Malcolm McDowell Talks the New Canadian TV Series ‘Son of a Critch’ and the 50th Anniversary of ‘A Clockwork Orange’

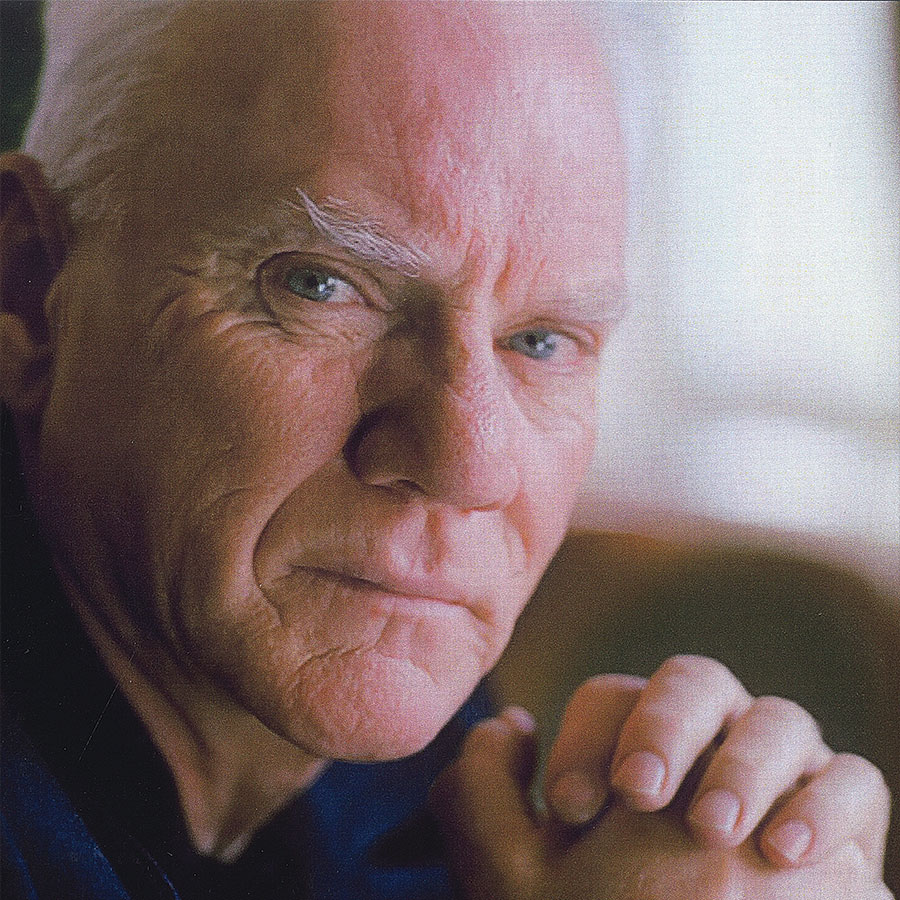

At 78, celebrated British actor Malcolm McDowell has numerous projects on the go — including starring in the new CBC series 'Son of a Critch,' a charming adaptation of 'This Hour Has 22 Minutes' alum Mark Critch’s memoir about growing up in 1980s Newfoundland. Photo: Courtesy of CBC

British actor Malcolm McDowell, 78, is perhaps best known for playing the gleefully vicious sociopath Alex DeLarge in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 A Clockwork Orange. But these days, he’s showing off his comedic chops as the mischievous grandfather in the new Canadian comedy series Son of a Critch.

Although raised in Liverpool, McDowell moved to California in the late ’70s and has lived there ever since. For our interview, the veteran character actor Zoomed in from an airy whitewashed room at the home he shares in Ojai, Calif., with wife Kelley, an architectural designer, and their sons Beckett, Finnian, and Seamus.

When I join the screen he’s mid-conversation, enthusing about the quality of high-definition video technology both in the new HD4K DVD release of A Clockwork Orange — marking the movie’s 50th anniversary this past December — and when watching his beloved Liverpool soccer team play.

“At Anfield yesterday,” he marvels of the screen detail, “I felt like I was at the stadium! You see every blade of grass. It’s a game-changer, it’s amazing.”

A Career With Range

From iconic franchises like Star Trek and prestige TV such as Mozart in the Jungle to indie films and playing memorable villains (see: Alex DeLarge, or his take on media titan Rupert Murdoch in the #MeToo drama Bombshell) — as well as decades of what could generously be called B-movies — the character actor has made a career of popping up in unexpected projects and places.

This month, for example, McDowell takes up the role of Pop in Son of a Critch, the CBC’s charming adaptation of This Hour Has 22 Minutes alum Mark Critch’s memoir about growing up in 1980s Newfoundland. The winsome, sharp comedy was filmed in and around St. John’s last summer and fall. And as McDowell’s an avid golfer, I ask if there was perhaps the added allure of hitting the links on the island. At this he laughs and notes that, even if there was, “it’s too damn windy.” His acting choices run as much of a gamut as his interests because, as soon becomes apparent, McDowell is man of enthusiasms.

“It’s all down to script,” he explains. He’d just had a “a lot of fun” making Truth Seekers with Simon Pegg and Nick Frost (think: a suburban English Ghostbusters) and when he was sent scripts for Son of a Critch, he liked the idea of a world-weary 12-year-old whose cultural touchstones are Don Rickles, Frank Sinatra, and Dean Martin rather than Atari and Van Halen. He told his manager to make it happen.

“I roared with laughter,” he recalls. “The character of Mark was so crazy. He’s an old man before his time in a 12-year-old’s body, going to Catholic school with all these severe nuns in charge.” Over the course of the series, the plot thickens. “Let’s say one of them, dear Sister Rose, I’m very … connected to,” he hints with a glint in those piercing blue eyes. “It’s quite something! But let’s not spoil it.”

In the show Mark (Benjamin Evan Ainsworth) shares a bedroom with his impish grandfather and that forges a unique bond between them.

“He’s like a father confessor, he’s like his psychiatrist,” McDowell says of the dynamic. “It’s pretty universal stuff and he’s such a great character. I mean, fancy taking a 12-year-old to a funeral home — for the sandwiches. Jesus!” he laughs.

“They’re all absolutely brilliant actors,” he adds of the cast, and praises Canada’s tradition of great performers and great comedians. At the moment, for example, McDowell is catching up on the work of the late Norm Macdonald on YouTube. (“What. A. Genius.” he says. “Holy God! Brilliant, brilliant.”)

Always Have Fun

The notion of fun comes up several times in our talk, McDowell’s final interview of the day (neither the decades of interviews nor this long press day of Zoom chats seem to have diminished the actor’s good cheer). And it only increases when I bring up British filmmaker Lindsay Anderson because, for all the buzz around A Clockwork Orange — admittedly the role that established him as an actor — McDowell has often said that it’s Anderson’s scathing 1968 critique of English society, if…., that “remains the most important film I’ve ever made, in terms of my career.

“He never really directed me” is how the actor puts it; “he chose me.” At this, he affects an airy accent that approximates Anderson explaining how 90 percent of a movie role is what actor you cast, and declaring McDowell to be a “Brechtian” actor: “You let the audience know that you’re acting, but you get them to believe you anyway.”

“Now, I never saw it as that,” McDowell says. “I always thought I was so far in the character! But there is a sort of gleefulness that when I work that I just enjoy — the work, I enjoy it! It’s sort of an infectious thing.”

He would go on to star in two more Anderson movies — and they had an enduring friendship, which he chronicled in a one-man show — but if.… unwittingly changed the course of his career.

“Stanley [Kubrick] saw it five times, he told me — he thought the film was absolutely one of the great films.” That’s why he was cast in the role for which he will always be remembered. “And now we’ve got, as you say, 50 years of A Clockwork Orange. It’s crazy.”

Turning the Clock Back on A Clockwork Orange

Every generation finds something new in A Clockwork Orange to appreciate. And McDowell’s own relationship with the controversial movie has certainly evolved over the years, from initially thrilled at the worldwide profile, to resentful of the shadow it cast on his career, to acceptance of it as a classic and, now, immense pride.

