Monty Python Great John Cleese on Humour, Healing and His One-Man Show ‘Why There Is No Hope’

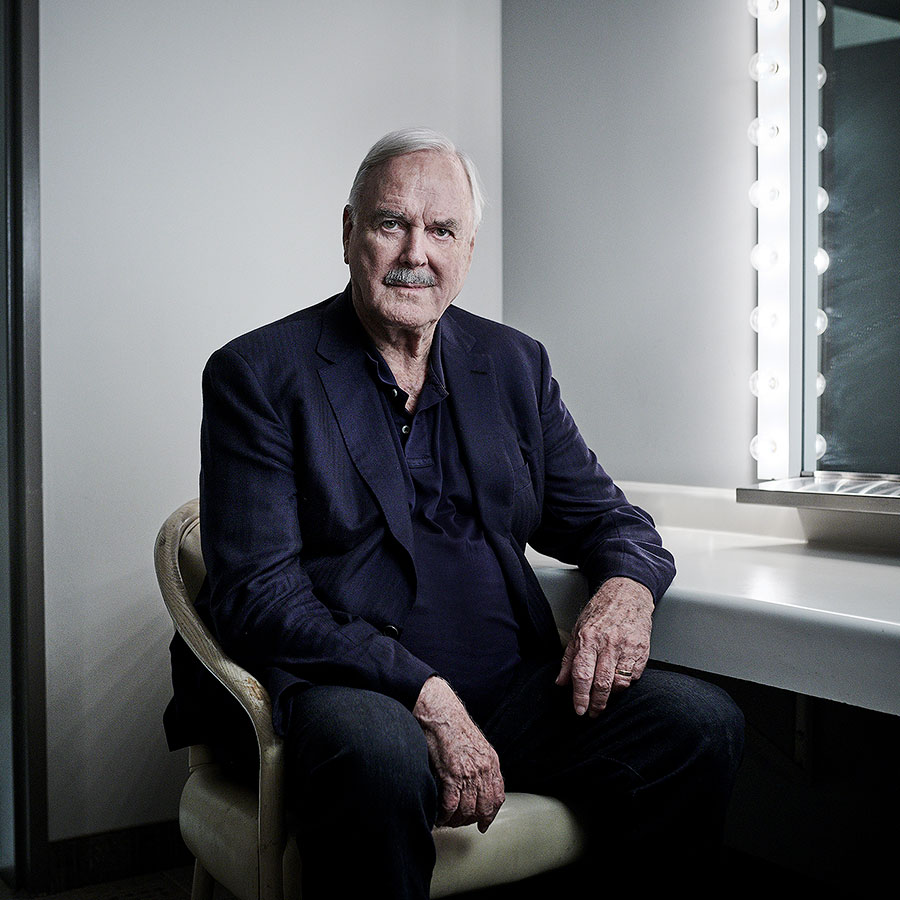

John Cleese appears on Aug. 2 in a live, international livestream broadcast of his one-man show "Why There Is No Hope." Photo: Courtesy of John Cleese

John Cleese is in a good mood, all things considered. In fact, to borrow a Monty Python line, you might say he’s embraced the mantra: “Always look on the bright side of life.”

In late July, en route to Toronto to prep for the upcoming international live stream of his one-man show Why There Is No Hope at Roy Thomson Hall, the 80-year-old Monty Python alum learned the gig was postponed. But the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic made making arrangements to return to the U.K. difficult. So when we spoke for a recent interview, he was temporarily stranded in a hotel in Ann Arbor, Mich., trapped between Toronto and home.

“I think the advantage of growing old is that you realize that very few things in life really matter. And most things don’t matter at all. And once that seeps through … into your sort of being, that helps a lot,” the comedy legend says over the phone when I ask how he’s holding up. “Because even when everything goes wrong, like the last three or four days with all the [travel] arrangements I’ve been trying to make, I just say to myself, ‘It doesn’t really matter.’ I mean, they’re only inconveniences. Nothing worse than that.”

It’s a level of Zen in the face of frustration that one might not expect from someone promoting a show called Why There Is No Hope. But that’s the point. While Cleese’s thesis refers to the limitations the collective society possesses for finding happiness, he believes that the possibilities for personal happiness and fulfillment are endless.

“So if you say, ‘Right at the moment, there’s not a lot we can do about the extraordinary state of the world,’” he explains, “what you can do is you can help people. Like my daughter recently helped a former teacher of hers, a lovely woman who’d fallen into a depression because of the death of her 14-year-old son. And we were able to arrange treatment … So that’s something we could do.”

He adds that at this point in his life he’s the happiest he has ever been, crediting his current wife, jewelry designer Jennifer Wade, 48 (“fourth time lucky,” the thrice-divorced comedian quips), and his two daughters for his state of bliss. He also points to the Serenity Prayer — God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can and wisdom to know the difference — as a road map to personal fulfilment.

And doing a one-man comedy show like Why There Is No Hope — which is now being streamed live from London’s Cadogan Hall — offers Cleese an opportunity to help others in perhaps the best way he knows how: through humour.

In fact, it’s not a stretch to say that Cleese believes in the healing power of laughter. He notes that his views on the importance of comedy, particularly in times of turmoil, “have changed enormously because, don’t forget, I’m very, very old.”

He explains that, when he attended Cambridge University in the 1960s, “there was popular entertainment and high art. There was a very clear boundary between what was okay for an intellectual to like and what wasn’t. I can still remember the great fuss when the Times of London actually reviewed a Beatles concert.” As a result, he thought of comedy as a luxury. “And then I began to realize, over the years, it’s actually much more important than that.”

Cleese points to a film festival he attended in Sarajevo as a watershed moment for his perception of comedy. While there, people told him about the horrors and the toll the Bosnian War inflicted on the city in the mid-’90s and how, during that time, some of the residents converted an underground garage into a makeshift movie theatre and screened comedy films, with a focus on Monty Python. And even though it didn’t change anything about their situation in the war, they told Cleese that comedy offered attendees a temporary reprieve from the reality of their daily lives and actually made them feel better.

“And I think it’s more than just a temporary relief. [Comedy] moves us to a better part of our mind so that we seem to be able to cope with circumstances that are horrible,” he says. “There’s also physiological evidence that laughing actually helps the immune system. But it’s something about [how] it moves us to a point of view. Maybe we just start seeing how completely ridiculous life is.”

To that end, he remembers a friend telling him in Python’s early days that “‘after I watch an episode of Monty Python I simply cannot watch the evening news ’cause I can’t take it seriously.’”

Cleese adds, “And I think that’s very healthy.”

The Absurdity of Life

Of course, playing on absurdity is a Monty Python hallmark. And with last year marking the group’s 50th anniversary, Cleese notes that it “astonishes” him that people still love the troupe’s comedy and that new generations of fans continue to emerge.

“I think that the thing about Python is just that — it reminds us of the silliness of life.”

Cleese points to a sketch like the famed Fish Slapping Dance in which he and fellow Python Michael Palin face each other and dance on the side of a canal while slapping each other in the face with fish.

“That still reduces people to tears. If you said, ‘Well, what does it mean?’”

Cleese lets out a hardy laugh.

He then recalls the scene in Life of Brian — the 1979 Python comedy about an ordinary man named Brian who lives in Biblical times and is mistaken for the Messiah — when the titular character explains to his religious followers that they don’t need to worship him and that they’re all individuals.

“And they say, ‘Yes, we’re all individuals.’ And one man says, ‘I’m not,’” Cleese says. “You can’t figure out what that means. It makes no sense and it’s extraordinarily funny. So sometimes the funniest things are almost the silliest. You don’t get this kind of healing laughter from witticisms.”

Though Monty Python endures, Cleese’s ideas on the use of humour aren’t universally agreed upon. In June, the comedian clashed with BBC executives and social media users over an episode of Fawlty Towers, the 1970s hit comedy series, which Cleese co-created and starred in with his first wife, actress and comedian Connie Booth. The BBC announced that they were temporarily removing a 1975 episode of the show called “The Germans” from its UKTV streaming service because it contained racist remarks from a regular character called Major Gowen. At the time, Cleese objected to the episode’s removal, calling it a “stupid” decision and claiming that the show was anti-racist and “not supporting [Gowen’s] views, we were making fun of them.”

His stance drew some ire, including from people on social media — particularly Twitter, where Cleese remains active. Another belief that tends to prove controversial is his long-time stance of opposing “political correctness.”

“I’m afraid my opinion … is that it started out as a good idea, which is ‘Let’s not be mean to people’ and then it’s just become something that’s really quite harmful.”

He adds that his objection to political correctness stems from his belief that, “all humour is critical. You can’t laugh or make fun of someone who’s perfect. It doesn’t work that way. It’s failings, human failings, that are funny. It’s not things going right. It’s things going wrong.”

That said, he’s willing to engage in debate on social media. “I also know that if someone has a go at me, I’ll have a go back. I don’t think I have to be polite to someone who’s rude to me. If somebody is critical, that’s quite different. If they do it politely, then it becomes interesting.”

The Future Is Fishy

Near the end of our interview, Cleese receives a call from his wife.

“Tell Mike that you’re a silly woman,” he says playfully, putting Wade on speaker phone before adding, “She’s made me happier than anyone else ever did.” He refers to her as “Fish” because, as he says, “she swims like a fish, and it’s quite beautiful to watch.”

But there’s another fish in Cleese’s life at the moment — one called Wanda. Cleese revealed that he spent part of his pandemic isolation writing a musical adaptation of A Fish Called Wanda — the 1988 hit comedy film he wrote and co-starred in — with his daughter, stand-up comedian Camilla Cleese. “To my great delight, John Du Prez, who wrote the original music for Wanda likes the lyrics and he’s written some very funny music. And so I’m very optimistic about that.”

Like everyone else, though, 2020 has also thrown Cleese a few curve balls — and not just when it comes to his travel plans. Last Christmas, the comedian told his wife that 2020 would be the year he started to get in shape. In January, though, he had a bone spur removed from his toe; in March, a bladder cancer scare led to more tests (everything, thankfully, was fine); and then in June, he had a cancerous tissue removed from his left leg.

And yet, once again, humour helped lighten the weight of the situation, though this time Cleese was on the receiving end.

The comedian laughs as he recalls his surgeon quoting one of Cleese’s own lines from the famous Black Knight scene in the 1975 film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, where Cleese, as the knight, refuses to concede a battle after having his arms and legs chopped off.

“After he had stitched me up,” Cleese says of the surgeon, “just as he left the room, he said ‘Tis but a scratch.’”

John Cleese’s Why There Is No Hope live-stream special takes place on Sunday, Aug. 2. Click here for the showtime and digital ticket information.

RELATED: