‘Oscar Peterson: Black + White’ Doc: Exploring the Canadian Jazz Giant’s Monumental Life and Legacy

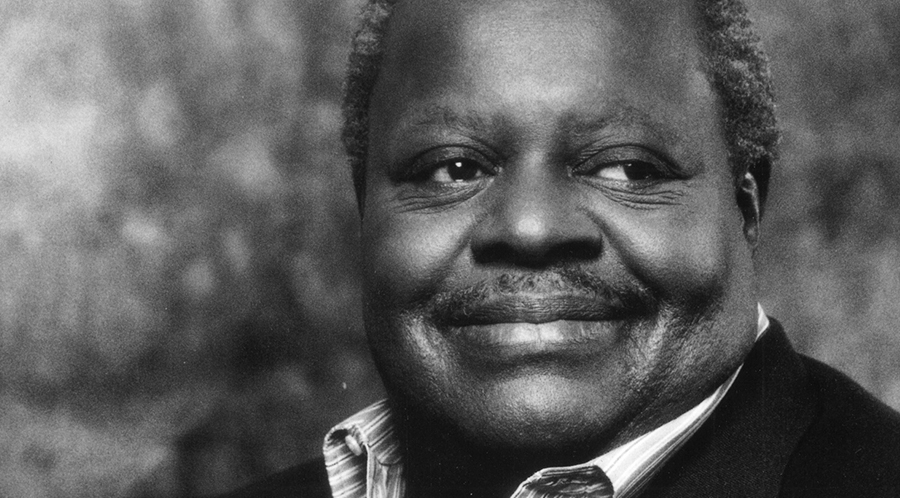

The life and legacy of Canadian jazz legend Oscar Peterson, seen here in an undated photo, is being celebrated in a new documentary that premiered at TIFF this week. Photo: Courtesy of TIFF

The Barry Avrich-directed documentary Oscar Peterson: Black + White made its world premiere at TIFF in September. And ahead of its premiere on Crave this week, we revisit Zoomer’s interview with Avrich and Peterson’s widow, Kelly, to discuss the jazz legend’s life, music and legacy.

“I don’t mean to brag about this, but it turned out bigger than I expected.”

Canadian jazz legend Oscar Peterson utters these words about his iconic Civil Rights anthem “Hymn to Freedom” in the new documentary Oscar Peterson: Black + White. But, in truth, the sentiment could be used to describe Peterson’s entire career.

Born in Montreal in 1925, a bout of tuberculosis as a child forced him to discard the trumpet and take up the piano. He studied classical piano formally but his passion lay in emulating jazz heroes like Nat King Cole, Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson. He left school at 17 and began playing and recording professionally, eventually catching the ear of legendary producer and manager Norman Granz, who booked him at Carnegie Hall. From there, he toured the world with the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie and other greats as part of the Jazz at the Philharmonic concert series before forming his first Oscar Peterson Trio — eventually becoming one of the most celebrated jazz musicians in history.

Directed by Canadian filmmaker Barry Avrich, 58 — whose past documentaries explored the fascinating lives of everyone from Hollywood producer Lew Wasserman (The Last Mogul, 2005 ) to the last living Nuremberg prosecutor (Prosecuting Evil: The Extraordinary World of Ben Ferencz, 2018) — the film chronicles Peterson’s incredible journey through archival interviews with the jazz great (who died in 2007 at age 82) as well as a roster of musical heavyweights and historians who speak to his genius and even play some of his tunes.

“Oscar Peterson revolutionized the piano … I didn’t know that a piano could be played that fast off the top of your head,” rocker Billy Joel attests in the doc. Grammy-winning jazz pianist Ramsey Lewis adds that Peterson, “is what Muhammad Ali meant to boxing, what Michael Jordan meant to basketball.”

“I was just driven by the pace of Oscar’s music,” Avrich — a fellow Montrealer — says of making the film. “It’s just the way he played. We moved at that pace and got this film done in seven months.”

The timing, meanwhile, is right for the doc, since Peterson is having a bit of a moment. In February, Historica Canada released a new Heritage Minute celebrating him while, in August, Peterson’s hometown of Montreal announced it would create a public square named after him.

With Oscar Peterson: Black + White making its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival this week — you can still catch a digital screening on Saturday, Sept. 18, or watch it when it premieres on Crave on Oct. 22 — Zoomer’s Mike Crisolago spoke with director Avrich and Peterson’s widow, Kelly, 65 (who also served as the film’s consulting producer) recently over Zoom about the jazz giant’s life, the romance between Oscar and Kelly and why now is the right time to celebrate his legacy.

Why is now the right time for a documentary about Oscar Peterson?

KELLY PETERSON: Well, I would say there’s never a wrong time to make a beautiful filmed portrait of Oscar. He’s deserving of the attention that he’s getting and the dedication and devotion that Barry and his team put into this — with all of the phenomenal research they did and all that they’ve uncovered — is just remarkable. So as far as timing, you can always find anniversaries to pin things on and there isn’t one. It’s just now. And what a good time.

Barry, you had a personal reason for wanting to take on the subject of Oscar Peterson.

BARRY AVRICH: Well, Mike, I’ve always felt I’ve been open about this, that we just don’t do enough to celebrate Canadians — especially their contributions globally — like Oscar. And so, in my filmography, I’m a big proponent of celebrating Canadians. That’s one. Two, last fall I really was feeling reflective. My mother, who’s going to be 93, and not in great shape, introduced me to six albums that she had in her house in Montreal growing up. And so Oscar was one of them and she would take me to Place des Arts to see Oscar. And as I’m in that act three with her right now, I just felt really reflective and said, “This is what I want my next project to be.”

Kelly, when is the first time you remember being exposed to Oscar’s work?

KP: When I first heard his music, it was as a child. My parents played Oscar’s music all the time in our house — Oscar and Duke [Ellington]. But I heard Oscar’s music growing up and then heard him in person for the first time in 1976 with my mother and my brother in Rochester, New York [just after graduating from university].

Kelly, you were working in a restaurant in Florida in 1981 when Oscar came in and you met him. You were 25 and he was 55. When you began dating shortly after that, what was it like for you to say to your family, “Meet my new boyfriend. It’s Oscar Peterson”?

KP: Actually, for quite some time during our courtship, I didn’t tell my family about how involved Oscar and I had become. My father had already passed away and my mother knew that I was traveling with Oscar. There was nothing hidden there. It was just the development of the romance that I kept very private. And as I reflect on that, I think really that’s because it was really magical and it was so surreal that I wanted to protect the sanctity of it. It wasn’t until less than a year before he asked me to move [to Toronto, in 1986] and live with him that I told them.

What did your family think of Oscar as far as a suitor for their daughter/sister?

KP: Really, they adored him and they loved him, my mother and my brother. My brother’s concern was more about our age difference and knowing that, because our father had died so young, at age 42, and our mother was alone, he said, “Kelly, I’m really worried about you with someone who’s 30 years older and what that might hold for your future.” Which was so precious and wonderful of my brother. And my response was “Well, yeah, but dad died at 42. We don’t have any guarantees. So I need to be with the man that I love rather than worrying about age.”

The film includes not only the highlights of Oscar’s life, but lowlights too — such as the struggles with racism he faced on the road.

BA: You could not leave out Oscar’s experiences on the road. We were all aware of the continuing divisiveness and tremendous prejudice around the world. And I wasn’t aware of the depth of [that in] the music industry until I saw the movie Green Book and read Oscar’s biography a few times. So you could imagine touring and going to venues with thousands of people, where there would be this pouring of adulation towards Oscar and his musicians. He’d come off of stage and people would say, you know, “Mr. Peterson, that music was unbelievable.” Oscar, being the man he was, would put his hand out and say, “Thank you, what a pleasure to meet you.” And they go, “Well, I’m not going to shake your hand.” And by the way, Oscar would want to use the bathroom and the theatre that he was playing at? “Nope, outhouse in the back.” [Or] “Sorry, you can’t stay at that hotel.” That disconnect for him must’ve been extraordinarily shattering, to come off a stage with such a high and then go to some D-standard motel and just say, “What am I doing this for?” … But I couldn’t leave that piece of storytelling out of the film. If Oscar were alive today, I think he’d be thrilled that “Hymn to Freedom” still resonates. What has changed today from when Oscar wrote that piece over 60 years ago? Nothing. So, that’s the message of that piece in the film and the message of that song — we must come together. Extraordinary.

Barry, if you had a chance to ask Oscar a question for this documentary, what would you still want to know?

BA: I think I would ask Oscar if he felt he had created the perfect composition — if he was satiated in his life, musically. I mean, so many actors — Olivier felt that he had never performed the ultimate role or performance. And Kelly can answer this — was Oscar truly at peace creatively?

KP: I think he was at peace creatively, but if you asked him if he felt that he had achieved all he wanted to achieve, he was always looking to improve. Every concert that he performed, he expected himself to play better than the previous one. He was always reaching for more excellence and going higher. But being at peace? Yeah. He felt so comfortable and had such joy in all of it that it was kind of being at peace.

The documentary shows Oscar later in life, suffering a stroke in his 60s and falling into a depression before pulling himself up and winding up back on stage a year later. So I’m wondering if there’s a lesson there for the rest of us in terms of encountering obstacles as we age.

KP: It’s a story of resilience. Especially the stroke —coming back from that … It’s resilience, it’s determination, it’s dedication. It’s not letting something external take away what you love to do. And Oscar, as long as I had known him, had always said, “If I can’t do what I expect of myself, I won’t walk out on the stage. But until then I’m not going to let anything else stand in my way.” It wasn’t only the stroke. He had systemic arthritis and there were times when he would come off stage at an intermission and his hands felt like ice cubes. But he still played what he played. So it’s that constant going and having expectations, having goals and curiosity with always wanting to know more about technology and constantly learning, constantly exploring new ideas. And I believe a great deal of that has to do with music. I think that Oscar is unique in his own talent but I think for everyone, if we have music, it keeps our brains more active.

What do you both hope viewers will take from this film in terms of Oscar’s legacy?

BA: Well, I think Oscar wrestled with acceptance in Canada … tall poppy syndrome on that end of it. And it’s great that he’s on Canada’s Walk of Fame and it’s great that he’s on a stamp and it’s great that they keep naming things after him as they should. I just want to make sure that if there’s a global Mount Rushmore of jazz giants, he’s there. So I think, with this documentary, if another hundred, another thousand, another a hundred thousand people say, “I want to listen to Oscar’s music again,” great. Let’s just keep that moving along.

KP: I would answer the same way. And what I anticipate [is] there are going to be a lot of jazz fans and a lot of Oscar fans who want to see this film because they always want more and they want to know more. But I also believe that there will be people who just like to see documentaries, or people who are interested in music documentaries, or people who just like to go to the movies and want to watch, who might not really know anything about Oscar, or might only know a little, and then they will discover more. They’ll hear the music and hopefully that will make them want to go and listen to more recordings and explore more of Oscar’s music and maybe even more of jazz.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.

Oscar Peterson: Black + White is available at TIFF via digital screening on Saturday, Sept. 18, and premieres on Crave in Canada on Oct. 22.

RELATED:

New Heritage Minute Featuring Canadian Jazz Legend Oscar Peterson Debuts for Black History Month