R&B Icon Deborah Cox, 48, on Her Canadian Music Hall of Fame Induction, Early Career and Why She’s Getting Better With Age

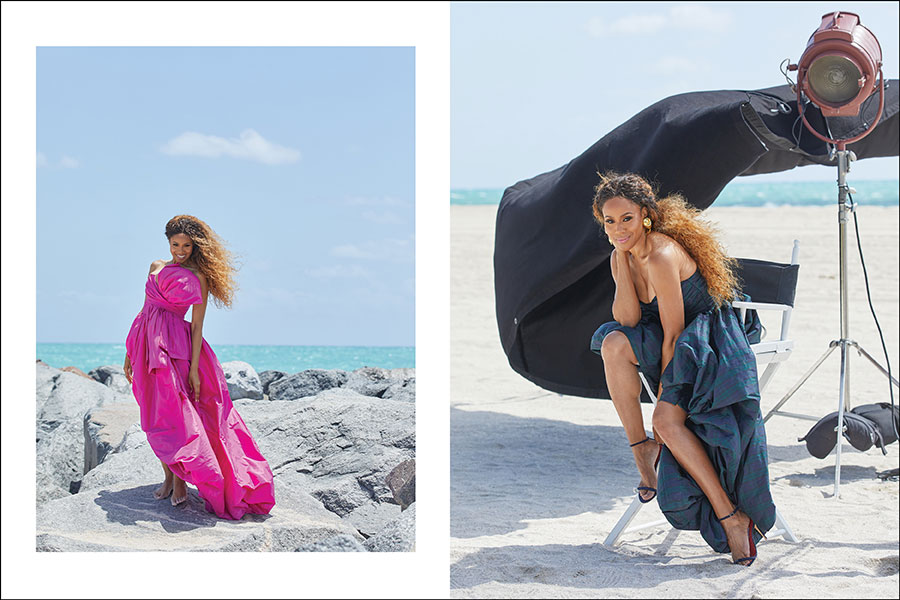

R&B Icon Deborah Cox — seen here during her recent Zoomer Magazine cover shoot — says her journey has made her realize "that it gets better as you get older." Photo: Gabor Jurina

Deborah Cox breezes into a swanky Miami restaurant on a quiet weekday morning looking like she stepped off the cover of a magazine. Imbued with the voice of a diva, but not the airs, Canada’s pre-eminent R&B singer, clad in a coral, body-skimming Michael Costello dress and chunky, coffee-coloured sandals, emits hints of the classic Guerlain fragrance, Shalimar. The 48-year-old is composed and accommodating, with an easy laugh and radiant skin.

Cox lives 30 minutes away in the South Florida home she shares with Lascelles Stephens, her manager and husband of 24 years, and their three children: son Isaiah, 19, who starts his second year of college this fall, and daughters Sumayah, 16, and Kaila, 13.

Today, the trailblazing songstress is a muted version of her glamorous onstage persona, notable for sparkling designer gowns and slinky catsuits, not to mention a powerful and dexterous contralto that is the envy of other vocalists.

The self-described “skinny girl from Toronto,” who didn’t let industry rebuffs in Canada deter her, went south and made it to the top of the R&B charts in America. She went head to head with Janet Jackson and Lauryn Hill, and became friends with the late Whitney Houston, who invited her to sing on the 2000 duet “Same Script, Different Cast”(a top Billboard dance club song).

She became this country’s first international R&B star, advancing the work of Liberty Silver — the first Black woman to win a Juno, in 1985 — and paving the way for Canadian acts like Melanie Fiona, Jully Black and 2022 R&B Juno winner Savannah Ré.

Cox has released six award-winning albums and 13 dance hits, garnering Junos for her first two albums, Deborah Cox and One Wish, and one for the 1997 smash single, “Things Just Ain’t the Same.” She also racked up two Soul Train Awards for her 1998 hit “Nobody’s Supposed to Be Here,” which spent a history-making 14 weeks atop the Billboard R&B chart.

Three decades into a steady, multipronged career, the newly minted Canadian Music Hall of Famer is enjoying an upswing of appreciation. Grateful for the accolades, she is still chasing her dreams, and her spine-chilling vocals are still strong and supple.

In late 2020, that rich, vibrant tone was the focus of an Instagram-spawned #DeborahCoxChallenge, with Grammy winners Fiona and Lizzo among the younger belters tackling the vocal gymnastics of “Nobody’s Supposed to Be Here” in a series of viral videos.

She also bantered with Los Angeles DJ D-Nice on Instagram Live during his Club Quarantine pandemic dance parties, which were a cool, celebrity-studded lockdown diversion. And last summer, he invited Cox to perform with him at the Hollywood Bowl, ticking off one of the venues on her bucket list.

This year she’s being “given her flowers,” adding a star of Canada’s Walk of Fame to her Hall of Fame induction. The phrase has become shorthand in the African American community as a way to honour achievement and recognize unsung contributions in the moment, and references a long history of overlooked Black excellence that often wasn’t acknowledged until the person was no longer around to enjoy it.

“Through this journey, I’ve realized that it gets better as you get older, and that you’re not running out of time,” the upbeat Toronto native says over an early lunch. “This industry tends to feed off of your insecurity, in making you feel like, as soon as you hit 40, that you’re over the hill. … No, you come into your own, even more so in your 30s and 40s and 50s. You really get it when you have a better understanding of what life is all about. You’re more mature in handling whatever your purpose is.”

At the Juno Awards this spring, she was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame by her Miami friend and former Toronto Raptor Chris Bosh, and lauded with a tribute video that included cameos by actress Angela Bassett, Canadian music producer David Foster (who declared, “We can’t wait to see what is coming next”) and singer John Legend, who called her “an incredible voice and incredible artist.” Cox, dressed in a stunning Elie Madi gown, delivered a show-stopping rendition of “Nobody’s Supposed to Be Here.” The powerful ballad is about finding love, but fans like Basketball Hall of Famer Bosh, who was inspired by the song in high school, say it’s motivational. At the Junos, he extolled Cox as “a true visionary, a Canadian whose songs touched the world and gave those who couldn’t speak a voice for themselves.”

The singer-songwriter’s empowering lyrics resonate with the LGBTQ community, where she headlines benefits, charities and pride festivals worldwide, and where anthemic remixes of her tunes have made her a dance-club darling. She has been recognized with multiple awards, including a special 2019 honour for visibility and leadership from the National LGBT Chamber of Commerce in the U.S., the same year she headlined Vienna’s Life Ball, Europe’s biggest HIV/AIDS charity event.

Cox grew up singing around the house she shared with her Guyanese immigrant parents and two sisters in Toronto. Influenced by the greats — Dinah, Aretha, Gladys, Tina and Whitney — she won talent contests, and honed her chops singing ad jingles, as well as gigging with local bands and supporting studio sessions. She excelled at the vaunted Claude Watson Arts Program at Earl Haig Secondary School and enrolled at Humber College, but when a teachers’ strike interrupted her first semester, the up-and-comer landed a spot in the Canadian production of the off-Broadway musical, Mama, I Want to Sing! and never returned to school. She went on to work as a background singer, first with Quebec pop sensation Roch Voisine, and then Celine Dion, whom she daringly left in 1992 to pursue her own career.

“The money was amazing, the experience was amazing, great hotels, just like this amazing life,” Cox remembers of the perks of travelling with the Quebec chanteuse and accompanying her on Jay Leno’s and Arsenio Hall’s late-night shows. “But I knew that it was going to take away from me doing my own thing, and I was starting to find my own voice. I just told her how sorry I was that I had to leave, and she was so gracious, because I knew she’d have to rehearse a whole other person. She was very supportive.”

The risk paid off. Within a year, Cox was living in Los Angeles, where she was signed to Arista Records by music impresario Clive Davis, who shepherded his protegé’s 1995 debut album to gold status — half a million in sales — and an American Music Award nomination for Soul/R&B New Artist (American neo soul innovator D’Angelo won).

She and Dion crossed paths again in 1997, when they were nominated for Best Female Vocalist at the Junos, and Dion won. The following year, they bumped up against each other on the pop chart, with “Nobody’s Supposed to Be Here” at No. 2, while Dion’s, “I’m Your Angel,” with the since-disgraced R. Kelly, held the top spot.

Cox, who had been turned down by every record label in Canada, found musical acceptance in the United States with the “warm and passionate” Davis as her champion, whose attention and commitment were refreshing. The industry giant, credited with fostering iconic talents like Houston, Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen and Earth, Wind & Fire, wrote letters to radio programmers and persuaded music execs to support and market Cox. Meanwhile, R&B music was floundering north of the border, even after Black Canadian artists like Portia White, Oscar Peterson, Salome Bey, Messenjah and Maestro Fresh Wes made advances at home and abroad with classical jazz, blues, reggae and rap.

“There wasn’t an infrastructure here, not just from a record company standpoint, but managers, agents, nightclubs, [venues] to play, television shows, radio programmers who would actually embrace that music,” explains music biz veteran Allan Reid, president & CEO of the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (CARAS), which oversees the Junos and Hall of Fame, in a phone interview from his Toronto office.

The “rejections became my redirection, and only added fuel to my fire,” Cox said in her emotional Hall of Fame acceptance speech. She is the first Black female recipient of the award, which was established by CARAS in 1978 for artists with many years of experience, and an outstanding contribution to the international recognition of Canadian music. Previous inductees include Alanis Morissette, Joni Mitchell, Sarah McLachlan and Shania Twain. Jazz legend Peterson is the only Black male awardee.

“I think that the Hall of Fame represents representation,” says Cox, who will get to mount her plaque this fall on the wall at the Hall of Fame’s home in Calgary’s National Music Centre. “It represents someone who, like myself, had to pave and take and carve out her own path. It’s validation.”

But, as singer-songwriter Mustafa noted in his 2022 Junos acceptance speech for the Alternative Album award, “being the first of anything should now be critiqued more than celebrated.”

Reid doesn’t flinch from the criticism. “I can’t change the past,” he says, “and nor can the people who are here doing this now. What we can do is address what’s happening now [and] in the future.” The Canadian music industry was “built on a singer-songwriter model that moved into pop and rock, that was primarily sort of a white industry overall for decades,” he adds. “So that’s also been our challenge when we look back at who’s been inducted by the Hall of Fame. The … majority [are] not diverse people, because that’s what the industry was celebrating.”

CARAS’s present-day efforts are evident. This year’s Junos, which also honoured Jamaican-born Denise Jones, the founding chair of the Reggae category, and the humanitarian work of Inuk singer-songwriter Susan Aglukark, also recognized a banner number of Black winners — more than a dozen — in a broad range of categories.

Although she has never stopped performing live, Cox hasn’t released a studio album in 14 years.

When I interviewed her in 2003, she was in the midst of professional and personal angst — finding her footing at J Records, which Davis started after he was pushed from Arista in 1999 — and expecting her first child, after years of debating the right time to start a family.

Cox had no qualms about following longtime champion Davis to his new label, but hung in the balance while the business was being set up and he prioritized Alicia Keys and Luther Vandross.

She gave birth to two children in three years and, seeking more creative control, went the independent route, starting her own label, Deco Entertainment, which put out 2008’s The Promise and yielded the Canadian hit “Beautiful U R.”

There are no hard feelings toward Davis; he appeared in Cox’s Hall of Fame tribute video, and she attended his 90th birthday celebration in New York earlier this year. In his 2013 memoir, The Soundtrack of My Life, Davis expressed regret that Cox “may have been burdened with too many expectations” as the “heir apparent to Whitney Houston,” even though he wasn’t grooming her for that type of “one in a generation” success.

“I’ve always felt some guilt that perhaps our initial aggressive campaign to get her debut album attention unintentionally invited unfair comparisons,” he wrote.

As her recording career plateaued and her family expanded, Cox, who made her acting debut in Canadian director Clement Virgo’s 2000 drama Love Come Down, turned to the stage — starring on Broadway six months after Isaiah’s birth — playing title roles in the Elton John musical Aida and the North American tour of The Bodyguard. In the stage version of the 1992 film about a sultry R&B singer starring Houston, Cox faultlessly soared through the tunes featured on the movie’s soundtrack, which sold 45 million copies. Her mic-dropping interpretations of songs like “I Will Always Love You” were evidence that, on the strength of her vocal range, power and resonance, comparisons to Houston were inevitable.

“I found other outlets to still do what I do and still have my sanity,” she explains. “It was really about trying to figure out what the happy medium was, and how to balance doing that and being in control, but also having a life.”

Cox, who has recorded new music but is weighing the right distribution deal, credits the musicals with preserving the control and purity of her voice.

“Because I’ve maintained my live performances, I’ve been able to just do what I need to do and still hit notes and with stamina, so I don’t get tired. Broadway was also the best training — six shows a week was no joke.”

Most recently, she has appeared in BET’s First Wives Club and the HBO MAX series Station Eleven, based on the bestselling post-apocalyptic book by Canadian author Emily St. John Mandel, which was filmed around the GTA during COVID. In the season finale, she turned in a riveting performance of Gladys Knight the Pips’ 1973 classic, “Midnight Train to Georgia.”

While Cox is enjoying the hometown commendations, she aims to use the retrospective embrace as a springboard for other projects.

Top of mind is a Black Canadian museum, which she is trying to get off the ground, and is in talks with partners and funders. “I want to recognize, and amplify, and give acknowledgement to musicians, artists — whoever has made their mark as a person of colour that hasn’t been given their flowers,” she explains.

Cox also wants to start a kids’ music program, similar to the Salvation Army sleepover camp that impacted her childhood.

“For me, camp was everything: It allowed me to get out of the city; it allowed me to just see something else,” she recalls. “Growing up, I felt very poor, very humble. My parents were really hard-working, but we didn’t have a lot going on. I want to be able to create an atmosphere where kids can have an outlet, and incorporate music and the arts in it as well.”

She is also mentoring young Black women like Toronto sisters Justice and Nia Betty, co-founders of Révolutionnaire, which began as a company selling “nude” dancewear in a range shades suitable for the various skin tones of people of colour. It has evolved into a design company with a Roots collaboration, as well as a social network for change makers. Cox serves as the brand’s ambassador, but is also a mentor and friend.

“The name Deborah Cox was one that was said so many times in our household, as an individual who was such an accomplished Black Canadian woman, who was very much a role model,” Justice, 25, says in a phone interview from Toronto. Cox gave Révolutionnaire a huge boost when she invited the siblings to the Hollywood Bowl show and introduced them to celebrities like D-Nice, Sheila E. and the Isley Brothers.

“Nia and I always feel so incredibly supported by Deb, whether it’s through phone calls, Zoom, text messages, regularly keeping in touch for quick questions, extended conversations, or just a fun laugh.”

It was critical for Cox to have her mother, who sometimes finds crowds overwhelming, in the audience for her Hall of Fame acceptance. “I really wanted her to take it in, because I saw the struggle growing up … her getting up in the morning — she’s been a receptionist, she’s worked at city hall, she has been a paralegal — she had many different jobs just to keep it going.”

The Junos appearance on Toronto’s Budweiser Stage — where she last performed for Lilith Fair in 1999 and Prince came backstage afterwards to pay his compliments — was a highlight of her career.“It was a whirlwind of personal emotions that I really didn’t get an opportunity to deal with, because I had blinders on to make sure that everything about the performance would go off well. I knew I was going to be very emotional and I’m not a very good singer when I cry.”

Cox saved her final comments at the Hall of Fame ceremony for her songwriting partner, BFF, soulmate and husband of 24 years. “There would be no Deborah Cox without you, Lascelles,” she declared. She credits his vision and encouragement for the breadth and longevity of her career. “He would see things more than I saw things for myself, and he would tell me the truth,” Cox says. “We allowed each other to grow, and I think that’s part of the reason why we’ve been together.”

Savannah Ré, who calls Cox a “Scarborough legend,” is equally inspired by the veteran’s personal life. “It shows that you can be successful and be in a relationship,” says the twenty-something Toronto-based singer, who married her frequent collaborator, YogiTheProducer, four years ago. “There’s definitely pressure on female artists especially, to have this single persona, like, ‘Oh, I’m available.’ So, it’s great to see that you can flourish in love and still be very successful.”

Cox and Stephens met in local Toronto bands, where she sang and he played bass. Blushing at the memory all these years later, she recalls being “mesmerized by his musicianship,” while he remembers being captivated by “of course, her looks,” but essentially her confidence.

“She knew who she was,” a low-key Stephens, in a rare interview, says by phone from their Florida home. “Vocally, she was always just killing it, but she was also up there playing the timbales like she was Sheila E. You couldn’t tell her nothing; she was banging those things.” With the lacklustre market for R&B in Canada, the pair headed south, shopping demos and meeting with executives until landing that fateful meeting with Davis. As her supporter-in-chief, Stephens is there for his wife professionally, as a motivator and buffer, and personally, to protect “her integrity, her light, her heart, her kindness.”

When she’s not on a film set or concert stage, Cox is at home, “riding my bike, hanging out with my family, just doing simple things, chilling out. I still play Scrabble, I still play Monopoly.”

Since she’s naturally slender, she doesn’t adhere to any rigid fitness routine. At lunch, she cleans her plate of lemon oregano chicken wings, and is game for dessert — any visit to Toronto means indulging in Crunchie bars, Glosette Raisins, dill pickle chips and and butter tarts. Even though she doesn’t order a glass, talk turns to wine, which she became interested in while touring wineries on days off in Europe. This year, she’s releasing her own organic French rosé, Kazaisu, sourced from Provence. The wine is named for her progeny, all of whom show an aptitude for visual arts, graphic animation and songwriting. The girls have sung background on mom’s records.

“Sometimes they’ll let us hear it, sometimes they don’t, but I’m not forcing or pushing them in any way,” says Cox of their creative output. “I want them to stay inspired and do it because they really love it, not because it’s something that I’m attached to.”

Although she wishes she “was able to spend a little bit more time in the early stages with them,” Cox believes she and Stephens have raised well-adjusted children while staying relevant in the entertainment industry, without having to compromise her standards — never mind the short-lived publicist who said her drama-free life was a marketing challenge.

“I just want people to know, and understand, that the joy that they see is really me being at peace, finally, with who I am, and my truth. I’m finally at that place where I don’t feel like I have to do, or be, anything more than who I am and what I’m doing.”

A version this article appeared in the August/September 2022 issue with the headline ‘Deborah Cox Gets Her Flowers’, p. 23.

RELATED:

Deborah Cox Receives Canadian Music Hall of Fame Induction at 2022 Juno Awards