Follow The Ink: A Writer Stumbles Into Filmmaking, Only to Decide It’s Not the Definitive Third Act

Foraged inks drying in custom dishes made by Toronto’s Akai Ceramic Studio. Photo: Lauren Kolyn/ Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada and Sphinx Productions

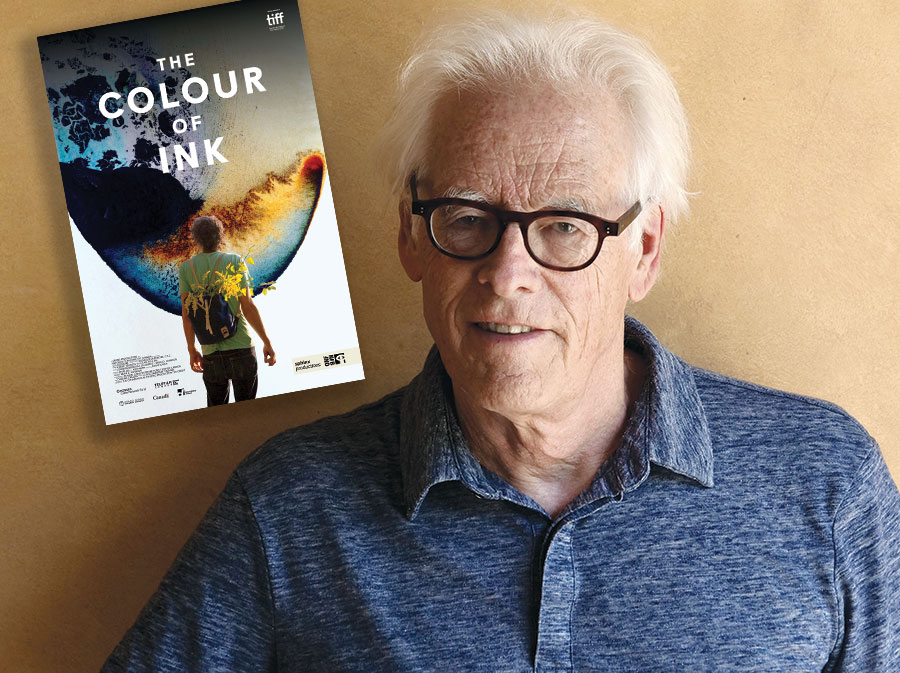

Whenever I’m asked why I wanted to make a movie about ink, I draw a blank. Even now that The Colour of Ink is a tangible thing — its theatrical release in six Canadian cities launches (in Toronto) on March 23, seven years after I began shooting it — the fact that it exists still baffles me.

True, I’ve made my career working with ink, as a young reporter scribbling notes and hammering the carbon ribbon of a typewriter in a Montreal newsroom, and then graduating from newsprint to magazines, where the ink didn’t come off in your hands. But like most writers, I never gave the stuff a second thought. The words were all that mattered.

Ironically, it was the digital revolution that led me back to ink. One summer at a log cabin on a lake, I discovered the video button on a little point-and-shoot camera and began editing on a computer using iMovie, the gateway drug for a generation of amateur filmmakers. As I upscaled to camcorders, I got hooked. Long before YouTube and TikTok, I had no idea I was riding a wave that would turn anyone with a phone into an amateur auteur.

After three decades of writing about the arts as a journalist and film critic for Maclean’s, I didn’t go looking for a career as a filmmaker. Films found me by happenstance, one after the other. I stumbled across the subject of my first documentary feature, Al Purdy Was Here, 10 years ago when my wife, writer Marni Jackson, asked me to cut some archival footage of Purdy for a benefit concert to restore the poet’s A-frame cabin as a writing retreat. The Purdy film led me directly to The Colour of Ink, at the foot of the poet’s bronze statue in Toronto’s Queen’s Park.

While I was shooting an interview about Purdy with Margaret Atwood, she informed me that the statue had a Twitter feed, which posted random observations of whatever it “saw” from day to day. (The squirrels are on the move again . . . someone left half a can of Sprite for me.) “We don’t know who it is,” said Atwood, but she’d been following the statue’s tweets for months. That evening, at a reception for the Griffin Poetry Prize, I was approached by Jason Logan, a graphic designer and art director I knew from our years together at Maclean’s. “You have to introduce me to Margaret Atwood,” he said. “I have to give her something.”

“That’s funny, I was just talking to her this afternoon. But she’s not here.”

Then he blurted out: “I’m the voice of the Statue of Al Purdy on Twitter.” After that head-snapping coincidence, Logan’s statue tweets ended up in the Purdy film as little moments of Zen. But it didn’t stop there. What he’d wanted to give Atwood was a bottle of ink made from black walnuts harvested from a tree overlooking the statue.

Since leaving Maclean’s, Logan had found a new passion creating “living inks” with materials foraged from the wild — weeds, berries, flowers, rocks, rust . . . just about anything. And it all began with ink made with black walnuts from a tree overlooking the statue. I actually filmed Logan collecting them and cooking ink in his kitchen. That was a bridge too far for Purdy, and the scenes were cut. But they planted a seed, and some of the orphaned footage would find a home in my next film. I was filming The Colour of Ink years before I was even aware of it.

Footage begets footage. Logan later invited me to shoot some “ink tests” in his home studio, and that’s when I fell under the spell. As I watched an eyedropper squirt of ink come alive on a square of paper, it seemed to be moving and morphing with a mind of its own. A drop of lye, made with rainwater sifted through the ashes of a pear tree, would land in a pool of purple squeezed from buckthorn berries and produce a starburst of golden green. Viewing this through a macro lens was like stumbling across an undiscovered cosmos. And the desire to see that alchemy magnified on the big screen is what compelled me to make a movie.

Logan’s ink tests are his signature art works — stripped of ego by the notion that the ink is the artist. He began posting them on Instagram, where they found an avid following and caught the eye of a New York editor, which led to his 2018 book, Make Ink. Oddly, posting pixels on Instagram brought Logan back to the analog world of print — and to a growing community of kindred spirits who shared his passion for physical media and natural colour. He also posted his ink through mail, sending little bottles of colour to artists he admired around the world.

As a whim grew into a project, Logan and I agreed it would not be a typical portrait of the artist. His explorations would guide the narrative. But ink would act as our silent protagonist. We would follow his ink to find our story, tracing its path to a constellation of other artists. They ranged from Brooklyn’s Liana Finck, an irreverent young cartoonist making waves at the New Yorker, to Tokyo’s Koji Kakinuma, a calligrapher performing shodo brushstrokes on a monumental scale; from Corey Bulpitt, a Haida carver painting a cedar mask in British Columbia, to Roxx, a tattoo artist on an eternal search for “a blacker black” in the mountains above Malibu. And Margaret Atwood, doodling with a quill.

It wasn’t easy. I’d financed the Purdy film almost overnight, just by listing a pantheon of famous Canadian authors and singer-songwriters not yet cast. But it took me two years to get The Colour of Ink off the ground. I wrote countless pitches, which spun into synopses, outlines and storyboards. Shot in seven countries — Canada, the U.S., Mexico, Japan, Italy, Norway and the U.K. — it was an ambitious project. Eventually we found funding thanks to executive producer Ron Mann, who has mentored all my films into existence, and the National Film Board of Canada.

After making a biographical documentary about a dead poet, I wanted this one to work as visual poetry, without experts or talking heads. It would unfold as an odyssey tacking between epic and intimate landscapes, from Logan’s foraging adventures in the wild to the secret life of ink on the page. It would be a road movie, with a crew of just three guys in a van: Logan, myself and cinematographer Nick de Pencier, whose feats range from shooting The Tragically Hip’s final tour to framing eerily exquisite landscapes of industrial ruin in Watermark and Anthropocene, films he co-directed with Jennifer Baichwal and photographer Ed Burtynsky.

Ink is our oldest visual medium, and typically used to send a message, to leave a mark on some near or distant future. But Logan’s ink flows both ways: It carries a story of the place it comes from. Purple ink made from wild grapes picked along a rail path near his home in Toronto evokes memories of his mother, who died when he was nine. She introduced him to grapevines by the train tracks near their home in rural Ontario. The tracks scared him, but he saw the grapes as a kind of magic portal.

Logan’s search for the underworld of colour led us to unlikely places, from a Manhattan underpass where he scraped rust off a girder to a scorched California hillside where he made “wildfire ink” from charred bark. As we drove a van up the West Coast, it reminded me of my days in a band, happily riding a road to nowhere. But our journey was abruptly cut short by the pandemic. After flying home from a deserted airport in Seattle, we were stuck in Toronto for a year and a half.

Though we could no longer travel, Logan’s inks could. He airmailed them to artists to locations around the world, and I’d direct local camera crews remotely by Zoom from Toronto. Awkward, to say the least. But as the pandemic stretched our production schedule from six months to more than two years, it held a silver lining. Time deepens a documentary like nothing else. We discovered one of our most vital subjects, Japanese American painter Yuri Shimojo, a year after we were originally due to wrap. And as I cut and recut the film with editor Robert Kennedy, a master of the slow reveal, the story just kept opening up.

Logan and I are from generations two decades apart. His brain is still on fire; mine is tending the coals. We both slid from solid careers in publishing to land in a wilder place. He didn’t set out to be an ink maker; I didn’t plan to be a filmmaker. We fell down our respective rabbit holes, which met at the statue of a dead poet. Careers are weird.

Now that I’ve had some success making films, I inevitably get asked about my next one. But I’m not looking for a third act as a filmmaker. I’ve had enough careers. Like a lot of young writers who took jobs in journalism in the 1970s, I always felt that a career was a trap. The reason you became a writer in first place was to avoid it. In the late ’70s, I quit a newspaper job with a bridge-burning gesture, wrote a book of poetry, then spent a few years in a rock band. As a career, music was a dead end, but it changed my life and would come back to motivate my filmmaking. I created Al Purdy Was Here in tandem with an album of original songs inspired by his poetry. For The Colour of Ink, I worked closely with Don Kerr, our endlessly inventive composer, to find the sound of ink. Meanwhile, I drove our music budget into the red by licensing songs from k.d. lang, Bruce Cockburn, Leonard Cohen, the Pretenders — and recording an eight-piece ensemble that conjured the colour blue with music by Miles Davis, George Gershwin and Joni Mitchell.

After living that dream, I don’t need to make another movie. Each film began as a gift, became a self-made master class in how to do it, and was so much work I swore I’d never do it again. But the payoff — the showing your film to an audience — is like nothing else. It’s possible to distance yourself from it and feel proud of it in a way that you can’t with a piece of writing, because a film is not just your work. It stands there on the big screen, indisputably, like a building. You’re the architect, but it’s populated by a dozen other artists and was built by a team large enough to fill the theatre.

Now that I’m in the fourth quarter of my life, I plan to spend the rest of it slowing down. Spending more time with family and friends. Time with nature. Time “blackening pages,” as Leonard Cohen liked to say. If The Colour of Ink leaves any kind of message, it’s the need to stop, look around and just connect. I can do that by writing. Or picking up a camera and stopping time at 24 frames per second, but without a budget or a van. And I’ll try to look beyond the frame. As Iggy Pop once said, explaining why he no longer felt the need to make another album and turn everything into art: “Sometimes I just like a good sky.”

A version this article appeared in the April/May 2023 issue with the headline ‘Follow The Ink’, p. 48.

RELATED:

A Force of Nature: Marilyn Lightstone On Her Most Iconic Roles and Multifaceted Second Act

Basquiat: A Multidisciplinary Artist Who Denounced Violence Against African Americans

Second Acts: Canadian Entrepreneur Maggie Fox, 50, Shares Her Tips for Success