James Bond at 60: From Clothes to Cars, Charting 007’s Timeless Style

Dressed To Kill: Daniel Craig in 2021’s 'No Time to Die,' his final turn as 007. Photo: Collection Christophel/Alamy Stock Photo

On Wednesday, James Bond actor Daniel Craig, 54, joined a roster of 007 alumni at a London party to mark the 60th anniversary of the release of the first ever Bond film, Dr. No. Given the bash was thrown by Omega watches — which provides the celebrated spy with his timepieces — we’re marking Bond’s 60th by taking a closer look at six decades of 007’s style.

Fine lines and wrinkles, uneven skin tone, weakened muscles. Some of us know what it’s like to hit 60. The wear and tear that sends sexagenarians stampeding to yoga classes and plastic surgery clinics is inevitable, unless, of course, you are James Bond.

But let’s leave aside 007’s dazzling physical attributes, like the jaw-dropping six-pack Daniel Craig brandished in the “shirtless” scenes, which have proven to be highlights of his Bond films ever since he flaunted a skimpy pair of sky-blue La Perla trunks as he emerged from the sparkling Nassau surf in his 2006 debut, Casino Royale. (And if you are anywhere near 60, or over, consult a physician before testing the “military boot camp” fitness regimen devised by British personal trainer Simon Waterson to keep Craig, and his Bond predecessor, Pierce Brosnan, in fighting shape.)

