‘The Father’ and Other Oscar-Pedigree Films That Capture the Reality of Dementia

With 'The Father' nominated for six Academy Awards, we take a look at other Oscar-pedigree films that capture the stark reality of dementia. Photo: Sony Pictures Classics/Courtesy Everett Collection/CP Images

To say Olivia Colman’s new film is about dementia sells it short. The Father is not just about memory loss but loss of self — a graphic reminder of our mortality. I remember visiting my father after his final stroke significantly reduced his mental functioning. My mother couldn’t bear to see him that way. But I loved how he would gaze out the window at the rustling leaves, happily lost in the moment, when he wasn’t compulsively checking his watch — two things Anthony Hopkins does in The Father.

Whatever the medical cause, dementia is not a disease like the others. It’s a vacant room where reality is sent spinning, which may be why actors and filmmakers are drawn to it. What happens to the mind when it loses its place allows a drama to go to extremes, into a zone where poetry is possible. Here are three Oscar-pedigree films that do that.

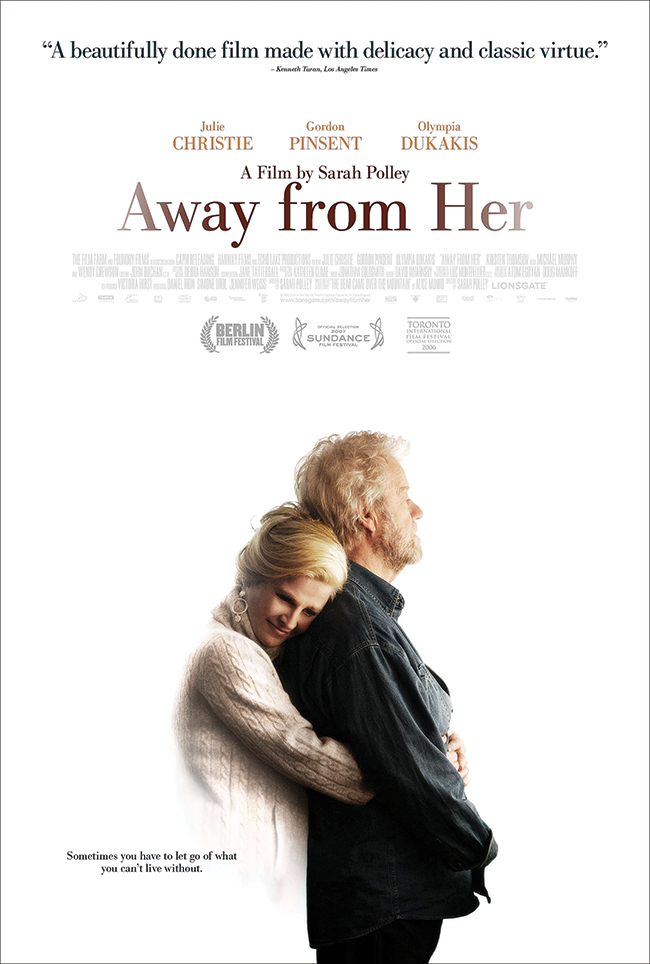

Away From Her (2006)

Florian Zeller, 41, who directed an 82-year-old Hopkins in The Father, is not the only writer-director to make a first feature with an actor at least twice his age playing someone with dementia. Canada’s Sarah Polley was 27 when she directed a then 66-year-old Julie Christie as Fiona, a woman afflicted by Alzheimer’s in Away From Her, adapted from a short story by Alice Munro. As Fiona’s mind unravels, so does her marriage. After she enters a nursing home, her husband (Gordon Pinsent) is soon erased from her memory. While treating him as a stranger, Fiona falls into a romance with a fragile fellow patient (Michael Murphy). But hints of her husband’s past infidelities suggest that at least some of her memory loss may be selective. Building emotion from small moments, the drama glides over the couple’s back story with no need to crack open its secrets. We can sense their presence. Polley’s script and Christie’s acting both received Oscar nominations, but we follow the story through Pinsent’s softly haunted eyes. His note-perfect performance is the film’s real treasure.

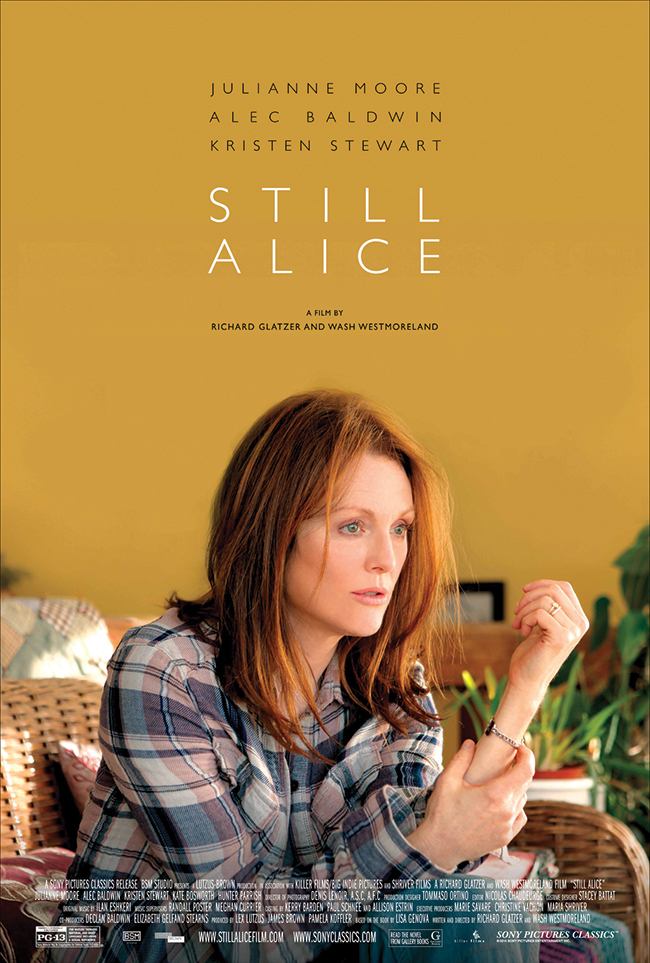

Still Alice (2014)

Dementia dramas tend to dwell on the emotions of the immediate witness, a spouse or family member. Still Alice is an exception. Julianne Moore won the Oscar for her tour de force as Alice, a linguistics professor and mother of three who conducts a losing battle against a rare form of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. As her keen intellect tries to keep pace with her mental decline, Alice leaves herself notes and even plots suicide with an instructional video addressed to her future self. The casting of Alec Baldwin as her husband is our first clue that he won’t be her most sensitive supporter. This actually is a movie about a disease on a granular level, one that follows a conventional arc, complete with an inspirational speech by Moore. She’s the reason to see it. Her performance overwhelms her co-stars – except Kristen Stewart, cast as her teenage daughter, an aspiring actress. With a script assist from Tony Kushner’s play, Angels in America, about souls rising from death “like

skydivers in reverse,” Stewart meets her elder head-on and sends Still Alice into the poetic stratosphere.

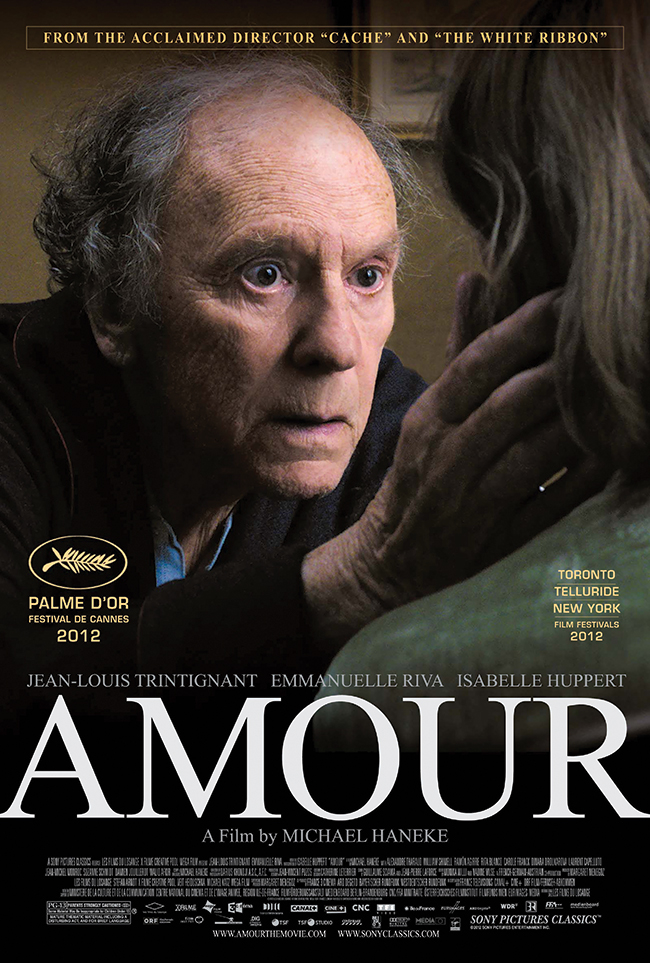

Amour (2012)

This intimate masterpiece picked up the Palme d’Or in Cannes, four Oscar nominations and a Best Actress win for the beloved Emmanuelle

Riva, who died five years later at 89. For director Michael Heneke, who is known for austere drama and clinical violence, Amour is unusually sweet but no less ruthless. He begins with a flash forward to the ending, as firemen break into an apartment to find the corpse of Riva’s character in a locked room, supine on a bed surrounded by flowers. The story follows her relentless decline from several strokes, as her devoted husband (Jean-Louis Trintignant) struggles to care for her. Set in a grand Parisian apartment full of old paintings and books, this is a palliative romance of agonizing beauty, difficult to watch yet impossible to turn away from. There are several interventions by the couple’s brusque daughter (Isabelle Huppert), who’s itching to dispatch her mother to a hospital against her wishes. “What happens now?” she asks her father. His answer: “It will steadily go downhill for a while, then it will be over.” We’re with him every step of the way.

A version of this article appeared in the Feb/March 2021 issue with the headline “Remembering Dementia,” p. 46.

RELATED: