Director David Cronenberg, 79, Master of the Macabre, On Resurrecting His 1996 Script For ‘Crimes of the Future’

Director David Cronenberg is back with 'Crimes of the Future,' a film he wrote in the '90s that explores a world where surgery is the new sex. Photo: Julien Lienard/Getty Images

I have an indelible memory of meeting David Cronenberg on a deserted stretch of Toronto’s Gardiner Expressway. It was after midnight. The elevated highway had been cleared of traffic and turned into a stage. Wrecked cars were artfully strewn along the tarmac. A crumpled Lincoln Continental lay on its back like a giant beetle, T-boned into the side of a bus, luminous under the stark halo of klieg lights. Stepping around the shattered glass and twisted metal, Cronenberg came over to greet me. “Welcome to my playground. It’s beautiful, isn’t it!” As the director surveyed his tableau, to the sound of a thousand starlings screeching from their nests above the Gardiner’s Stonehenge pillars, his eyes had the thrilled gleam of a thief in the night, an artist who had somehow persuaded the city to shut down a major artery for nights on end so he could make a movie about freaks who are sexually aroused by crashing cars.

That was fall, 1995. The following spring, Crash landed on the Cannes Film Festival like a firebomb, generating so much outrage that it won an unprecedented Special Jury Prize for “audacity, daring and originality,” over vehement protests from jury president Francis Ford Coppola. This spring, 26 years later, Cronenberg was back in Cannes, and once again everyone was talking about Crash as they braced themselves for his latest audacity, Crimes of the Future which envisions a world where “surgery is the new sex” — starring Viggo Mortensen as a performance artist who grows new internal organs that his creative partner (Léa Seydoux) slices out of his body for a live audience.

Cronenberg did his part to set the stage, predicting there would be walkouts within the first five minutes of his film. Fair enough: The opening scene shows an eight-year-old boy eating brittle pieces of a plastic wastebasket, then being murdered by his mother. But now that everything from Euphoria to Ozark is streaming sex and mutilation 24/7, it’s harder to shock an audience these days than it was in the ’90s. There were virtually no walkouts at Cronenberg’s première, which drew a seven-minute standing ovation and a largely warm critical response. “It was a great screening,” he told me afterwards. “No one walked out except me — I went out to have a pee.”

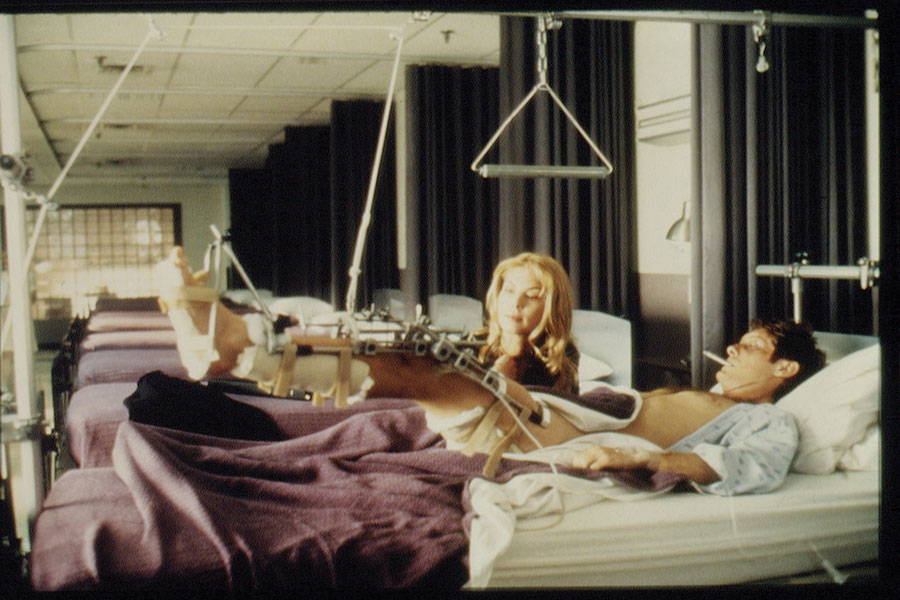

Despite some graphic scenes of squishy gore, I found there was something oddly comforting about Crimes of the Future. Like the best of Cronenberg’s work, it cocoons us in a lush netherworld of exquisite disturbance, where horrors of the flesh are delivered with panache, and underscored by a sardonic wit. And though it received no awards in Cannes, the film — his first in eight years — marks an invigorating return to form for the 79-year-old Canadian director. After half a dozen movies set in the “real” world (Spider, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises, A Dangerous Method, Cosmopolis, Maps to the Stars), this is Cronenberg’s first picture in more than two decades that takes place in an alternate universe of body horror — a steampunk dystopia so dank you can almost smell the mildew. It’s a noir world of dark waterfronts and peeling paint. And, like Naked Lunch, Dead Ringers and Crash, it revels in a ritualistic intercourse between the human body and a technological realm of creature-like devices.

If Crimes of the Future feels like a successor to Crash, that may be because he wrote the script the year Crash premièred. It was Robert Lantos, the veteran Canadian producer behind both films, who resurrected it. “David had assured me many times that he would never make another movie,” recalls Lantos, who came across it several years ago and suggested he re-read it.

Cronenberg says, “It was like suddenly being handed a script that somebody else wrote and thinking, ‘Yeah, this is pretty good. How are we going to make it?’” The script was a first draft, “but I didn’t change a word of dialogue,” says the director. What did change was the location, which was shifted to Athens, because filming in Toronto was too costly. “I thought, ‘Okay, I love the idea of Athens and I’m going to embrace it.’ And I’m open to discoveries, because, as always, movies involve found art.” While there’s barely a glimpse of Athens in the film, the first shot shows the rusted hulk of a ship on its side, a totem of environmental ruin, as the plastic-eating boy plays on the Aegean shore.

The notion of a child being nourished by microplastics “is partly satirical and partly a possibility,” says Cronenberg. “Nobody was talking about microplastics 20 years ago. Now, we know there are bacteria that use plastic as fuel and protein. We are made up of single-celled animals that could do the same.” Kristen Stewart, who co-stars in the movie, said in Cannes that she was taken aback when the director told her he wrote the script in 1996. “I was like, ‘Oh, cool, so you’re a frigging oracle.’” Cronenberg demurs.

“It’s very sweet of Kristen to say that,” he tells me. “But if I’m an oracle, it’s by accident. Art is not prophecy. That’s not what it’s for. For me, it doesn’t matter if something I predict in a film comes true or not. I wasn’t trying to predict the internet when I made Videodrome.”

While the arteries of Cronenberg’s body of work appear as interconnected as the Marvel Universe, he says he never thinks of previous films while making a new one. “If the film fans find those connections, that’s fine. But creatively, it gives me absolutely nothing. I only think about the movie in its particular bubble — how do I bring these characters to life?”

Still, lifelong collaborators such as production designer Carol Spier and composer Howard Shore forge a familiar connective tissue throughout his work, along with recurring actors like Mortensen and Jeremy Irons.

After helping rejuvenate Cronenberg’s career in A History of Violence, Eastern Promises and A Dangerous Method, Mortensen performs his fourth tour of duty as leading man in Crimes. He plays Saul Tenser, an avant-garde celebrity afflicted by untold ailments, whose body is manipulated as he sleeps and eats, cradled in organic contraptions that contort his body — the tentacled “OrchidBed” and a bone-like massage device called the “Breakfasting Chair.” The ultimate tortured artist, Saul meets his match in Seydoux’s character, Caprice, a loving partner in crime, who performs surgery on him in a sold-out operating theatre of voyeurs with vintage cameras. Amid the spectacle, there’s a constant chatter of witty dialogue, from Saul’s complaint that “this bed needs new software — it’s not anticipating my pain” to sweet nothings, like “I want you to be cutting into me.”

It’s a film that makes everything a metaphor for everything: sex and surgery, art and death. It’s a portrait of the artist as an old man, and Saul struck me as a closer surrogate for Cronenberg than any of his previous protagonists. “Viggo has gone on record as saying he thinks this is my most autobiographical movie,” he concedes. “I’ve never had my stomach cut open, but I think he’s talking about what you’re talking about.” Mortensen’s character, he says, “is the model for me of what it is to be an artist and a filmmaker. You are really giving everything you’ve got, inside and out, to your art, and offering it to your audience. It can be painful and it can make you very vulnerable. You are exposed, literally and figuratively.” It takes guts to be an artist.

The film (now in rep theatres and on streaming services), was not cast as planned. Mortensen initially coveted a smaller role as a detective. “I had to really harass him to convince him that he should play the lead,” Cronenberg says. Natalie Portman was set to co-star as Caprice, while Seydoux was cast in a smaller role as Timlin, a bureaucrat in a secret government branch called the National Organ Registry. When Portman dropped out due to a scheduling conflict, Seydoux asked to take on her role. Cronenberg’s response: “Yes, you are the actress I was looking for all along!” Kristen Stewart, perversely cast against type, replaced her as Timlin, a self-effacing fangirl who, along with her wild-eyed colleague (Don McKellar), is star-struck by the legendary Saul.

“Sometimes, the right people say ‘no’ and strange casting things happen,” Cronenberg muses. “Sometimes you have to get lucky.” Seydoux, who lit a fire under Daniel Craig’s 007 in No Time to Die, enriches Crimes of the Future with layers of emotional intelligence, delivering the strongest performance by an actress in a Cronenberg film since Geneviève Bujold in Dead Ringers (1988). “Both Viggo and I were really impressed with Léa,” he says. “The other thing was that she and I got along incredibly well and we are now fast friends. That doesn’t have to happen for someone to give a great performance — that the director and the actors become friends. But it’s wonderful when it does. We became very close that way. We talked about all kinds of things, not about cinema. Never about cinema.”

Throughout his career, Cronenberg has been fixated on the existential fact of mortality. Now that he’s approaching 80, it’s not just an idea. “How do you live in the face of it, if you’re not religious?” he asks. “How can you actually live, accepting the inevitability of your own oblivion? That’s always there.” After not making a movie for eight years, the director worried if his body was up to it. “You need a lot of stamina. The hours are murderous and you don’t get any sleep and the pressure and intensity are huge. But gradually I found that, yeah, I can still do it. Age was not a problem.”

Crimes of the Future is the first movie he’d made since the death of his beloved wife, Carolyn, the mother of two of his children, in 2017. “We were together for 43 years and it was paradise, honestly. So, it’s Paradise Lost, there’s no question.” Her death, he says, did not have “a direct impact” on the themes of mortality in his new movie. However, his next film, a thriller called The Shrouds that was announced in Cannes, “will be much more directly about Carolyn’s death.” It will star French actor Vincent Cassel as Karsh, an innovative businessman and grieving widower who builds a device inside a burial shroud to connect with the dead. According to the film’s synopsis, when several graves in Karsh’s cemetery are vandalized, including his wife’s, he’s driven to “re-evaluate his business, marriage and fidelity to his late wife’s memory, as well as push him to new beginnings.” Beyond that, the director would not elaborate.

Lantos, meanwhile, is hoping to produce a film of Cronenberg’s 2014 novel, Consumed, a surreal extravaganza of sex-tech fetishism that involves cannibalism, Cannes and North Korea. “That would be an ambitious project,” he says, understating the case. “It will get made when he’s ready to do it.”

Cronenberg seems to be in no rush. “The one thing that I have at this age, that I didn’t have when I was starting out,” he says, “is the equanimity of not really giving a f–k. I’m not desperate to make another movie at all. That gives you a peace and tranquility that only experience and age could give you. I’m just floating along.”

A version this article appeared in the August/September 2022 issue with the headline ‘Cronenberg Classic’, p. 56.

RELATED: