embarks on a research trip to Nice and try to reconstruct the lost years of Noah’s mother, who stayed behind during the Nazi occupation of France to care for her ailing father, a famous photographer named Père Sonne.

As their detective work is complicated by a cache of anonymous old photographs and vague childhood memories, it’s a story about World War II and the awful ambiguity of wondering what relatives did during the Occupation, but also about finding unlikely common ground across generations. The novel was inspired in part by time Donoghue spent living in France with her family (in all, two years over the past decade) so, “not just the history of Nice but all its sort of trashy modern touristy side,” the author explains with a chuckle. From her home in London, Ontario ahead of Akin’s fall book tour, Donoghue shares some of the background of her new novel.

Nathalie Atkinson: The book opens with Noah, a reluctant retiree who is turning 80, and his internal monologue of mixed feelings about that. And throughout the novel he enumerates the ways he’s patronized and condescended to because of his age—

Emma Donoghue: And he does plenty of condescending himself too! [she laughs] ’I may not walk fast but I’m despising your micro-shorts’ sort of thing.

NA: There is quite an age difference between Noah and his great-nephew Michael—69 years. What were you hoping to explore with that gap?

ED: With this book I took a lot of pleasure in working out both the strengths and weaknesses of being old and being young. Specifically of being Noah’s generation and Michael’s. I know, for instance, kids teach themselves things on the internet a lot, they’re quite empowered by it because children used to have to rely on their adults to explain things. And I tried not to make Noah too “old”—he’s fairly comfortable with technology, he’s fairly mobile. I wanted to suggest that energetic, un-aging person inside the older body. I gave him a few aches and a few naps to make it realistic but didn’t want to stereotype him as old in the way that so many books and films still do.

NA: Do you think that aging and how the elderly are treated and perceived, is changing?

ED: I think there’s been such a change in how people who are older present themselves. They don’t send out that Little Old Man or Little Old Lady vibe simply because of getting to a set age. People inhabit that active middle zone for so much longer. If we made Cocoon now they’d all have to be 100!

NA: From the resistance to give up a telephone landline to kids who stubbornly won’t eat anything but junk food, it feels like you enjoyed peppering the story with amusing moments of commentary and social observation.

ED: I love writing historical fiction but I have to say, with contemporary fiction you get to put in everything that’s in the back of your mind. It’s a great way to throw in things that have occurred to you. The funny thing about Noah is obviously he’s like my dad in that he’s older and he’s a New York professor. But really I think Noah is me because I’m horribly educational with my kids—they can’t look at something without me making some observation about cumulus clouds or World War Two, especially in France. Every time I’d read one of those little plaques I’d be, Oh children, brave resistance fighters were hanged here!

Sometimes it was just incongruous, we’d be having a lovely time in the sunshine licking ice cream and I’d start telling these heartbreaking stories. I can’t seem to resist that impulse to educate.

NA: Accordingly, you used several strands of historical inspiration for the milieu, including European photographers of a certain era. Was there any one in particular?

ED: I steeped myself in the photography of roughly 1900 to 1940. But I didn’t want Père Sonne to seem like a thinly-disguised version of Robert Doisneau or Robert Capa or any one of them so I did a lot of studying individual photographs, and that particular generation of Hungarian photographers, with their noms de plume—like Brassaï.

NA: How does Henri Matisse’s daughter Marguerite fit in?

ED: What I found intriguing about her was that she was this perfect helper, this ideal artist daughter. And then the idea that she suddenly got caught up in politics, in her 40s when the war broke out, I found that absolutely intriguing—the idea that the war would have given this very meek woman suddenly a life of her own.

NA: Whether from trauma or from discretion, members of clandestine Jewish resistance groups were still reticent decades later about sharing details of the work they had done, even with family.

ED: It’s very interesting, isn’t it? So many people did line up and either demand medals that, yes, they had earned or demand medals that they hadn’t earned at all. Some of the bravest people just always played it down. A lot of them had such a lingering pain about all of those who weren’t saved.

NA: In the acknowledgements you thank your mother-in-law. What was her role in your process?

ED: She’s French and grew up in the North, the bit that the Nazis directly invaded and had to cross over between the two zones. They hired a smuggler guide to get her to the other zone. She’s definitely the only person I know who was in France in the war and she’s always talked about how her relatives were a mixed bag in terms of their loyalties. Probably it was from talking to her as well that I got interested in the ambiguities in France under the war. Movies tend to show it as brave French and evil Nazis and it was always more complicated than that.

NA: And it is so polarizing.

ED: Because in a way people fictionalize their own lives, you know? So many people claimed to be involved in the Resistance and it just wasn’t true. And then a larger percentage did really tentative things like read a newspaper. I read This Magazine, but that doesn’t make me part of the progressive activist class in Canada! It’s a passive form.

NA: In the same way as it’s impossible that all the people who now claim to have been at Woodstock or that first Beatles concert to actually have been there.

ED: Or Stonewall. You could say that personal family history is a form of fiction anyway. And of course once the dead are gone we can’t ask them the questions that we so often don’t get around to! I think many people have this sense of their parents lives, but think a certain amount of speculating about the history of our parents is common to all of us.

NA: Does that make the act of going through personal effects all the more poignant? Is that why the trove of old photographs Noah finds have such weight?

ED: I think pre-digital photos still have a kind of nimbus of truth to them. I liked the idea of starting with these images that appear very ordinary and then unpicking them. It’s the idea that a photograph, even if it’s not obviously an artwork, could contain some kind of evidentiary power. That it probably wasn’t messed with.

Akin will be published on September 3 by HarperCollins Canada; Emma Donoghue will be on book tours across Canada throughout the fall.

EXTRAS

NA: What author would you most like to be onstage with?

ED: Neal Stephenson! I read Kryponomicon three times. The thing is I would probably be all tongue-tied and giggling like a schoolgirl because I revere him so much. And he’s so brilliant he could do all the talking. Maybe that would be my goal, to ask him interesting questions.

NA: In the past you’ve mentioned Emily Dickinson and Angela Carter as favourite authors. What book do you most often give as a gift?

ED: I have given the Philip Pullman His Dark Materials trilogy to several people. I’m currently reading it to my daughter so it’s thrilling to experience it again line by line. When she Marie Kondos her drawers, for example, it’s very time-consuming so she’ll summon me as a kind of human audiobook to read to her as she tidies.

NA: That’s a clever way to entice her to keep her room clean.

ED: You have great conversations when you read books aloud because things come up. Especially reading her older books — we had a breakthrough adult book recently I read her Pride and Prejudice. To parse all the subtleties of snobbery in Jane Austen’s day and why certain things are okay for certain people in the village but not for others…oh, it’s a complicated social world.

NA: Moving beyond books, what’s your binge-watch TV recommendation?

ED: Gentleman Jack. [My partner] Chris and I are both big Anne Lister fans—I did my first play about her in a student production back in 1991 and I gave a paper then from that was asked to write my first non-fiction book. We’ve been together to see her diaries in Halifax. So to see Anne Lister finally getting her moment in the sun via Gentleman Jack, I’m just so happy.

NA: I am a superfan of the series creator Sally Wainwright.

ED: Me too! I’ve seen everything she’s done — Happy Valley, Scott & Bailey… What’s great is that Gentleman Jack is also very funny. She’s very cleverly managed to choose material from the diaries—sometimes I recognize specific passages—and yet she shapes them much more dramatically, all somehow reworked to make a gripping plot. I don’t quite know how she’s managed that, I’m such a newbie as a screenwriter so Sally Wainwright is my absolute hero.