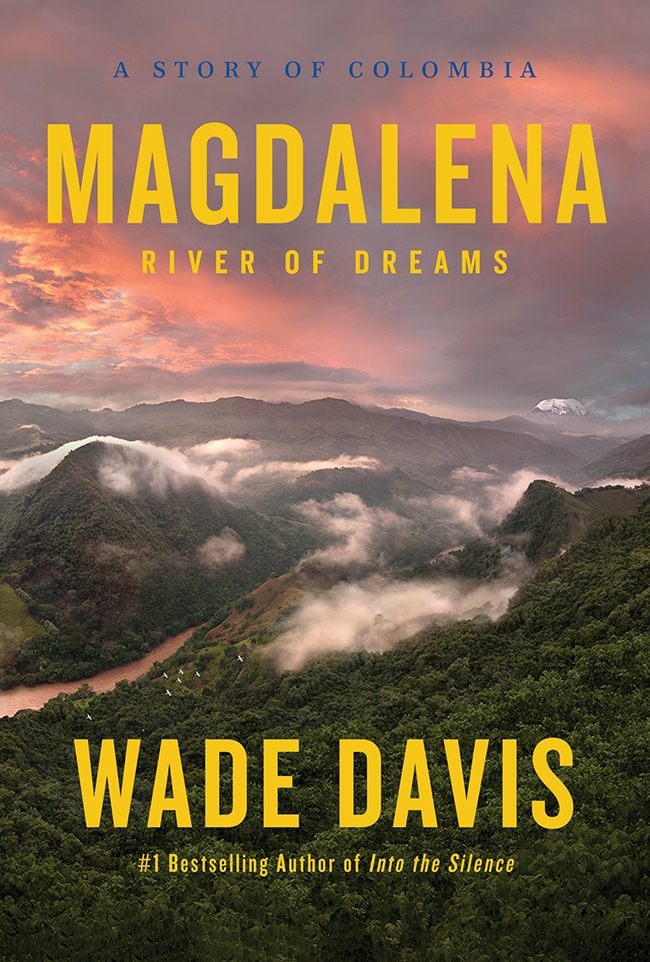

Explorer Wade Davis on His New Book ‘Magdalena’ and Chasing His Destiny Around the World

Wade Davis standing on Hood’s Point on Bowen Island with the shore of Lions Bay in the background. Photo: Chris Chapman

In his latest book, Magdalena, explorer Wade Davis revisits the Colombian river that stole his heart 50 years ago and reimagines its ending. We found him at his B.C. home where he shared more stories from his travels.

Rivers run through humanity’s stories in many guises. They are boundaries and passageways, homecomings and leave-takings, life as well as death. For Wade Davis, the explorer, writer, scientist and anthropology professor, the river that is the metaphor for all the others is Colombia’s mighty Magdalena and, to him, it is nothing short of redemption.

It’s a lot to put on a river. But Davis, 66, came of age on Magdalena’s banks. He first set foot in Colombia as a Montreal schoolboy of 14 and, enchanted, took a one-way ticket back six years later to parse the nation’s secrets. Now, as an elder, he has finally surrendered to the seductions of the river. He can see not just what it once meant to its people but also what it could mean. He has laid it out in his latest book, Magdalena, River of Dreams, an ardent divination of healing and hope.

On a summer day, he spent nearly two hours on the phone from his home on Bowen Island, near Vancouver, passionately regaling me with tales of the river and what he prophesies for it.

It was a parable, hanging on choices yet to be made. Magdalena’s waters, long fouled by industry’s toxic compounds and rotting human corpses dumped by illicit drug troops, will run rich and clear. Magdalena will once more take her rightful place at the heart of the country, sweeping away the collective amnesia of Colombians who have long forgotten the river’s power.

And when Magdalena is redeemed, so too will be Colombia itself, the

cocaine-scarred South American nation that, now in precarious peace, was for decades an emblem of brutality and corruption. Forgiveness will follow. The river that never abandoned its people will resurrect them.

“I feel more strongly about this book than anything I’ve ever done,” he tells me.

It is only days later, still savouring the river and the metaphors she carries, that I begin to wonder whether the redemption Magdalena represents is not just for the river and the country he cares for so passionately but also for Davis himself. What if, despite all that he has done in his life, he still needs to do one more thing – shape the future of the river that has been such a key to his past?

Rivers have always been Davis’s conduit, no matter where he has gone. Born in Vancouver, he grew up in Montreal on the banks of the St. Lawrence, one of the many sacred waterways that sculpt the imagination of our country. He was shaped by tales of the coureurs de bois who paddled their canoes from its banks to Canada’s other watery arteries, seeking pelts, money and glory. He hungered to follow in their footsteps, wholly rejecting the buttoned-down job his father, George, held as an investment manager at the Royal Trust Company.

And his mother, Gwendolyn, harboured ferociously ambitious dreams for her son, working a tedious job to pay his private-school fees at Lower Canada College. That first journey to Colombia as a young teen was on the roster of the school’s field trips.

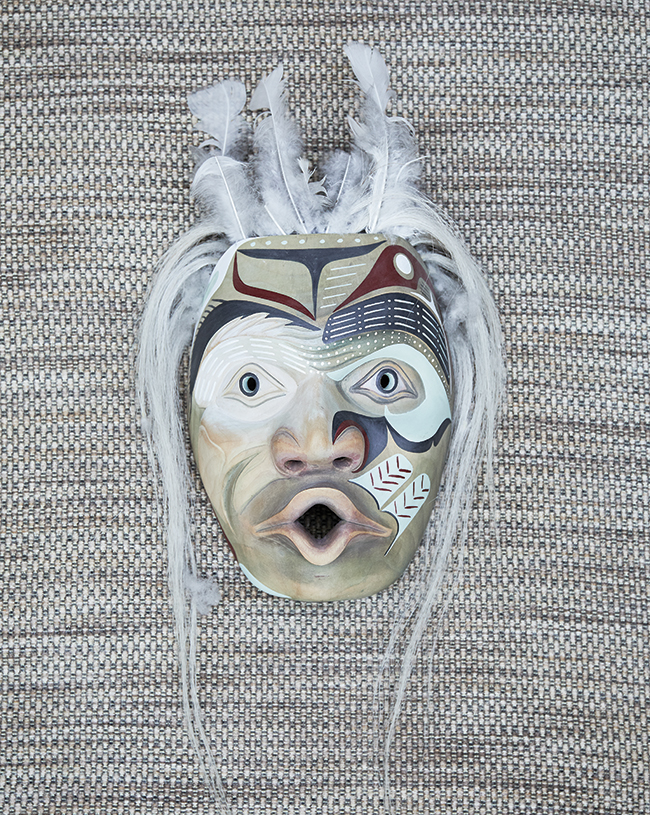

Since then, he has devoured experiences in all corners and many waterways of the world, voraciously scooping up knowledge about plants, cultures and geography and knitting them into compelling tales about the necessity of cultural diversity. The myths and practices of the ancients – including the marine wayfinders of Polynesia and the nomads of the Sahara – and of modern Indigenous peoples are humanity’s greatest wealth, he reckons.

His explorations began with three years of peering at roots and leaves in the Amazon and the Andes for degrees at Harvard University, including a PhD in ethnobotany.

Then he immersed himself in the plants of Haiti and their neuro-pharmacological use in voodoo, which meant struggling to understand the intricate psychology and politics of that tiny Caribbean nation. At one point, in such a fever of amazement at the nighttime religious ceremonies, he failed to realize he had both malaria and hepatitis, he tells me. Once, he set his clothes on fire at a secret ritual to prove his mettle to voodoo leaders, an act of theatre that singed his eyebrows and had them roaring with laughter. All good fun, he says.

He turned his Haitian experiences into the 1986 international bestseller The Serpent and the Rainbow: A Harvard Scientist’s Astonishing Journey into the Secret Societies of Haitian Voodoo, Zombis, and Magic – his first book – which became a 1998 cult horror classic loosely based on his book and directed by Hollywood screammeister Wes Craven. But it wasn’t enough. He was inconsolably restless of mind, body and spirit.

“No one in the world was more ambitious than me,” he says. “Never for fame, never for money but to know my destiny.”

That compulsion to find his fate nearly did him in. “My fire was so bright, so all-consuming that I came very close to self-immolation,” he writes in Magdalena.

He wasn’t suicidal, he tells me, but simply couldn’t sit still. He lived to work but didn’t know exactly what his highest destiny was. Return trips to Colombia helped. In despair, he even applied to law school. Finally, it was something deep inside him that kept him going.

“The thing that saved me, in retrospect, was not an inner compass or any guiding light,” he says. “But for some quirky reason I was simply physically, psychologically, spiritually incapable of compromise.”

That involved repudiating the nine-to-five working life of his father, who commuted to work in flannel trousers, a jacket and tie. His father referred to the job as “the grind,” and, as a child, Davis thought his father meant he came home each evening a little bit shorter.