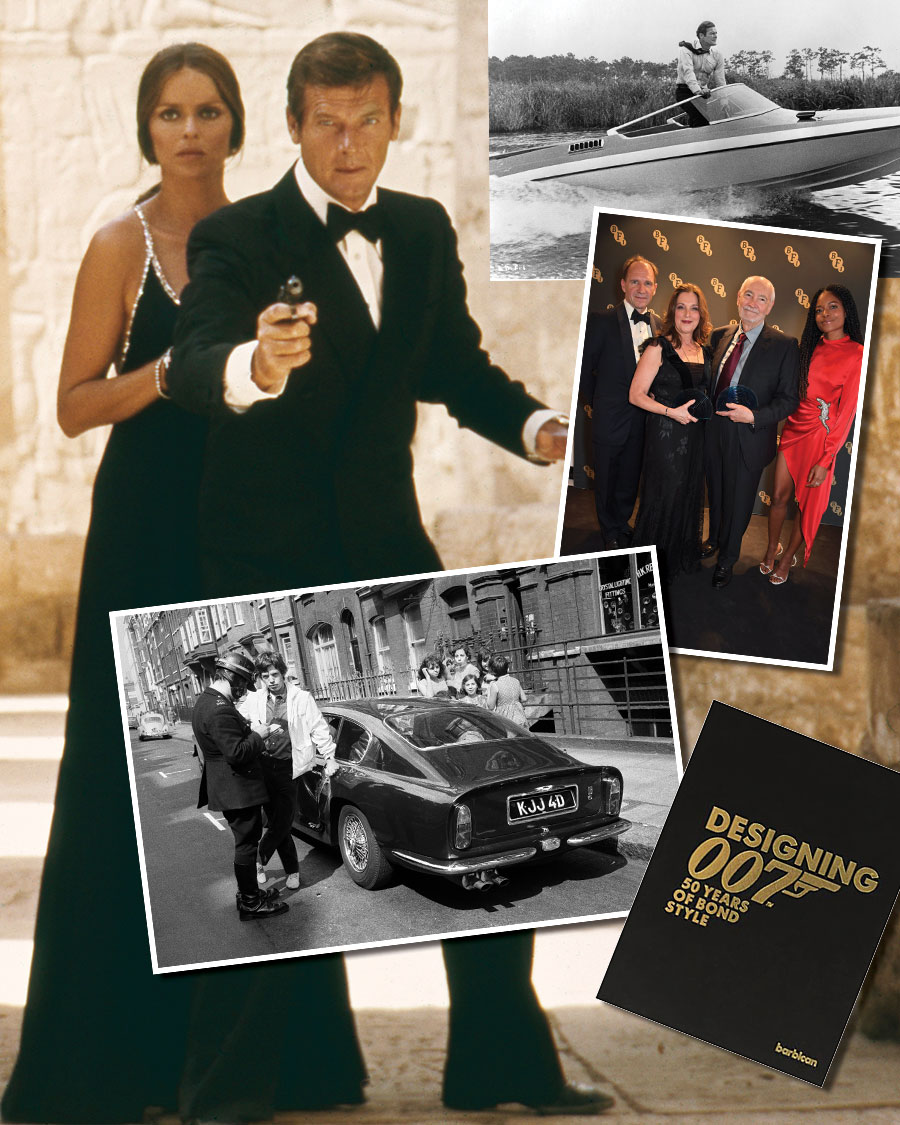

Consider, instead, why the mythical MI6 officer featured in 25 films never gets old, even as Britain’s EON Productions commemorates the 60th anniversary of 007 films with special events, from a Christie’s auction of cars, props and wardrobe items culled from its extensive archive to a British Film Institute (BFI) series of screenings — including the première of Mat Whitecross’s music documentary, The Sound of 007 — plus talks with EON producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson, who are maternal half-siblings.

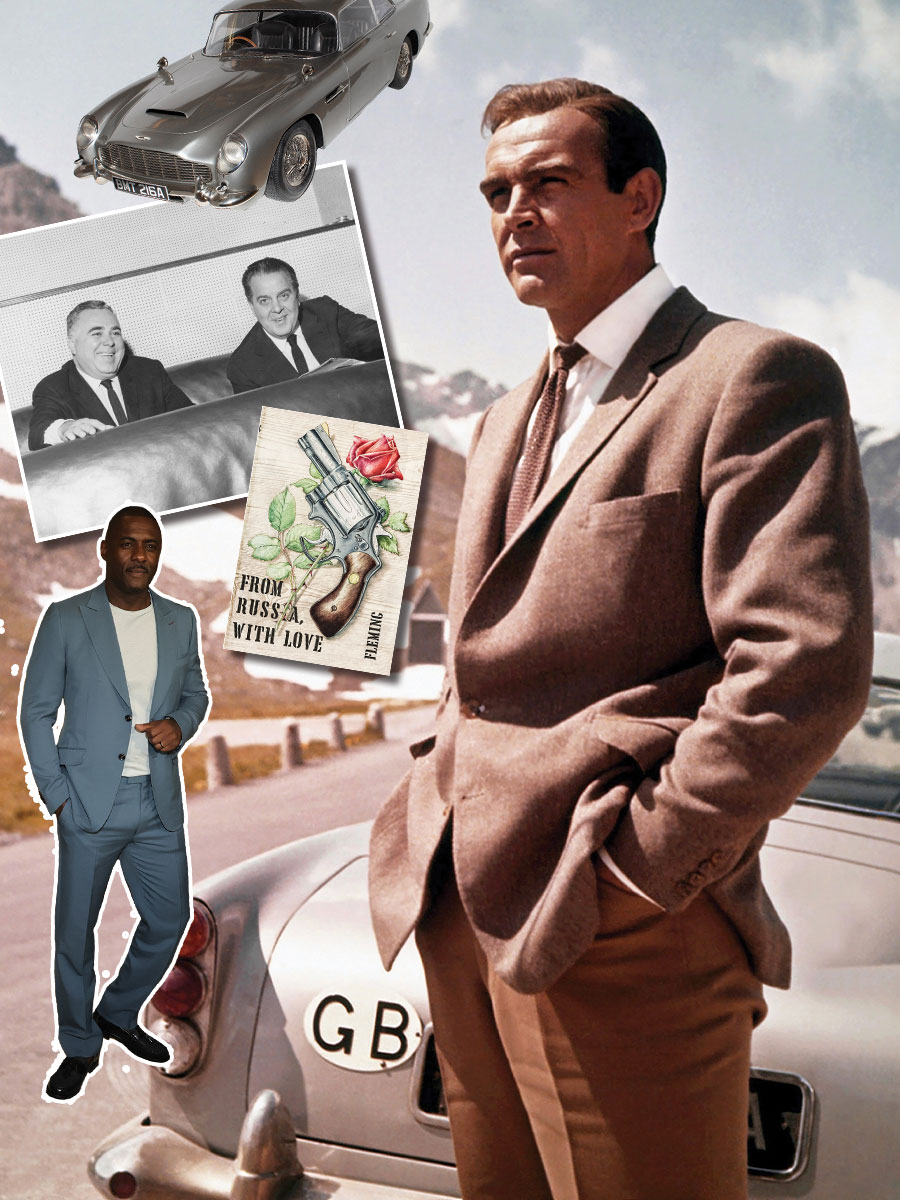

Production on Bond 26 is at least two years away, “if not longer,” Broccoli told Deadline magazine in June. Nevertheless, the scuttlebutt that has circulated since Craig announced the end of his 15-year run on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert in November 2019 is heightening anticipation for the next spy thriller and maintaining Bond’s relevance. The heartthrobs said to be vying for the role include Tom Hardy, Chiwetel Ejiofor and Regé-Jean Page. Reports that Idris Elba has “walked away” from talks are as frequent as tabloid headlines charting his chances as a frontrunner in the hotly contested acting race. “It’s a reinvention of Bond,” Broccoli has promised.

No matter who has portrayed the secret agent or his cohorts, 007 films radiate an inimitable escapist quality, and have a unique ability to seduce the senses. The finely tailored clothes, the sleek automobiles and sophisticated gadgets — as well as the exotic far-flung locations that Bond explores on his missions — contribute to our enduring fascination with the 007 films.

The original Bond producers, Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman established painstaking craft as a Bond film tradition. They spared no expense to get every detail of a 007 film exactly right, signified by the name of the company they founded in 1962, Everything Or Nothing (EON). Their no-holds-barred approach translated to the screen the alluring fantasies Ian Fleming conjured in his Bond novels — and extended to the luxe book jackets. (After Fleming’s wife, Anne, noticed Richard Chopping’s artworks at London’s Hanover Gallery in 1956, the author and the painter worked together to conceive startling cover imagery for nine of his bestsellers, beginning with From Russia, with Love.)

Broccoli, a bon vivant, was an Angolophile (like the Sherbrooke, Que. born Saltzman), who got his start in 1930s Hollywood. Back then big studios like MGM and legendary producers such as Sam Goldwyn and Jack Warner made glamorous box office hits by pairing their finest in-house production talent with renowned artisans like Coco Chanel, Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí.

Importing this collaborative workmanship to British moviemaking launched the style traditions that have always set Bond films apart. Typically, for example, only megastars like Audrey Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich and Cary Grant (Broccoli’s dear friend, best man and his first choice to play Bond, although Sean Connery nabbed the part after Grant declined it) could command a Hollywood studio to use their preferred couturier or tailor to make a screen wardrobe, simply because of the expense involved in the production. However, costumes for Bond, his adversaries and female sidekicks — as well as his gadgets and vehicles (cars and boats included) — have always resulted from special relationships between filmmakers and gifted design professionals. But like most partnerships, the early ones required some heavy lifting.

Equipping Bond with the “most famous car in the world,” as his silver Aston Martin DB5 became known after it debuted in 1964’s Goldfinger, began as a discussion involving the film’s director, Guy Hamilton, its production designer, Sir Ken Adam, and special effects artist John Stears. (Known as the “real Q,” Stears won Oscars for Thunderball and Star Wars.) The trio reasoned that because “Fleming’s novel specified a gadget-laden Aston Martin,” it seemed natural for Connery to be behind the wheel of the British-made sports car, as U.K. film historian Paul Duncan noted in his 2012 book, The James Bond Archives. It was “the most expensive and sexy British sports car of the period,” Adam said in an interview about Ken Adam Designs the Movies: James Bond and Beyond, published in 2008 by author Sir Christopher Frayling.

Executives at Aston Martin were “sort of half interested,” Stears recalled in The James Bond Archives. Bond films were crowd-pleasers after Dr. No inaugurated the series at the London Pavilion in October 1962. Critics, however, were lukewarm, until Goldfinger (the third in the series) turned the tide and became the series’ first action blockbuster. The film recouped its $3-million production budget two weeks after its September 1964 release, and became the fastest-grossing motion picture of all time.

Building the Aston Martin, which contributed to Bond’s clout, was as nail-biting a process for Stears as the mesmerizing chases the slick silver car has conquered ever since it tore up the screen in Goldfinger. “It was terrifying — there were no standbys,” Stears said in The James Bond Archives, remembering how he equipped one Aston Martin DB5, which the company eventually relinquished, with the iconic features that inspire awe and laughter: revolving tire slashers, a smokescreen and the ejector seat, among others. “If that car had broken down, we’d have been in deep trouble,” he admitted in Ken Adam Designs the Movies.

Connery’s finesse behind the wheel inspired Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Mick Jagger to acquire their own DB5s. “Aston Martin’s sales went up by about 60 per cent,” remembered Adam. “We had no problems getting cars from anybody!”

I studied Adam’s work as the curator of Designing 007: Fifty Years of Bond Style, a touring exhibition commemorating the series’ 50th anniversary in 2012. Reflecting on the seven Bonds he helped to make — including Roger Moore’s romps, The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker (which are two of my favourites) — Adam reasoned that 007 films endured because they were always “one step ahead of contemporary.” Like Goldfinger, they showed audiences fine luxuries that were ahead of the curve — in other words, “next” rather than “now.” Adam’s words came to mind when I caught a New York première of Bond 25, No Time to Die, last year.

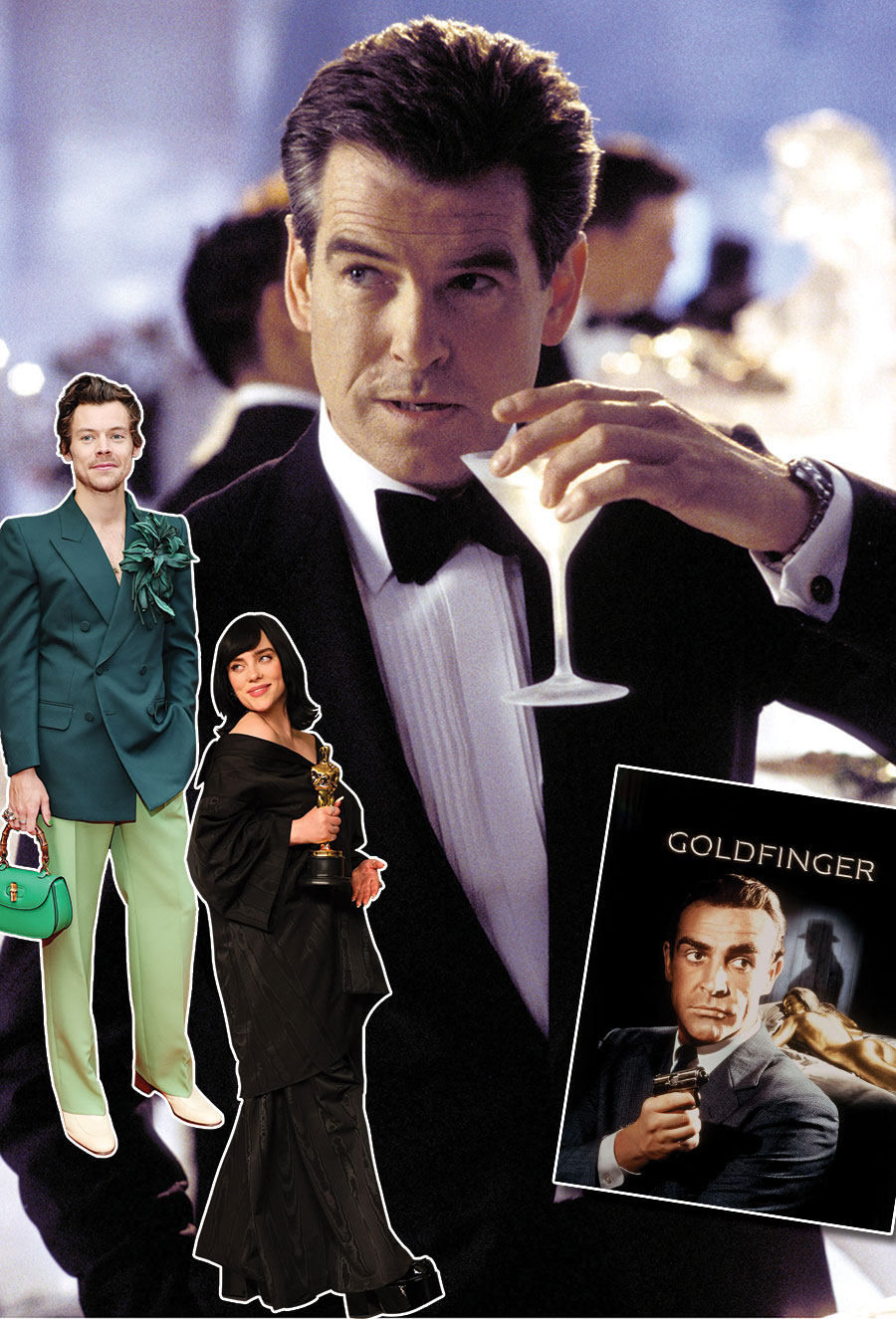

There’s a lot to admire about the film: Cary Joji Fukunaga’s perfectly choreographed combat sequences and blistering car chases; the explosive “barrage of bullet fire,” which visual effects master Chris Corbould masterminded for the opening’s DB5 ambush sequence; the Oscar-winning pop-ballad theme that combined Billie Eilish’s heartfelt vocals with Hans Zimmer’s moody orchestration.

The concrete-clad headquarters, which the film’s production designer, Mark Tildesley, created for Rami Malek’s Lyutsifer Safin, references the Brutalist wonders Adam dreamed up, like Spectre’s Volcano Lair in 1967’s You Only Live Twice and The Spy Who Loved Me’s submarine station in Karl Stromberg’s fictional underwater citadel, Atlantis. The 350-tonne, glass-domed Sphere Building, which architect Renzo Piano designed to house the David Geffen Theater at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, owes something to Adam’s handiwork, too.

It was remarkable to me how the two-year delay of No Time to Die’s release meant that it opened just as professionals around the world were grappling with COVID-19 re-entry in the fall of 2021. Yet there was Bond, on the cusp of change as usual, easing his way out of his own “great resignation” — namely, his early retirement to Jamaica. As many of us were still lounging around in sweatpants, Bond was getting back to work, alternating relaxed casuals by Rag & Bone with his signature Tom Ford suits. Bond’s No Time to Die look is perhaps the most freeform style that any 007 has yet sported on screen, although it was perfectly in tune with the eclecticism that characterized post-pandemic dressing.

“The thing about Bond films — what preserves them and makes them endure — is that they are always steps ahead, and yet they are timeless,” says Suttirat Larlarb, No Time to Die’s costume designer, in a Zoom interview from New York. “Bond always leads the way.”

It’s impossible to predict where Bond will go next, who will fill his shoes or if his shoes will be made by Crockett & Jones, the venerable English cobbler who shod Craig. The 007 productions are always shrouded in secrecy, which means that even “insider” reports fuelling tabloid websites are unreliable. Craig’s shoes, however, are huge ones to fill. His final three Bond films generated the series’ highest box office takings. In order of rank, they are 2012’s Skyfall (the first Bond film to gross over US$1 billion), 2015’s Spectre and No Time to Die.

Barbara Broccoli has confirmed that Bond will remain male. “We are the custodians of this character,” she explained in a 2020 interview, alluding to how EON strives to maintain the identity Fleming created for 007. She has also said that Bond should be British, “although British can be any [ethnicity or race],” she told The Hollywood Reporter.

Even if Bond films are ageless, the next 007 has to be young, given that EON has confirmed a deal with Warner Brothers to produce the 007 series until Bond’s 75th birthday in 2037. (That gives a newcomer the chance to complete a 15-year stretch like Craig, who is the longest-serving Bond.)

Ever since I watched Harry Styles’ big-screen debut in Christopher Nolan’s Second World War drama, Dunkirk, I’ve always thought he’d make a great 007. The 28-year-old has proven he’s a film star in the making, with two movies coming out this year — the psychological thriller Don’t Worry Darling and the romantic drama My Policeman — and a cameo as Eros in the Marvel Studios film, Eternals. He shares a gift with Sean Connery — who, according to a 2021 survey, ranks as the best Bond of all time — in that Styles has an alluring physicality and a coiled grace.

In the 2019 book, When Harry Met Cubby: The Story of the James Bond Producers, author Robert Sellers recounts how the years the Scottish actor spent in movement classes paid off when he exited his first meeting with the producers. “Both men rushed to the window to watch him leave the building and cross the street. It was the way Connery moved that clinched it, for a big man he was light on his feet, like a big jungle cat.”

Styles certainly has the swagger and a palpable charisma, and he could rock the suits and handle the Aston Martin. The question is: How does he take his martini?

A version this article appeared in the October/November 2022 issue with the headline “Bond Ambition,” p. 90.

RELATED:

Who Will Be the Next James Bond? Producers Mull Choice as Film Franchise Turns 60

No Time to Die: Tracing James Bond’s History in Jamaica as 007 Makes His Return to the Island