Author Linden MacIntyre on Storytelling and the Intersection Between Journalism and Fiction

Photo: Rick Eglinton/Toronto Star via Getty Images

Aspiring writers and literary fans will get a chance to pick the brain of Canadian author, journalist and broadcaster Linden MacIntyre at the 40th Toronto International Festival of Authors (TIFA) on Nov. 1.

The 76-year-old will take part in a panel discussion with fellow authors Maureen Jennings, Guy Gavriel Kay and Shandi Mitchel.

MacIntyre’s storytelling spans multiple mediums, including a 25-year run hosting the CBC investigative series The Fifth Estate , which earned him 10 Gemini Awards and an International Emmy.

His transition to fiction writing brought similar success, with his second novel, The Bishop’s Man, earning the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Dartmouth Book Award for Fiction and the Canadian Booksellers Association’s Libris Fiction Book of the Year Award.

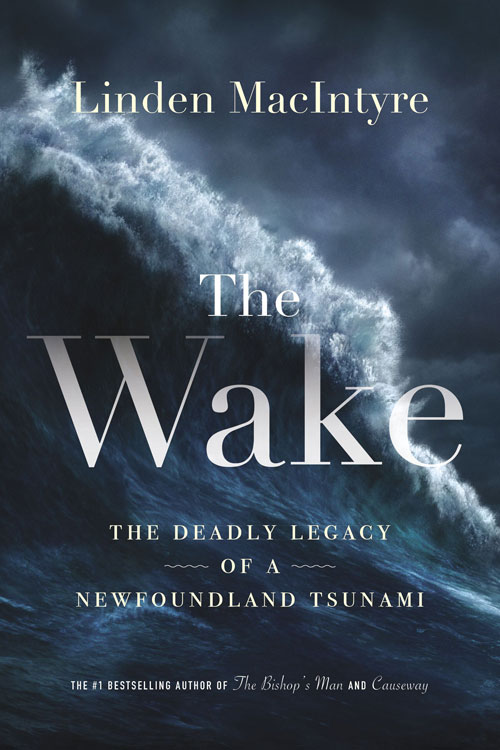

In his most recent book, The Wake, MacIntyre returns to his journalistic roots to explore the aftermath of a tsunami that struck his home province of Newfoundland in 1929.

Ahead of TIFA, Linden MacIntyre took some time to talk to Zoomer about the festival, the dynamic between his work in journalism and fiction, and his new book.

MIKE CRISOLAGO: This year you’re appearing at the Toronto International Festival of Authors in conversation with Maureen Jennings, Guy Gavriel Kay and Shandi Mitchell. What do you enjoy most about participating in TIFA?

LINDEN MACINTYRE: Public conversations with other authors tend to expand my understanding of what is normal, or universal, in the way writers approach their work, subjects; how we regard technique; how we react subjectively to the challenges of a solitary activity that is usually followed by intense public scrutiny of a created product.

I was recently on a panel with an author from Belgium, one from Tel Aviv, and an Indigenous Canadian, but our stories had common themes and I believe we profit from exchanging insights on storytelling from a variety of personal experiences. Obviously, TIFA provides a rich opportunity for these exchanges.

MC: Often, festival events like TIFA include questions from the audience. What’s the most common question you get asked by readers? What’s the strangest?

LM: I think most questions flow out of a common human impulse to tell stories. And so they tend to reflect a curiosity about a writer’s writing habits, technique, how s/he got started, got published, etc. My most common query has been whether I have a preference for writing fact or fiction. I was 50 years in journalism, much of that time also writing fiction. Did I have a conflict, or was I sometimes in danger of mixing up the genres? My response invariably is that all good fiction is fact based; all writing an exploration of human consciousness and human experience. Journalism nourished my imagination.

MC: Given you’re appearing at a festival of authors, which authors do you get excited to see in conversation and why?

LM: Every public, literary conversation has the potential to excite or to inspire, or to induce numbness, fatigue. Famous writers are often self-absorbed and self-referential answers are of little value to an audience made up of people who are interested in gaining universal insights into stories and storytelling. And so I’m less interested in the author than in the subject matter that a good interviewer will explore with an author or group of them.

MC: If you could book your own fantasy festival of authors, which authors, living or dead, would you have at your fest and why?

LM: I would have enjoyed watching someone trying to interview James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway and Brendan Behan on the same stage.

MC: You’ve said of your latest book, The Wake, that the story has been with you your whole life and you wish you’d started writing it in the 1980s. What advice would you give to others who’ve spent much of their lives with a story that they’ve always wanted to write but aren’t sure how to get started?

LM: I believe the important part of writing is a process that goes on inside the

author’s head and, in many cases, for a very long time. I would like to have started writing the book more than 50 years ago when my father was still alive. But I wouldn’t have known how to do it, because I didn’t understand the full significance of what I was hearing and seeing around me. I didn’t understand the importance of discipline and technique in the creative process. I still didn’t understand that the passage of time enriches our experience and improves perspective. How we gain understanding from experience and broadening perspective.

I think a storyteller is gifted/cursed by a tendency to pay attention to everything experienced, to the smallest details of external and interior nuance — what one sees, thinks, feels as we acquire experience. At some point, the words will form and join together and deliver a considered account of our experiences and insights. So while I didn’t start to physically write the book when the experience was closer, I can see now that the creative process started long, long ago, and the writing started when it could and should have.

Click here for more information on the 40th Toronto International Festival of Authors.

RELATED:

Linwood Barclay Talks Stephen King, Killer Cars and Writerly Advice

Q&A with Joan Thomas, Winner of the 2019 Governor General’s Literary Award for Her Novel Five Wives