“I think in a way he did,” Davis tells me in an email.

Davis combined this abhorrence of banality with an unshakable faith in serendipity; in return, serendipity made him a favourite child. The year he was 33, for example, he finished his PhD, left Harvard, published his first book, made his first real money by selling the book rights to a Hollywood studio, ended a five-year relationship with a French woman, moved back to Canada, connected with his future wife, bought a house in Vancouver and conceived a child.

“You can’t calculate your way through life,” he says.

It has led to all the modern spoils of the storied explorer, including long and lucrative ties with the National Geographic Society, honorary doctorates, famous patrons, awards, fabulous prizes, more than a dozen books and a television series. He is one of just 20 living honorary members of the fabled New York-based Explorers Club, a select clan that has, over time, included Sir Edmund Hillary, the first conqueror of Mount Everest; astronauts John Glenn, Sally Ride and Buzz Aldrin; and Theodore Roosevelt, America’s 26th president.

He calls himself an “entrepreneur of knowledge” and avers he never held a formal job until his recent half-time appointment as a tenured professor of anthropology at the University of British Columbia, where he holds the B.C. Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk. Even that, though, offers plenty of time for off-campus adventure. He only teaches in the fall semester, and part of the deal is that he is excused from all the dull stuff, including meetings and administrative duties.

Everest at the head of the Kama Valley, one of the beyuls, or hidden lands, of

Guru Rinpoche, patron saint of Tibet.” Photo: Chris Chapman

Through all of that, Colombia has held a special place in his heart. He speaks of the nation as some men would speak of a lover, calling it a “visceral, even sensual” love.

“To be away for too long is to be on life support,” he writes in the book. “To step again onto the soil of the nation is to feel instantly that very sense of belonging that so long ago gave me the freedom to envision the man I’ve become.”

And Colombia loves him back. Ever since the 2002 Spanish translation of his book One River, about the Amazon journeys of his mentor, Harvard’s legendary ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes, Davis has been a hero in Colombia. In 2018, then-president Juan Manuel Santos gave him honorary citizenship.

So when the unexpected opportunity arose a few years ago to go back to Colombia to write a 7,000-word essay for a coffee-table book, he leaped at it. He’d been away for nearly two decades, following other passions. Bit by bit, Colombia took hold of him again. The result is Magdalena.

Over the past several years, in the run-up to the book’s publication, he has given a raft of keynote speeches in Colombia, including one at which 5,000 showed up to a 400-seat venue. His gift to Colombians, for so long used to seeing themselves as international pariahs, is that he can see the positives of the nation, says Xandra Uribe, the Colombian researcher and fixer who worked on the book with him for five years. After his talks, Colombians come up to him with tears in their eyes, asking, “How can we love ourselves the way you love us?”

“He’s bigger than this book. He’s bigger than life,” Uribe says. “He’s like a cult. People come and watch him speak again and again. They follow him.”

Will Magdalena finally be enough to fulfill Davis’s destiny? I wonder if he has more rivers to ford, more secrets to pry loose, more empathy to invoke.

In a speech delivered in 2019 at ZoomerMedia founder Moses Znaimer’s ideacity in Toronto shortly after he turned 65, Davis offered some hints. The video shows him striding across the stage like a lion, his rakish, wavy hair turning white. He likes the idea of ceding the field to a new generation, he tells the audience. He recounts the tale of Lew Welch, the American Beat poet who vanished into the woods of Nevada County in California in 1971 at the age of 44, never to be seen again. It sounds like a template.

He tells me he enjoys being old. There’s a glory to it. He has realized his dreams. One of his great joys now is to pass on his learning to the next generation, becoming an “oasis of safety” for young scholars in a frenzy to figure out what their lives are about. It’s why he insists on teaching a first-year class at UBC.

And yet.

When I talk with Uribe in Medellín, still his close collaborator, she lists several projects they are musing about, including maybe an IMAX film of the book. She hoots at the idea that he will fade into the woodwork.

“He is a force of nature,” she says, adding, “More than anything he wants to connect with people and inspire people.”

And he gives the impression of remaining firmly at centre stage. As we chat, he mentions that former Colombian president Santos, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, has just called to chat. A week after our interview, he forwards me an essay he wrote for Rolling Stone magazine, a searing indictment of the United States in the age of COVID-19 and President Donald Trump. The time of America, he wrote, is over.

It went viral. In its first hours online, he and the magazine’s iconic co-founder Jann Wenner already had kudos from actor Michael Douglas, musician Jackson Browne and industrialist Charles Bronfman.

If Davis were looking to be among men whose influence has held fast in their elder years, he could do worse.

He’s of the moment. Even the buzzy Twitter account Room Rater, which reviews the Skype and Zoom backgrounds of U.S. and Canadian pundits and politicos, weighed in. It gave Davis a nine out of 10 after he appeared on the PBS news show Amanpour & Co. to discuss his Rolling Stone essay. “Perfectly lit. Well angled. Great academic’s bookcase,” it tweeted.

But to Davis, the biggest upside to all this attention is that he can spread the word about Magdalena, he tells me. The essay has led to rounds of interviews on major American media, including CNN and PBS. Davis is in his element.

Like the river, he is still on a quest. Is it for recognition? For love? For absolution? Maybe he is fated to make amends for having let his fierce gaze slip away from Magdalena when he was young before coming back to her now. It’s hard to know. The heart of a master storyteller wears many disguises. Perhaps the answer is that, no matter how much he has accomplished, he is fated to spend the rest of his life telling the world about the wonders he has known.

To Colombia, With Love: An Excerpt From Magdalena

Travellers often become enchanted with the first country that captures their hearts and gives them license to be free. For me, it was Colombia. The mountains and forests, rivers and wetlands, the mysterious páramos, and the beauty and power of every tropical glen and snow-crested equatorial peak opened a doorway to a wider world that I would spend my entire life coming to know. In ways impossible fully to explain, the country allowed me, even as a boy, to imagine and dream. Coming of age in Colombia in the early 1970s, living on the open road, sleeping where my hat fell, I was never afraid. The warmth of the people enveloped a young traveler like a protective cloak, tailor-made for wonder.

This strange affair, the love of a boy for a land and a people, began innocently enough in 1968 when my mother, a modest but determined Canadian woman, told me that Spanish was the language of the future. She worked all year as a secretary to earn enough money to allow me to join a small party of schoolboys that a language teacher proposed to take to Colombia. At a time when most Canadians and Americans had never experienced a commercial flight, the South American destination was terribly exotic, as indeed was the character of the man leading the adventure. The teacher was English by birth, dapper in appearance, with a scent of cologne that in those days gave him the fey veneer of a dandy, an impression betrayed by the scars on his face and a glass eye that marked a body blown apart in the war. A perfect foil to orthodoxy, Mr. Forrester was mischievous, slightly transgressive, and more than a little subversive, traits of character that made him a total inspiration to teenage boys on the loose.

At fourteen, I was the youngest of the group and the most fortunate, for unlike the others, who spent a sweltering season in the streets of Cali, I was billeted with a family in the mountains above the valley, at the edge of trails that reached west to the Pacific. It was a classic Colombian scene: children too numerous to keep track of, an indulgent father, a grandmother who muttered to herself on a porch overlooking flowers and fruit trees, an angelic sister who more than once carried her brother and me home half-drunk to a mother, kind beyond words, who stood by the garden gate, hands on hips, feigning anger as she tapped her foot on the stone steps. For eight weeks, I encountered the warmth and decency of a people charged with a strange intensity, a passion for life, and a quiet acceptance of the frailty of the human spirit. Several of the older Canadian students longed for home. I felt as if I had finally found it.

Six years later, in the early spring of 1974, I returned to Colombia with a one-way ticket, a small backpack of clothes and two books, George Lawrence’s Taxonomy of Vascular Plants and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. At the time I believed that bliss was an objective state that could be achieved simply by opening oneself unabashedly and completely to the world. Both figuratively and literally I drank from every stream, even from tire tracks in the road. Naturally I was constantly sick, but even that seemed part of the process, malaria and dysentery fevers growing through the night before breaking with the dawn. Every adventure led to another. Once on a day’s notice I set out to traverse the Darién Gap. After nearly a month on the trail, I became lost in the forest for a fortnight without food or shelter. When finally I found my way to safety, I stumbled off a small plane in Panama, drenched in vomit from my fellow passengers, with only the ragged clothes on my back and three dollars to my name. I had never felt so alive.

Excerpted from Magdalena: River of Dreams by Wade Davis. Copyright © 2020 by Wade Davis. Published by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved

A version of this article appeared in the Nov/Dec 2020 issue with the headline “River of Redemption,” p. 34.

RELATED:

Jane Goodall: The Conservation Activist Is Still Making a Difference in Her 80s