Unvarnished Truth: How Writing My Father’s Memoir Helped Me See Him in a New Light

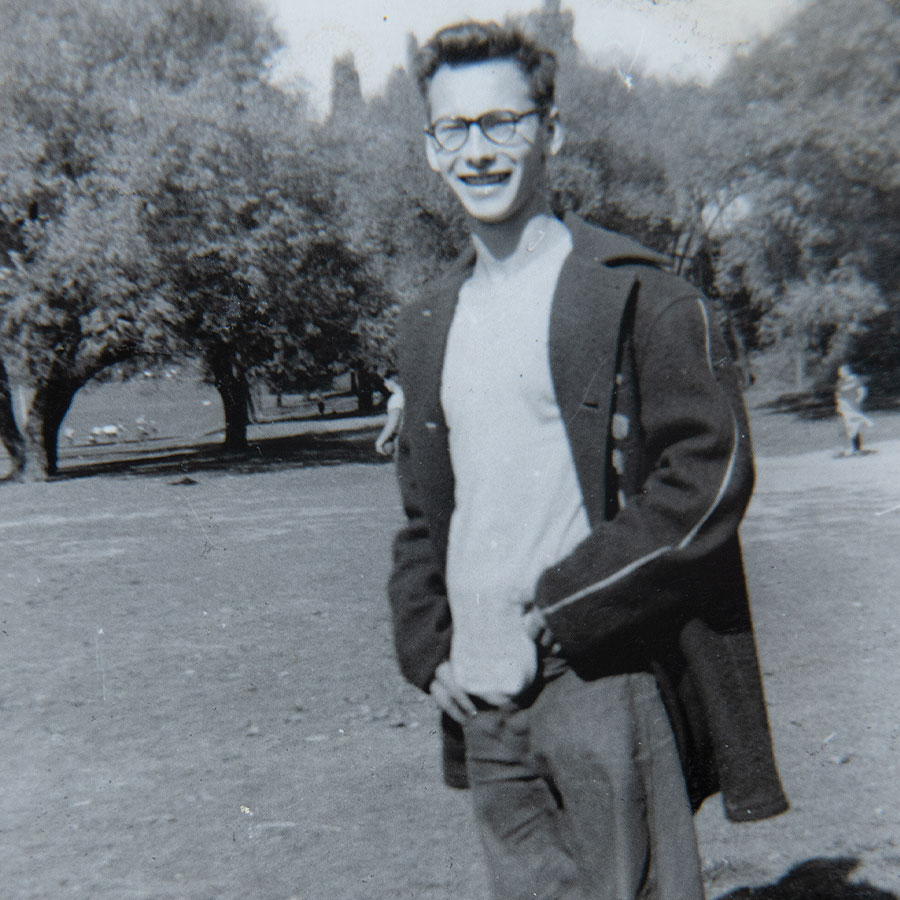

Writer Aviva Rubin says she's seen her father — pictured above at Bickford Park in Toronto in 1949 — in a new light since taking on his memoir. Photo: Courtesy of Aviva Rubin

As 2020 drew to a close and my father, Murray Rubin, was approaching his 90th birthday, he got an email from a U.S. company that ghostwrites memoirs. My parents live in a condo with nice light and space, but the pandemic was raging outside and life was lonely. Perhaps a book about him would help. He was about to express interest when my mother Roda suggested that I, the eldest of his three kids, and a writer who has been dragged into many of his schemes, might be a better option. Given Murray’s constant refrain at family gatherings — in front of his young grandchildren — that he doesn’t want any bullshit, nicey-nice eulogies when he dies, I was the perfect choice. Without overthinking decades of criticism and wrestling for control of my life, I jumped in. (No sugar coating, Dad, I promise.)

My father is very unconventional for a Jew born in Toronto in 1931 to Polish immigrants. His path, aside from sexual orientation, has never been a straight one. A pharmacist by training, he started a unique, mail-order, prescription business that prompted an Ontario Superior Court challenge and grew into a chain of drugstores called Vanguard; bought a blueberry farm; raised more than $150,000 to build a monument to fallen Second World War soldiers from his beloved Harbord Collegiate high school in Toronto; carved animals out of granite; ran for the federal Conservative nomination in the Toronto riding of Eglinton-Lawrence in 1980; instituted a 20-chews-per-mouthful rule to slow the lightning pace of our childhood dinners; and travelled, hiked or biked on every continent except Antarctica.

We start daily calls with me at home with my laptop and my iPhone on “record” and my parents together in their den. Unlike so many face-to-face visits that ended abruptly when he lost interest and left the room with no explanation, the book keeps him engaged.

The working title, Tomorrow Was Always Too Late For Me, comes from a history of Vanguard he penned, and captures a life spent hurrying to the next activity. On a trip to Costa Rica years ago to visit a friend’s guesthouse, he was impatient to get there, and irritated when we stopped for a beer in the magical jungle to wait for a flooded-out bridge to be fixed. “But Dad,” I said, “we are there.”

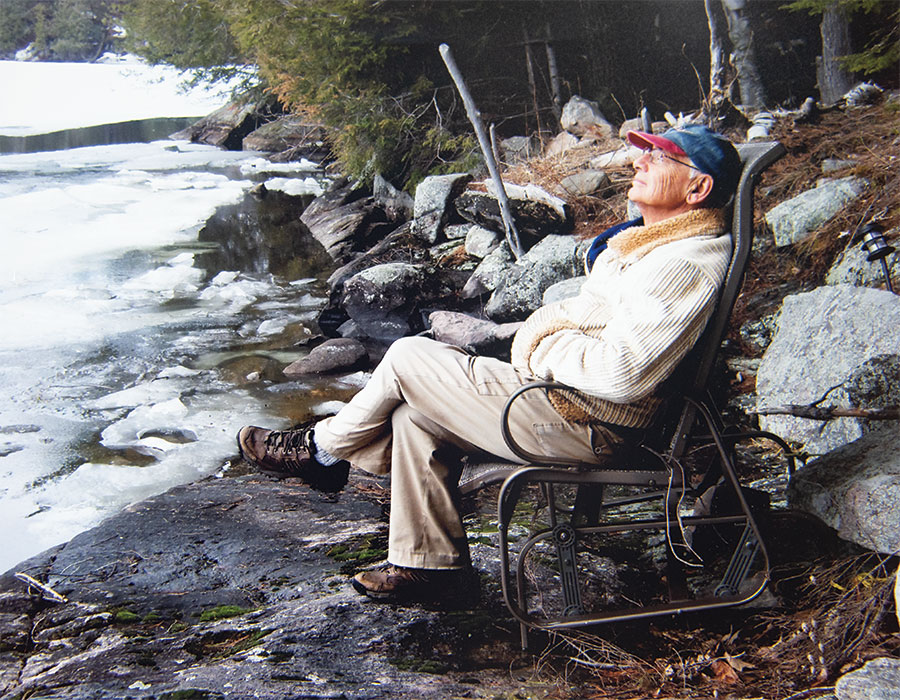

Paying attention can be draining, and I wonder if our conversations add too much heaviness. He can’t sit with difficult feelings, and his life has been bookended by depression. He was raised by a single mother who ended her arranged marriage while she was pregnant with my dad, and later married a man she didn’t love to make her son’s life better, so he felt huge pressure to choose the right partner. After my parents’ engagement, full of doubt and fear, he fell into a deep depression that lasted almost two years until after I was born. He believes he would never have married or had kids if my mother hadn’t stuck by him. In recent years, his dearest friends have died, aging has stolen pleasures like tennis and hiking, and the pandemic grabbed what was left — concerts, restaurants and visits from friends.

The depression is back in full force, manifested in exhaustion, and accompanied by statements like “I don’t want to be here anymore.”

He beats it back by watching online lectures; doing the crossword

puzzle (with questionable rules for what constitutes cheating); blogging about current affairs; reading the paper; requesting the foods he loves (last spring, he wanted Roda to risk her life during lockdown to get the ingredients for gefilte fish); and this project.

My dad’s favourite pastime is collecting people, learning their stories and telling them what to do. His family rarely appreciated the constant stream of visitors to the cottage, and his circle of friends is far more eclectic than mine. There was the lawyer who worked for a Saudi Arabian prince; a female commercial pilot; the Republican veterinarian who kept a pink gun in her purse; and his Spanish teacher, a Latina lesbian who brought her girlfriend along. He never overthought the combination of invitees. Differences in age, sexuality, politics, interests? Might they clash? Who cared.

He was not better behaved with friends than family, just more interested. He loved us, but unless we did something noteworthy, we just weren’t very bright and shiny.

The pandemic makes collecting new friends difficult, but re-collecting feels good, too. I tracked down Fiona Pie, an Australian news producer who still had her diary from a Nepal trek she did with Murray in 1991 when he was 60. He snored heavily, played annoying pranks, bought them all chicken dinner and kept up with the group, who were in their 30s. He was accosted daily by locals selling jewelry after word got out that he didn’t bargain and would pay the exorbitant starting price.

The staff had gone to great effort to bake the group a heavy cake, for which everyone but Murray praised them. “That’s not the way to do it,” he argued. “They’ll never learn to make anything other than crappy cake.”

“That’s rich, you hypocrite!” Fiona yelled at him. “How about your crazy spending spree?” He didn’t understand the comparison. His keen eye for faults applies only to others and, anyway, no one tells Murray what

to do.

I talked with his long-time friend Khaled, an Arab Israeli journalist he met in Jerusalem on a study trip, for whom he bought new laptops to help his non-profit; Tulla, who worked for Tennis Canada, where Murray funded a tournament for under-10s to build up the pool of Canadian talent; and an old friend, Helen, who told me his regular visits after her severe heart attack helped her survive. Everyone talked about his generosity and desire to help – it was never just lip service, although there was plenty of that.

Every conversation made me cry. I know these things about him, but they are often buried under layers of control, anger, demands and thoughtlessness. “But I’ve never done anything to hurt anyone,” he said recently. “Except open your mouth,” I responded. “Exactly,” he replied. At least he agrees.

Thankfully, memories beget memories. There was the time my dad pulled up at a bus stop in the pouring rain in his two-seater sports car and offered an older woman a ride. “I picked you up because you looked the coldest and the oldest,” he told her. (No filters.) That reminded my mom of a snowstormy night when she was pregnant with me. Three people were waiting a long time at the bus stop outside their building, so Murray invited them into their one-bedroom apartment where they had dinner and spent the night.

Every coin has a flip side: thoughtless/spontaneous, stubborn/reliable, nosy/caring, invasive/present. These stories compel me to turn each one over. My dad can still be an annoying asshole, but the bright side shows him in a new light.

I love that Murray is not simply the subject of a story others might read, but that he’s reliving outrageous, kind, funny things that have slipped his mind. Not usually one for sustained gratitude — since criticism is so much more satisfying — he has told me many times how happy he is that I’m doing this for him. But the gifts are mine, too. It’s rare to get this kind of time together, chatting and laughing about his life, their lives and my life, revising some long-held assumptions and diluting old, hurtful memories with lovely new ones.

A version of this article appeared in the Aug/Sept 2021 issue with the headline, “The Unvarnished Truth,” p. 67.

RELATED: