We’re 36 minutes into what was supposed to be a 30-minute Zoom interview but, based on Stone’s — let’s call it reluctance — to let go of a badly phrased question, we are in no way ready to wrap this up.

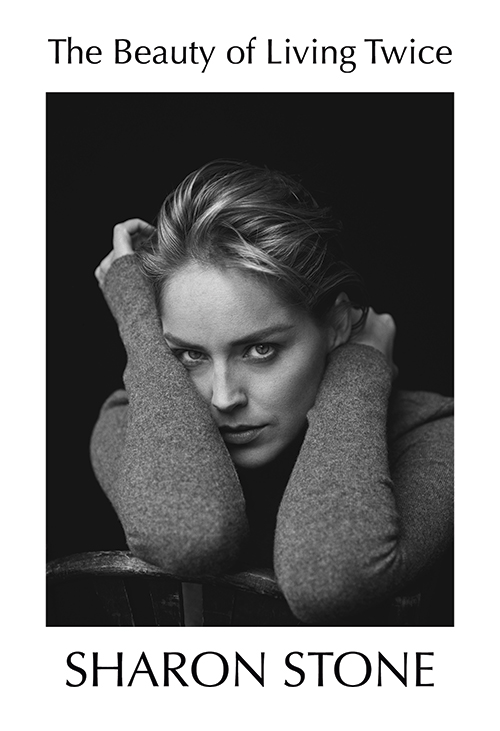

We’re talking about her new memoir, The Beauty of Living Twice, which dropped March 30. In late September 2001, Stone suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage, a dramatic form of stroke, and an artery connecting her brain and body pretty much shredded. She underwent a lengthy, risky surgery called endovascular coiling to repair the artery with metal coils. She recovered, but it took seven years, and — this is a key point of the book — she’s not exactly who she was before. The stroke was a hinge event: her life rearranged itself around it, bisected into Before and After. She writes eloquently of both.

“I wanted to do something not just good for my publisher and readers but good for me,” Stone says about writing her book, which took about two years. “I wanted to tell the truth.” Pause. “Within a few parameters.”

She’s sitting in a loveseat with a fluffy, furry throw in a dove-gray room in her West Hollywood home that once belonged to Montgomery Clift. There’s a large rectangular mirror in a gold frame, a vase of pink roses and, off camera, a dog named Bandit; she speaks to him now and then. She’s wearing a black-and-white plaid dress — I catch a glimpse of bare knee when she tucks up a leg — and two pendant necklaces, and she’s sucking on a lemon lozenge. Her voice is reedier than her screen-siren purr, and her frame is slighter. At one point, she stands and wraps her hands around her waist, to show me what “a tiny little person” she’s become, when she used to be, as she puts it, “ba-boom-ba.” Her blond hair is cut in a chin-length bob, and she rakes her hands through it as she talks, moving it from a shallow part on one side, to a deep part on the other, to pulled back without a part. Whichever way, it looks perfect.

“I wanted to do a real search about my life,” Stone continues. “How did I get in that position” — here she heaves a deep sigh — “slabbed out on a table in a hospital?” For some shaky moments in surgery, she was legally dead, “and I think we can all agree,” she says, “that’s the hitting-bottom moment in someone’s life. When you’re dead.” I can tell she likes that line; she allows herself a little smile. Sure enough, she repeats it. “We can agree dead is bottom.”

In addition to spending a decade as Hollywood’s reigning goddess, Stone, now 63, has written short stories and song lyrics. “I’ve had three No. 1 hits around the world,” she tells me — not boasting, just stating. “One here, one in Germany, one in Argentina.” In her memoir, she packs images, memories and insights into some sentences yet also knows when to go colloquial, when to throw in a tough-gal wisecrack. She explains some things thoroughly; others she only hints at. That’s a tantalizing combination, candour and mystique — a movie-star combination.

Her lean upbringing in rural western Pennsylvania comes vividly to life as does a family habit of leaving things unsaid (though she and her mother eventually discuss a huge thing they never admitted before, which we’ll get to). She acknowledges that her beauty made her a rarity — I appreciate that; so many actresses pretend they aren’t beautiful — and that her brain made her restless: A gifted student, she was skipped to Grade 2 when she was only five. She gives us delicious tastes of what her life was like. For example, one young man wooed her by driving into a lake, stopping just before the water sloshed in, and they sat with the radio on and the car lights dancing on the surface.

In her film debut, she played a vision, kissing a train window in Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories (1980). She kicked the crap out of Arnold Schwarzenegger in Total Recall (1990), directed by Paul Verhoeven, and then posed for Playboy to convince Verhoeven to hire her for his next project. That film, Basic Instinct (1992), hit like a thunderclap. I was living in L.A. then and I cannot oversell you on how huge that movie was. It was on every billboard, fodder for every late-night talk show. Feminist groups, angry at its depiction of Evil Bisexuals, stalked the blocks-long ticket lines handing out flyers with the spoiler, “Catherine did it.” (Catherine is Stone’s character, a diabolical novelist.)

I watched Basic Instinct recently and, god, it’s misogynistic — and not only for the infamous no-underwear-uncross-legs scene. Catherine’s sexuality is never hers; it’s only about how it titillates and threatens men. Hollywood in the 1990s was obsessed with vertical integration, conglomerates buying up studios to create product for their pipelines. The commodification of female bodies was part of that, and Stone’s body was commodified the most.

Her nine-day brain hemorrhage ended that, too. She rattles off how it impacted her. She lost her long- and short-term memory, directional hearing in her right ear and the ability to read and write for three years. One foot dragged. The right side of her face fell. “The Dalai Lama told me I reincarnated into my own body,” says Stone, a Buddhist who was introduced to the Tibetan spiritual leader by Richard Gere. “So to go back, to be back, emotionally, in that other person, is not something I even want to do. People want and expect her, and that just isn’t working with me.” She still has glamorous “Sharon Stone clothes” in one part of her closet and more casual “me clothes” in another part. (Though those modes sometimes meet in the middle: Stone famously wore Gap to the Oscars twice — a black T-shirt in 1996 and her then-husband’s white shirt in 1998 — becoming an icon of American fashion insouciance.)

But then, as if I’d teased something awake in her, Stone enters her second galactic wormhole of our conversation. (We fell into the first one right off the top, when she spent six minutes assuring me that she wrote her own book. I never imagined otherwise.) This one lasts from minute 21 to minute 31, and it is epic. At the peak of Stone’s fame, she says, fans tore clothes off her body; they’d grab her breasts and buttocks. “I told the studio, ‘You will bring me Mossad bodyguards. Because we can’t keep calling SWAT.” She acts out the gesture the Mossad guards would use — hands out, elbows bent, like carrying a tray — when they wanted permission to touch her, explaining, “Israeli men treat women as peers.” The guards would literally carry her out of danger, “and they would have to be six feet tall because I’m six foot in heels.” She describes how crowds would surround her limo and rip off the mirrors, bumpers, licence plates and wipers; then they’d climb on the roof, and she’d crouch down as it caved in, “thinking, ‘I’m going to die in here.’” She’d finally get inside whatever venue and “I’d be like, [panting], and they’d safety-pin my dress together, wipe the sweat from my face and push me into the spotlight.”

She recalls hosting Saturday Night Live, when haters rushed the stage, Lorne Michaels called for security, guards were escorting them out and the stage manager was counting her down, “LIVE in five, four, three …” She tells me about being on stage at the MTV awards with Michael Moore, “and we were covered in hundreds of laser sights because we were advocating gun control,” she says. “I said, ‘We’re in it now, motherf****,’ but we stayed on.” When they finished, bodyguards hustled them to armoured cars, which they’d driven “into the building and onto the stage.” She remembers a car following hers from the airport, repeatedly rear-ending her; a helicopter landed in her L.A. backyard, “and the windows are vibrating, and a guy hanging out the belly in a harness is holding this huge cylinder — it looks like a gun — and I’m in my underwear, crawling up my wooden stairs, terrified, my knees are bloody, and then I realize he’s holding a camera.” She is bouncing on the sofa during this story.

“This is the way my life went for 10 years,” Stone says, “day after day after day after day of this kind of insanity. So no, I don’t want to go back and get in that part of my life, and ask, ‘How did you feel?’ Because how could I have felt? I felt like a person under siege.”

I attempt to ease Stone’s agitation by lobbing what I think is a softball reference to a story in her book about working with Meryl Streep, deep in their careers, on Steven Soderbergh’s film The Laundromat (2019). But oh-ho-ho, I am so wrong, and we instantly plunge into a third wormhole, the deepest one yet. So before I get into that I will back up, to a moment of healing brought about by her memoir.

In the book, Stone describes how her maternal grandfather sexually abused her, but she and her sister, Kelly, never talked about it until Stone began writing about it. That brought the sisters closer. Kelly then had a heart-to-heart with their mother, Dorothy, and told her about the assaults; Dorothy wrote Sharon a long letter and then came for a visit (hitherto, a rare occurrence) about a year into her writing process. “I didn’t know my mom. I didn’t have a relationship with her,” Stone says. “I didn’t understand her, I didn’t understand her life. I didn’t understand how she treated me. I thought she was a horrible person.”

Stone read Dorothy what she thought was a final draft of her book. Then Dorothy talked for an hour and a half straight, and Stone recorded her. Then Stone rewrote the book. “Dorothy told me her father beat her mother every day until the day she died,” Stone says. “I know she’d never said it out loud before.” Dorothy also told her daughter, “Now I see why you couldn’t look at me.” That stabbed Stone in the heart.

The honesty broke down the wall between them. “We suddenly were not just mother and daughter,” Stone says. “We were two adult women, sharing this experience. I’m extremely grateful that my life is changing in this way. When you gain a mother” — she laughs — “you can’t really feel like you lost a lot. Not very many people suddenly get a mother, especially their own mother, when they’re 60.”

In fact, Stone is welcoming more and more women into her life. “I’m really glad I know now that women are my friends, that my female colleagues are my friends,” she says. “I know it’s women who are here to heal us, and guide us. I know that we are moving into a female future. I want to work with women. I’ve spent my whole life working with men. That made the masculine side of me maybe over-strong.”

Which brings me to my ill-fated question.

In her memoir, Stone writes about how Hollywood — and society — pit women against each other. “It was put to us that there could be room for only one.”

“I find that fascinating,” I say. “So when you finally got to work with Meryl Streep, you realized –”

Stone stops me. “I like the way you phrase that, that I finally got to work with Meryl Streep,” she says. “You didn’t say, ‘Meryl finally got to work with Sharon Stone.’ Or we finally got to work together.”

“Good point,” I start to say – “Because that’s the way her life went, she got built up to be, ‘Everyone wants to work with Meryl,’” Stone says. “I wonder if she likes that?”

“You’re right,” I start to say – “The way you structured the question is very much the answer to the question,” Stone says. “The business was set up that we should all envy and admire Meryl because only Meryl got to be the good one. And everyone should compete against Meryl. I think Meryl is an amazingly wonderful woman and actress. But in my opinion, quite frankly, there are other actresses equally as talented as Meryl Streep. The whole Meryl Streep iconography is part of what Hollywood does to women.”

“I hear you,” I start to say, but Stone is on a roll. She starts listing names. “Viola Davis is every bit the actress Meryl Streep is. Emma Thompson. Judy Davis. Olivia Colman. Kate Winslet, for f***’s sake. But you say Meryl and everybody falls on the floor.”

“I actually agree with you,” I start to say – “I’m a much better villain than Meryl,” Stone goes on, “and I’m sure she’d say so. Meryl was not gonna be good in Basic Instinct or in Casino,” for which Stone earned an Oscar nomination. “I would be better. And I know it. And she knows it. But we’re all set up to think that only Meryl …” – here Stone’s voice goes all breathy, and she stretches out her arms in an arabesque, left arm forward – “is so amazing …” – right arm forward – “that when you say her name …” – left arm forward – “it must have been amazing …” – right arm – “for me to work …” – left arm – “with her.”

“I’m so sorry,” I start to say – “That’s how you’re set up to ask the question. That’s how we’re set up to think,” Stone says. Breathy voice again: “Because I could never … touch the heights … We’re all labelled the Queen of Something. I’m the Queen of Smut! She’s the Queen of That! We all have to sit in our assigned seats. Are you kidding me? If we worked in a supermarket, she can’t always be the No. 1 checkout girl. We’re all doing our jobs. Everybody gets to get better, and everybody gets to sometimes have that not great a day. Even … Meryl.”

“Absolutely,” I start to say – “That phrasing has been taught,” Stone says. “We’ve been taught that everybody doesn’t get a seat at the table. Once one is chosen, nobody else can get in there.”

That seems to end the storm. The set-up that Stone is objecting to — that one woman or one person of colour is “enough,” and everyone else has to vie for scraps or settle for being less-than — is rife in every profession, and it’s demeaning, unfair and incorrect. But I feel she’s made the point — thoroughly! — and we should move on. How does Stone feel about #MeToo? “It can’t

just have been this blip in Hollywood, where one guy [producer Harvey Weinstein] went to jail,” she replies. “Harassment is everywhere. Until there are real laws, #MeToo was just the opening sentence. I’m sure Meryl has a story. But I’m also sure if Meryl told you her story, she wouldn’t be being Meryl, and she wouldn’t be getting those jobs. Meryl can’t be the envelope pusher. Because then she wouldn’t get the jobs. Meryl’s a smoother. That’s what she does.”

Again, Stone isn’t wrong; Streep has been criticized for her silence around #MeToo. But the clock is ticking, and I still have a stack of questions.

“I don’t have an agent or manager or lawyer,” she says. “If a director wants me, they’ll find me. If you want to hire me, you have to want me. At 63, you’ve seen what I can do. I don’t want to be on a list or a name to help finance a project. I want to work because I’m the best person for a job.” In her most recent projects, which include the limited series Mosaic, a guest appearance on Better Things and a mischievous role in Martin Scorsese’s pseudo-documentary Rolling Thunder Review, she is as singular and hypnotic as ever. Due out soon are a romance co-starring Andy Garcia and a drama written by Lena Waithe.

Stone’s long-term publicist, Cindi Berger, chooses this calm moment to give me the “last question” warning. “What are you glad you know now? What are you sure of?” I ask.

“I love being a mom,” Stone says immediately. She has three sons, Roan, 20, Laird, 15, and Quinn, 14. “I’m really grateful to have caught up with myself. I know that we have to be in the day that we’re in. If COVID has taught us nothing except that we should be present, then we’re learning something. I know I will live authentically. I’m hoping this effort I made will encourage others to live authentically.”

Stone seems open, so I sneak in one more: “What would you say to your younger self?”

“I went to university when I was 15,” Stone replies. “I would say to her, ‘I know this is all terrifying, and you don’t feel ready. And nobody is helping you.” Another shaky sigh. “But don’t ever, ever doubt your instincts. When you doubt your instincts, you’re going to get hurt. Any mistake you make following your instincts will be okay.

“And I would keep saying that to myself every step of the way,” she continues. “Every mistake I made came from trying to think ‘logically’ — I should be doing this or that. And for everything I did right, I thought, ‘This is really gonna be hard, and everybody is gonna think I’m crazy, I feel sick, I have no idea what’s going to happen, and it all looks, ugh. But I know it’s what I’m supposed to do.’ And that’s the thing that turns out okay.”

I know a good final line when I hear one. I open my mouth to thank her. But Stone keeps going. “I’m doing that now by writing this book, by not having any representation, by telling these horrible truths,” she concludes. And then, at minute 52, she can’t help herself. “And even by saying that — though Meryl Streep is fabulous — the idea that she’s the queen, and only she, has gotten absurd. I know that sounds sacrilegious. But it’s enough already.”

So close to a clean getaway! But Sharon Stone is Sharon Stone, somewhat broken but unbowed. She wouldn’t want it any other way.

A version of this article appeared in the April/May 2021 issue with the headline “54 Minutes With Sharon Stone,” p. 37.

RELATED:

Hollywood’s Ongoing Problem With Aging Down Female Characters

Dame Helen Mirren Talks Her HBO Series “Catherine the Great”