‘The Porter’: Alfre Woodard Talks the New Series About 1920s Black Railway Workers and the Role She Was Excited to Play

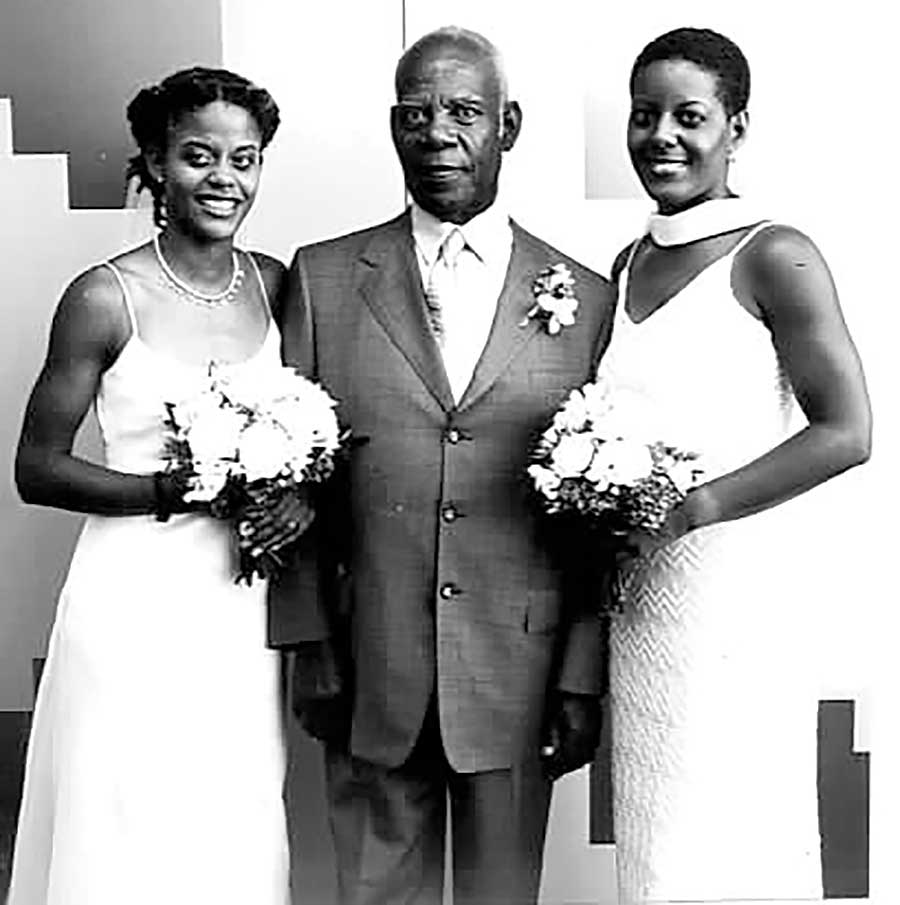

Alfre Woodard, 69, who originally signed on as executive producer of 'The Porter' — a position she called the "stealth Fairy Godmother" — ended up joining the show's cast after she carved out the perfect role for herself. Photo: Robert Ascroft/August Images

“This is definitely your story; it belongs to you, my sister,” Alfre Woodard enthused, when I told her that my grandfather worked on Canada’s passenger trains. The Emmy-winning American actor is an executive producer for The Porter, a TV drama about 1920s-era Black railway workers in Montreal. The CBC series animates tales my maternal granddad, Artley Charles Roach, who joined CN Rail as a sleeping car porter in 1965, shared about his quarter century of service. I wish I’d paid more attention and probed beyond the stories about cross-country sights, big tippers and celebrity encounters, like Sammy Davis Jr. buying rounds for passengers.

Until I read Cecil Foster’s 2019 book, They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada, I knew little about the history of the male domestics who made beds, cleaned toilets, shone shoes, and the meagre-paying jobs that improved their families, communities and country.

And I could never reconcile the shuffling, “yessuh” Hollywood, train-porter trope with our late patriarch’s leonine bearing, Holt Renfrew suits and the financial support he spread across the family.

The Porter, partly inspired by the Black Canadian Pacific Railway porters who fought to join the whites-only Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Workers, and the subsequent organization of the first Black labour union in Canada — the Order of Sleeping Car Porters, in 1917 — fleshes out how Black men challenged institutional racism on the railways, where they were overworked and underpaid.

The series also provides a broader examination of Black life in Canada during the ’20s, exploring romance, family life and artistic ambition against the backdrop of political and economic pursuits.

As executive director, Woodard was content to support the show as a “stealth Fairy Godmother,” but was reluctant to take an acting role. However, she was “floored” by the scripts. “Thank God. Somebody speaks my language in a way that I hear it, with the intelligence, with the humour, with the depth that I hear it,” she recalled during a Zoom interview from the brightly lit dining room of her L.A. home.

Comfortably chic in a long-sleeved, ivory tunic, pearly drop earrings and light makeup, Woodard was buoyant, chatty and teasing, with a pocketful of jokes about the Great White North.

“I’ve spent the majority of my time in Canada shooting, either [in] Vancouver or Toronto; that’s why I do poutine references,” she said mirthfully about her adventures on location here since the ’80s for movies like Scrooged, Down in the Delta and the current Apple TV+ sci-fi series See, which also stars Jason Momoa.

The Porter team proposed the Oscar-nominated performer, who has balanced a broad and prolific acting career with human rights work, play an associate of A. Philip Randolph — a real-life U.S. labour union organizer who inspires one of the show’s porters. But Woodard wasn’t interested in a high-minded character. “It’s easy to be an upstanding woman. Let somebody who really can work that do it,” she explained. “I only get dressed up for the stuff that requires thinking past the obvious. I said if I could play the 40-year whore, I’m in!”

So, Woodard, who turns 70 this year, is the fictional Fay, a pleasure-loving feminist, and the longest-working resident of a brothel in the St. Antoine neighbourhood of Montreal, known then as “Harlem of the North,” now Little Burgundy. She turns in a vivacious, scene-dominating performance, delivering the most risqué lines of the program, which premiered on CBC TV in February, is streaming on CBC Gem, and will appear on BET+ later this year.

The Porter, touted as the country’s biggest Black-led TV undertaking, educated the show’s doyenne about the history of the Black people in Canada. And she enjoyed the ensemble’s off-camera camaraderie.

“A lot of times, we end up just talking smack — I can’t say it for your upstanding publication,” the married mother of two jested about her synergy with younger colleagues. “And when we talk seriously, it’s usually about love, about relationships, whether they’re our partners, or our children, or, for them, parents. We very seldom have a sit-down about the business. I think they see me operate and [observe] how an actor can have control in a space where you’re really not given control; where you could be bleeding from the ears and [the director may say], ‘Just wipe it off, give her a cup of coffee. Okay, here we go.’”

This wasn’t the case with The Porter, which was shot in Winnipeg. The production modelled the inclusivity promised by the television and film industry in the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite movement and the George Floyd reckoning. Producers ensured at least one BIPOC member was hired in each department; a therapist was on hand for delicate scenes that employed the N-word or police callousness; and a cultural sensitivity consultant held bi-weekly Zoom meetings with cast and crew.

I’m not a fan of “When we was coloured” cinema; I find it about as entertaining as the roller coasters I avoid. Watching Roots as an 8-year-old in the late ’70s was petrifying. I can still recall the panic that groundbreaking TV series aroused in me: that on a whim, Black people could easily be enslaved again. So, I’m sparing about exposure to dramatized racial terror. But I do appreciate that efforts like The Porter are critical to a deeper understanding of Black history, and thankful that such programming is now often accompanied by trigger warnings and parental discussion guides.

The last survivor of 18 children, my grandpa, who retired from VIA Rail in 1990, didn’t play favourites among his four kids and 12 “grandpics” (pickney is Jamaican patois for child). He always had something delicious simmering on the stove, and a mint $50 or $100 bill to hand off, but was tight-lipped about his struggles and vulnerabilities. It is likely he benefitted from the courageous agitation of his forerunners, as explored in The Porter. After he emigrated from Jamaica to Toronto in 1963 with a basic education, within two years — and on the strength of portering — he purchased his first home in Toronto. That property and others netted a healthy sum when he died, benefiting his descendants in ways few Black men of his generation were able to do.

Woodard, on the other hand, grew up in Tulsa, Okla., where an estimated 300 residents of a prosperous Black neighbourhood were murdered and their businesses and homes razed in 1921 by a mob of white men. Woodard helped lead the 100th-anniversary remembrance ceremony for the Tulsa Massacre and also narrated a CNN documentary about it called Dreamland: The Burning of Black Wall Street.

The actor recalls how her interior designer father instructed her to be courteous to people in service, particularly railway workers. She learned that train porters — one of the best available jobs for Black men at the time — played an invaluable role as they travelled from city to city.

“The way that we think of the internet now, the porters kept everybody informed, connected, and that meant saving our lives most of the time, and all the way up into when I became active in the civil rights movement as a young teenager,” Woodard explained.

A five-decade veteran of the industry, Woodard has been a beacon for generations of the Black creative class. It was her young friend and See castmate, Canadian actor Nesta Cooper, who lobbied Woodard on behalf of the show’s co-creator, Arnold Pinnock, who was eager for Woodard to visit The Porter writing room.

“I didn’t quite get it,” Woodard said about the interest from the Black members of the series’ team — Pinnock, showrunners Annmarie Morais and Marsha Greene, and directors Charles Officer and R.T. Thorne. “You forget that people saw you [on TV] when they were little, and it meant something to them … We all grew up to be good, productive people in our societies, but we didn’t have images of ourselves on screen.

“When I got to Hollywood, I remember Sidney [Poitier] and them trying to get [a] porter story told 45 years ago. So you know, I’m excited about this one.”

The Porter is streaming on CBC Gem and will appear on BET+ later this year.

RELATED: