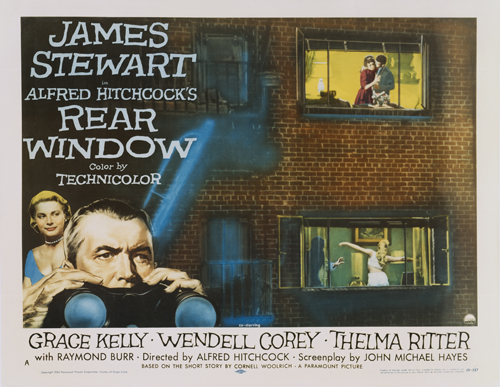

“Rear Window” Turns 67: Revisiting the Quintessential Hitchcock Summer Film

Photo: Paramount Pictures/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Part suspenseful domestic thriller, part love story, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window is a masterpiece. Just as psychological thrillers are perfect reads for these balmy days, now is the perfect time to watch this iconic film, because it’s also a quintessential summer movie.

Set during a heat wave, Hitchcock ratchets up the tension during the inertia of oppressive humidity and it becomes a pressure cooker. The only one who doesn’t break a sweat? Star Grace Kelly, soignée in a wardrobe of crisp suits and airy dresses. Having broken his leg on assignment, her photojournalist boyfriend L.B. Jeffries (James Stewart) is confined to a wheelchair overlooking his apartment courtyard. As the barometer rises, he has nothing to do but watch the comings and goings—and speculate on the lives of his neighbours. And as Hitchcock raises questions about the ethics of surveillance, he involves the audience in the act of voyeurism.

Rear Window premiered in early August 1954. To mark its 67th birthday, we examine the elements that make it a masterpiece.

Its Biggest Star is Silent

The most important element in Rear Window is not either of its major stars. It is the set. Inspired by a real New York location, the classic single-set film’s Greenwich Village courtyard and surrounding buildings (some six stories high) were on a massive scale. Marketed as the work of fifty to build, it was the largest single set in Paramount’s history with 31 scale size apartments, 12 of which were fully furnished, it occupied an entire sound stage and cost a reported quarter of the film’s budget (unprecedented at the time) to build, including functional drainage for the rain scenes. And to achieve the choreographed precision of the subjective camera and a complete control of lighting patterns, the movie features the prowess of frequent Hitch collaborator like cinematographer Robert Burks, a veteran of twelve Hitchcock films.

It Anticipates the Future (Including Instagram)

Rear Window’s original marketing touted Jeff’s peeping as, “revealing the privacy of a dozen lives.” It is like the entertainment of individual screens. “He was looking into the future and imagining a world of mediated images,” Canadian production designer Rocco Matteo (The Kennedys, Condor) once explained to me. He points out that the neighbours’ windows are also all along the back, so metaphorically we’re not seeing the front face they present to the world but the real glimpse into their lives: Truth is a rear window. “The next decade you have Blow-Up starting to examine the same idea, as a cultural malaise, of a photographer who could only connect to people through images.” Today, the window squares framing each random, unrelated life could be an Instagram post.

There’s Subtext

Instead of dealing with the crossroads in his personal life, Jeff focuses on what is going on outside. He’s reluctant to give up his freedom and commit to his girlfriend and the various apartments play out his options as though each window’s narrative were a possible future outcome: the diminishing affections of a once-passionate newlywed couple, social butterfly Miss Torso, Miss Lonelyhearts and her disappointing dates, the stoic solitary songwriter, and an unhappy marriage he suspects has ended in murder.

One of the Characters is Also An Inside Joke

Based on the 1942 Cornell Woolrich Dime Detective magazine story “It Had to Be Murder,” there are major differences and additions. Hitchcock and screenwriter John Michael Hayes give Jeff a specific career, change his sole companion into a no-nonsense wisecracking caretaker Stella (the great Thelma Ritter), and add dimension by writing in a girlfriend, with Grace Kelly (fresh from his Dial M for Murder) in mind for the part. One infamous inside joke is that the suspected villain Thorwald (Raymond Burr) is intentionally styled to resemble Hitchcock’s nemesis, former producer David O. Selznick.

It’s Designed for the Big Screen

You can’t get this on the small screen. Television was on rise in 1950s and encroaching on Hollywood supremacy with cheaper, more convenient access to entertainment than going to the movies. Rear Window’s level of cinematic spectacle, filmed in Technicolor and projected in a new widescreen format usually reserved for big-budget biblical stories, historical dramas, and westerns, was by design. It was a salvo in the ongoing war against television. The only reason that Jeff is watching the goings-on in his courtyard in the first place is that he doesn’t own a TV.

The Fashion is Iconic

And we don’t mean Jeff’s pajamas. Hitchcock brought in the legendary costume designer Edith Head, winner of eight Academy Awards, to create the costumes for actress Grace Kelly. These have since been exhibited in the Victoria & Albert retrospective on Kelly’s style, and even the sketches sold for five figures at Christie’s auction.

Kelly’s lavish wardrobe is on one level to entertain the audience like a fashion show, to be sure. (And no spoilers, but her character’s style knowledge and bravery also solve the film’s central mystery.) Since her character was New York society girl Lisa Fremont, Head could justify modelling a wardrobe on the very latest looks from Paris and took inspiration from designers like Cristobal Balenciaga (for the green luncheon suit) and Christian Dior (the full tulle skirt). But her stylish outfits are also a secret weapon in the storytelling…

Even the Smallest Details Have Meaning

According to biographer Jay Jorgensen, Hitchcock told Head he wanted Kelly to resemble an untouchable piece of fine Dresden china. “There was a reason for every color, every style, and he was absolutely certain about everything he settled on.” It’s glamorous but with simple colours and few patterns, except to add meaning in pivotal scenes. When Lisa bravely crosses the courtyard to Thorwald’s apartment, for instance, she’s in a delicate floral dress that emphasizes her femininity and vulnerability.

Set and costume conspire together to drive home romantic conflict and the confirmed bachelor’s reluctance to get serious, like when Lisa sails into his apartment wearing an exaggerated gown that overtakes the cramped space. In the scene where she flits about his apartment turning on lamps, the frothy skirt brushes up against objects and catches on the furniture. You think you’re looking at fashion but it’s contributing to the director’s and thematic intentions, emphasizing the character’s psychological experience of how Lisa takes up both physical and emotional room. Production designer Matteo also points out is how in the apartment, there’s a step up to get out the door – and because Jeff is confined to a wheelchair that means he’s physically trapped and can no more escape the villain than he can his girlfriend.

It’s Inspired by a True Hollywood Love Story

The movie’s other biographical allusion is secondhand. Critic Steve Cohen has suggested that making Jeff a photojournalist borrows from the rumoured romance Hitchcock witnessed between Ingrid Bergman and Robert Capa, the famed Hungarian-born war photographer and co-founder of Magnum Photo. After meeting Bergman in Paris he followed her to Hollywood where she was starring in Hitchcock’s Notorious (he snapped many of the on-set stills and photo essays of her for Life). As the camera pans the apartment, notice the set decoration clutter: the smashed camera, the stacks of Life magazine, even the nature of the framed snapshots. The explosions, military scenes, and car wrecks could be mistaken for a portfolio by the man who once pronounced, “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Bergman was smitten but Capa was ambivalent and eventually broke it off and went back out into the field. “So that’s it,” Lisa says to Jeff when they quarrel. “You won’t stay here and I can’t go with you.”

It’s As Honored as it is Satirized

Even if you’re Hitchcock, you haven’t truly made it in pop culture until Looney Toons or The Simpsons give you a cartoon parody nod. (That came in 1994 with “Bart of Darkness,” when Bart breaks his leg and suspects Flanders of killing his wife.) Rear Window’s influence, from photo shoots in Vogue and the commentary on surveillance of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation to the staged murder of a woman across the canyon in Brian De Palma’s Body Double and Woody Allen’s homage caper Manhattan Murder Mystery — there’s even a voyeur window scene in Friends.

Added to the Library of Congress National Film Registry in 2005, Rear Window is on the American Film Institute’s list of 100 Greatest American Films. For more analysis of the movie, scholar John Belton’s Rear Window anthology is a good place to start.

Culture writer and critic Nathalie Atkinson is the host of Designing the Movies, the monthly film series at Toronto’s historic Revue Cinema where art direction, costume and production design are the lens for analysis. In the past, she’s presented Rear Window with special guests like Hitchcock makeup artist Julie Hewett and production designer Rocco Matteo.

This story was originally published on Aug. 9, 2019.

RELATED: