Canadian Filmmaker Jennifer Holness Challenges Generations of Ingrained Narratives Around Black Women and Beauty in New Doc

Singer and activist Seraiah Nicole appears in the documentary 'Subjects of Desire', which premieres on Feb. 1 on TVO. Photo: Hungry Eyes Media

After they returned from school one day in 2017, Jennifer Holness overheard a conversation that two of her (three) daughters were having with their friends.

“They talked about being complimented on the things we as Black women have historically been ridiculed about,” the Jamaican-born Canadian filmmaker, screenwriter and producer related during a recent phone conversation in Toronto. “Things like ‘I love your butt’ and ‘Wish I had lips like yours’ and ‘Your skin is so perfect.’ My daughter is dark-complected; this was all shocking to me.”

Holness, now 53, adds that her first thought was “Black girls have arrived. But then my daughter told me ‘No, I’m actually not comfortable in my own skin, I don’t feel happy about it.’”

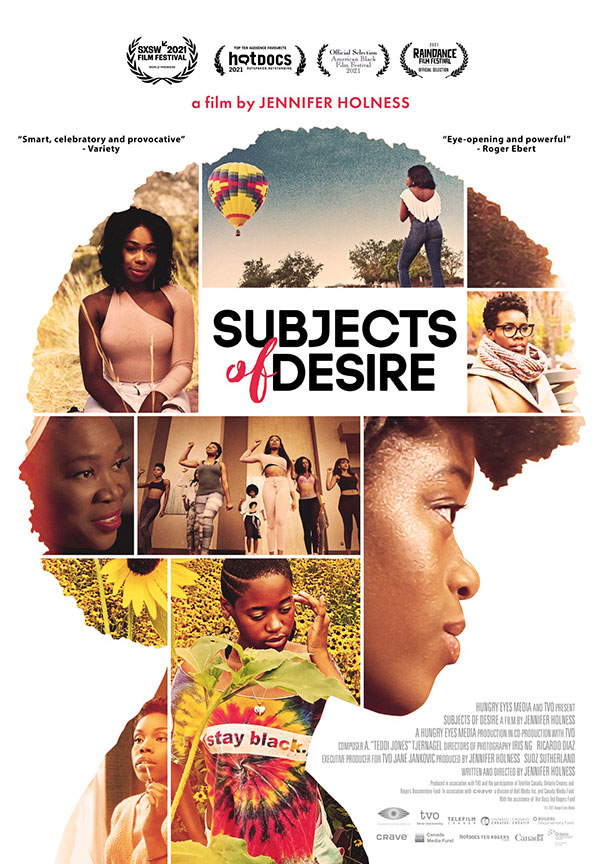

Thus started Holness’ journey toward her solo directing project — the feature-length documentary film Subjects of Desire, which challenges the harmful narratives around Black women and beauty. After winning awards and buzz on the film festival circuit — including TIFF in 2021 (one of Canada’s Top 10 films), Hot Docs (Top 10 audience favourites) and SXSW — the film airs on TVO on February 1 at 9 p.m. ET (and streams on demand on TVO.org and TVO’s YouTube channel).

The narrative wrap for the film became Black beauty pageants. When she learned the history of Miss Black America — that it was formed as a protest to Miss America in 1968, held a few streets away from the all-white pageant and with the famous (white) bra-burning feminist protest taking place on that street at the same time — Holness knew she had to film an anniversary event that encapsulated such polarizing views around beauty and race.

“I scraped together my pennies,” says Holness, “because I knew the pageant as protest was central to the story.”

She filmed footage of the Miss Black America pageant in 2018, then returned for principal photography in 2019; luckily she had somehow picked three top winners among the subjects she focused on initially for the film.

“People might disparage pageants, but Miss Black America serves a different purpose. For one thing, you have to really think about what I saw: different body types, women with kids. There was a bald woman. This pageant meets Black women where they are.”

There is a lie, she says, “that if you are beautiful it is not that important. But beauty is one of the most dominant forces in the lives of women, however you slice it, whether you like it or not. Your ability to succeed, if you are beautiful, is exponential.”

In 2019, there was a confluence among all five major beauty pageants — Miss World, Miss Universe, Miss USA, Miss Teen USA and Miss America — where all the winners were Black. It coincided with the kind of fetishization of traditional Black features in the broader culture that Holness’s daughters were talking about.

And then there was Rachel Dolezal, the white academic and activist who had been presenting herself as a Black woman despite having white parents.

“After she was outed,” says Holness, “I reached out to her right away. I wanted to speak with her before her Netflix documentary, because afterwards she might have been unwilling.”

The Dolezal footage in the film is riveting. “I didn’t dislike Rachel at all,” says Holness. “I thought that she took the wrong path. I think she loves Black culture, what she really needed to do was love the community.”

Another celebrity interviewee in the doc, American R&B singer-songwriter India Arie, also had compassion for Dolezal. “It’s sad, actually, because I didn’t feel like she was coming from a place of trying to gain anything,” she explains in the film.

But the beauty of this film is that it captures opposing views of anger at appropriation. Black culture, says Holness, is not a monolith.

“It is very hard for some Black women, because Rachel is inhabiting the skin of a very fair skinned Black woman, with features that are white. That is highly prized in a colourism world, when lighter complected is glorified, so you enter at the top of the food chain.”

Paradoxes and Stereotypes

The 2018 Miss Black America winner, Ryann Richardson, a tech entrepreneur based in New York, is another riveting voice in the film. “When I met Ryann,” says Holness, “she was so powerful, a very smart, strong woman. There was a moment when she almost cracked, let the vulnerability of how devastating that was and is for her.”

Holness is alluding to the moment in the film where Richardson got feedback from a judge that her look was “too ethnic.” Richardson realized, she said onscreen, that to win, she would have to learn to contour her face (to slimline her nose), straighten her hair in glossy waves. In other words, play the game through a white lens of beauty. She did. She won. And she had a lot to say about it all afterward.

To go deeper on these kinds of harmful paradoxes, Holness tapped academics to delve into the three predominant stereotypes of Black women in culture — the Mammy, the Jezebel, and the Sapphire.

The three stereotypes have been written about often, including by scholar Dr. Carolyn West. In the film, both West and Dr. Cheryl Thompson, an assistant professor at Ryerson University, Zoomer contributor and the author of Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture, break down the historical meanings.

Mammy, says Thompson, is the “benevolent South,” a plump, well-fed nanny sitting on the front porch rocking the children — an image that served white mainstream America from minstrel shows to household items to marketing campaigns. “I’ve had white women in my life acting as if I needed to nurture them.”

Then there is the Jezebel, the pervasive, slavery-era myth that Black women were hypersexual (and thus rape could not be criminal, went the tortured thinking). This historical lesson is intercut with a scene of young girls — two of Holness’ daughters among them — in a round table discussion, sharing about how people assume they can twerk and are promiscuous because they are Black. It’s heartbreaking. But as India Arie chimes in: “95% of Black artists have to play the Jezebel.”

The third stereotype, the Sapphire, comes from a character on the Amos and Andy radio show, and is the ever-moving target of the “angry Black woman.”

But the crux of the film is about the history of Black beauty standards within these stereotypical dynamics. Holness, for her part, relates her own hair story to me.

“I was a teenager, working at Shoppers Drug Mart. I got my hair braided, and I was so excited, I could finally ‘flip’ my hair. It took 5 or 6 hours to get it done. The boss immediately clocked me, said my hair was rude, and I could remove it or I didn’t have a job.”

Holness also says she learned a lot from Thompson about the history and context of Black beauty standards, and how they have shifted and morphed over time — from straightened hair being an empowering symbol at the turn of the century to a negative stigma from the 1960s onward.

“I didn’t want to just say Black hair is cool and funky. I wanted to understand where the standards came from. When you peel back the onion you always land right back in colonization and slavery. Nothing is benign.”

Holness, meanwhile, has a lot less time for the Kim Kardashians of the world, celebrating, “Diaper booty, fake lips and fillers and tan skin and the style very much comes out of Black culture.” Black women, she says, “have the same posterior and we have been ridiculed and rejected for it. You can’t just assign it because a white woman has it and is valuized for it.”

Then she issues a challenge: “I have very little patience for more of the Kim Kardashians, taking from Black culture. They have the microphone and the financial heft. But until Black women started to call her out, what have you done for the Black community?

“You like cornrows, fine, do the cornrows. But you better be standing up and supporting and putting investment into the Black community.”

Anchored in Local Black Culture

It was important to Holness to anchor the film in local Black culture as well. One of the most satisfying moments, she relates, was persuading Canadian R&B singer-songwriter Jully Black to be part of the film, calling herself a longtime fangirl of the artist. Black takes on the subject of blackfishing — white women artificially tanning or otherwise darkening their skin to look more Black.

There is, the film posits, a broad spectrum of appropriation, from Dolezal to the Kardashians to Ariana Grande to misguided Instagram “models” and “video vixens” — this last term the name for women who dance scantily clad in hip-hop music videos. But at the end of the day, if you can wash off your pigmentation, you can’t understand the experience of a Black woman.

Holness notes that she stayed and worked as a filmmaker in Canada “because of my kids and because I do believe in this country. It was a place that gave shelter to my immigrant mom and I’ve been able to spend my life working really, really hard. I want to make work that has parts of our story.”

She also says that, as a Jamaican-Canadian, “I was raised at the foot of America, because there was so little content in media for Black people, about Black people, in this country. Black Canadians: who?”

To that end, Holness, along with her husband, Canadian filmmaker Sudz Sutherland, through their production company Hungry Eyes Media, is co-producing BLK: An Origin Story. The four-part series, described on the Hungry Eyes Media site as “weav[ing] narratives from across the country and the globe – creating a magnificent tapestry that illustrates the invaluable contribution Black Canadians have made that has been ignored for too long,” — is set to air on Feb 26 on Global and the History Channel.

“The fact is Canadian Black history is powerful, and we know nothing,” Holness says. “The history [is] largely erased or unknown.”

Holness and Sutherland spent all of last year working on the series, and are putting finishing touches on it now.

Also on her resume: co-producing Stateless, a feature doc for PBS and the National Film Board about the plight of 200,000 Haitians living in the Dominican Republic being stripped of their Dominican citizenship, which won a special jury prize at Hot Docs in 2020. And she is producing the film Black Zombie, about “the evolution of the zombie from its origins in Haiti to its dominance in Hollywood, ultimately revealing its little known connection to slavery and movements of resistance” for CBC’s documentary channel.

Subjects of Desire, meanwhile, is a film that stays with you long after you finish watching it. The deft way Holness weaves together a historic base of understanding with real testimony and raw emotion from her wide range of subjects leaves you with a lot to think about, whatever experiences of your own you bring to the viewing.

RELATED:

Poet and Activist Maya Angelou to Become the First Black Woman to Appear on U.S. Quarter

Tributes Pour in for Sidney Poitier, the First Black Man to Win the Best Actor Oscar, Who Died at 94