It remains a psychologically disturbing film, with darkly satirical themes and a prescient warning about antisocial behaviour and toxic masculinity that remain more relevant than ever. In this cultural moment, some aspects particularly resonate for its star. “We’ve just had the Trump presidency so: Big Brother,” he says. “I think the political aspect of the film is the one that has really kept new audiences coming back to it. The aversion therapy, stuff like that.”

The lead-up to the recent anniversary also includes A Forbidden Orange, a new documentary McDowell narrates (airing on TCM and HBO Max). It revisits the movie’s notorious first public screening in Spain, at a time when provocative cultural products were banned under the Franco government’s dictatorship. McDowell praises how A Forbidden Orange reconstructs and traces its importance in Spanish cultural history and, last October, McDowell travelled to Valladolid to attend the premiere.

“[Clockwork] meant so much to them, that it was shown — the lines were so huge people were sleeping on the pavement to get tickets to get in. It caused a riot! It was the most moving, extraordinary experience to meet them all.

“It’s an extraordinary piece of writing by Anthony Burgess,” he continues, and thinks the writer gets short shrift “because they all talk about Kubrick but actually it’s all Burgess, really. I’m not taking anything away from Stanley, he did a brilliant job translating it — the look, I mean.”

Here, McDowell shares a story about one of his many preparatory sessions at the filmmaker’s English country house. One night, after Chinese takeout, as they got to chatting about the futuristic feel of the movie, McDowell happened to have his cricket gear in the car and Kubrick suggested he don the white groin protector over his clothes, like a codpiece. (Likewise McDowell’s selection of a bowler hat, a potent symbol of middle-class respectability, whose meaning is subverted in the movie). And just like that, one of the most iconic and chilling costumes in movie history was born.

A Natural-Born Storyteller

It’s clear from our conversation that McDowell is an expansive and natural-born raconteur. And having watched Never Apologize, the 2007 filmed version of his staged monologue on his early career and friendship with Lindsay Anderson, I can attest he also has a wealth of great stories about luminaries, co-stars and friends such as John Gielgud, Helen Mirren, and Rachel Roberts (including a profanity-laced anecdote about Catherine Deneuve I can’t share here). I wonder if he might ever set them down in a memoir.

“I am!” he admits. “I’m gonna do it. I figured I’d done that one-man show — that’s half my life right there.” For the rest, he plans to work with a co-writer if he can manage to fit meetings in.

“I don’t have the time to literally sit down and write it [myself] because I’m literally — I’m going off to do this Netflix thing, I’ve got two movies in January, and then there’s another thing. And maybe back to Newfoundland if they like [Son of a Critch]. Off we go and the year’s gone!”

Vitality for the Ages

Not long ago the self-deprecating actor likened himself “an old fossil” in The Irish Times. But the dizzying number of upcoming projects, voice work (in animated series like Castlevania), narrating documentaries, and time on location shoots (in London for Truth Seekers or St. John’s for Son of a Critch) tell another story.

All the while, McDowell’s been sharing snaps on Instagram from shooting Moving On with Lily Tomlin and Jane Fonda—a movie from About a Boy’s Paul Weitz about two old friends who reconnect at a funeral and take their revenge on the widower.

McDowell, in fact, seems indefatigable. What’s the secret to his seemingly boundless curiosity, zest for life and many enthusiasms?

“I’ve got three young kids!” he laughs. “Five all told, my two oldest ones [with actor Mary Steenburgen, his ex-wife] are 38 and 40, and I’ve got 17, 14, and 12!”

Daughter Lilly is an actress and eldest son Charlie McDowell is also in the business — next up directing thriller Windfall; so is new daughter-in-law Lily Collins, star of Emily in Paris (she and Charlie wed last fall).

“Believe you me,” he continues, “I have no free time.” He does pause for a moment, long enough to proudly plug 17-year-old singer-songwriter son Beckett, and urge me to check out his new song “Weirdo” on Spotify.

And then he’s off.

Son of a Critch airs at 8:30pm (9pm NT) on CBC TV and CBC Gem.

RELATED: