Ted Barris On Canada’s Heroic Dam Busters & Latest Book

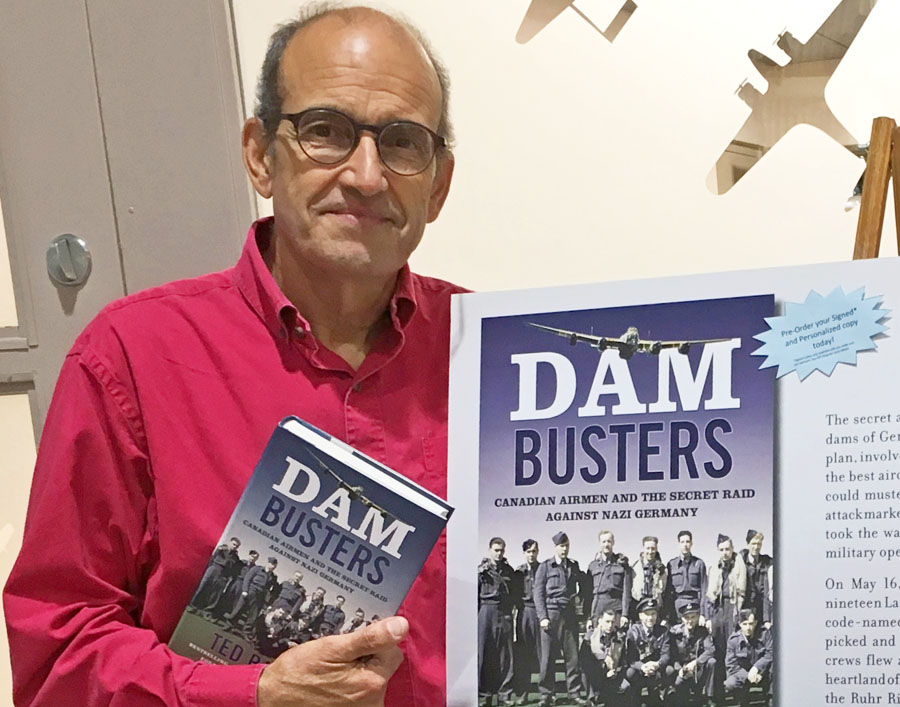

Photo courtesy of Ted Barris.

For more than five decades, journalist, author and broadcaster Ted Barris, 69, has dedicated himself to chronicling the oft-untold heroics of Canadian men and women in the theatre of war.

From shedding light on the Canuck contingent behind the famed Second World War POW prison break dubbed “The Great Escape” — popularized in the classic Hollywood film that ignores the Canadian effort — to the largely forgotten Canadian effort in Korea to the stories of the men and women who fought in Afghanistan, you’d be hard-pressed to find a conflict that the Barris hasn’t covered.

Seventeen bestselling non-fiction books later — not to mention a Veterans’ Affairs Commendation (2011), the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal (2012) and a Libris Best Non-Fiction Book Award (in 2014 for The Great Escape: A Canadian Story) — the Toronto native returns with his latest tome, Dam Busters: Canadian Airmen and the Secret Raid Against Nazi Germany.

The Dam Busters raid, as Barris explains, took place on May 16 and 17, 1943, after “a weirdo scientist in Britain named Barns Wallace invented a bomb that could bounce over the reservoir water where the Nazis had developed these huge dams on the Ruhr River.” He notes that the dams “powered the Nazi industrial military complex building the weapons that the Nazis were using against everybody in Europe. The scientists figured that if we could bomb those dams it would knock out all the water production, the hydroelectricity, the iron production and the steel production that was developing these weapons. And so the job of 19 crews was to fly in with a four engine Lancaster bomber at treetop level with a 10,000 pound bomb in its belly from England to the Ruhr Valley and back to deliver this bouncing bomb to those dams.”

Barris adds that, “This extraordinary operation … took place when the allies had no victories to their credit, [and] turned the tide to a certain extent in the war because this was a victory to breach those dams … water flooded for 100 miles down the river killing a lot of people but destroying those munitions plants and airfields and all the Nazi build-up for 100 miles. And nobody realizes this is a Canadian op.”

In addition to his work as an author and historian, Barris, in the interest of full disclosure, also taught journalism in Toronto for many years, where he served as my professor and mentor a decade ago. But now, in an interview setting, I put the questions to him, looking to find out what drives his passion for history and preserving these distinctly Canadian stories.

MIKE CRISOLAGO: I wanted to start by discussing the roots of your love for Canadian military history because I read that you wrote your first paper in elementary school on the War of 1812. That means you’ve technically been writing about military history since childhood.

TED BARRIS: It was actually a speech. When I went to school in the 1950s we had public speaking competitions. I chose a topic – I think it was the causes of the War of 1812 and it was probably Grade 7. I remember writing the speech because I dug into the history … and then stood up there and sweated bullets as I presented the causes of the War of 1812 to my classmates and the rest of assembly. For some reason I chose that topic and suddenly I realized that military stuff was visual, it was exciting, and if you could catch the stories of the people in the middle of this stuff, so much the better.

MC: Did you win the speech competition?

TB: I don’t think I did, no. I think probably somebody who picked a topic that the teacher liked more than the War of 1812 did. [He laughs] But it was a great experience and the one redeeming thing about that, now that I’m thinking about it, is the man who was my teacher then, Mike Malott … kindled my love of history. He realized that I had a penchant for it and a fascination of it and he instilled that in me … We had a history class scheduled [one] afternoon and we came back in the classroom and we’re sitting there [and] where’s the teacher? Chaos is beginning to break out in the room and no one’s paying any attention [and] all of a sudden the door bangs open and Mike comes in with a three corner cap, boots up to his knees, a cape and a ruler as a sword and he leaps up onto the desk and he becomes Vasco da Gama, the great explorer of the Pacific, and we were kind of like “Holy smoke who is this guy?” But in an instant he grabbed our attention … Mike instilled that passion from that day and unfortunately he’s gone now but I did have an opportunity in one of my books, Days of Victory back in 2005, to dedicate the book to him and a thank [him] for the gift of his passion for history.

MC: You’ve written 17 non-fiction bestsellers and often they’re Canadian military tales that are overlooked or forgotten by history. What is your process for finding a topic and then deciding to write a book about it?

TB: There are a number of criteria that I choose to run across the grid of what I’ll do next and why. Very often it’s anniversaries. I wrote The Great Escape book coming into the 70th anniversary of The Great Escape in 1944. I wrote a book about the Canadians landing on Juno Beach called Juno in Normandy also in 1944 – I wrote that in 2004. So the anniversary aspect is very much a part of the decision-making process. I’ve been blessed to have had an opportunity to meet probably between 5,500 and 6,500 veterans over the years that I’ve done all this, which means that between 5,500 and 6,500 people opened themselves up to me to reveal some of the toughest experiences of their lives. Probably the most revealing of which were some of the men I met in the preparation of Breaking the Silence who had come back from Afghanistan. The reason for that was that the veterans from Afghanistan had not had 50 or 60 or 70 years to get it into their system, to work out the words they would describe it and to deal with the feelings clearly very traumatic. That’s why we call it Post Traumatic Stress.

MC: So when you settle on a topic, like, say, your latest book, Dam Busters, what’s the process for putting the idea to the page?

TB: You’ve got to try to find out if the resources are there, if the raw material is there. I had the good fortune to stumble across Canada’s last surviving Dam Buster, a man who participated in the raid. Fred Sutherland was a front gunner on one of those 19 Lancaster’s flying from England to Germany and back, so he had a front row seat literally to what had happened when they fly in to bomb the damns. I found that Fred was alive and well and living in Alberta. I thought, “I’m going to see whether this guy has got a story” and I went there and I sat with him for three days. His wife was suffering horribly from cancer and so he was distracted somewhat by coping with her medical needs, but he sat down with me and I quizzed him from the start of his career as an aviator right through [his experience in the war]. The minute he comes home he marries his sweetheart and leaves all that behind. That’s the story I got from Fred and I realized I got something, so what I had to try to find out was where were all the other Canadians? There were 133 men on those 19 Lancasters flying to Germany to do the operation. A quarter of them were Canadians and nobody knows this.

MC: In fact, you wrote in your book that there have been so many other books and films about this Dam Busters operation but that, “You can’t find the Canadians in any of them.”

TB: And they’re everywhere — there were Canadian pilots in this rig, Canadian navigators, flight engineers, bomb aimers, gunners, ground crew Canadians. In addition to the men on the operation one of my thesis in the book is the [fact] that most of these guys [who] were trained here in Canada, even the Brits, made this operation possible. All of the training of air crew, bomber crews, fighter crews, ground crews, transport crews, coastal command, everybody was trained in Canada. We trained a quarter of a million men here in the Second World War for military air operations and half of the men on the Dam Busters raid were trained in Canada, which means if they hadn’t had that basic high standard of training here, none of this could have happened. So it’s a Canadian story from its roots to its treetops.

MC: So after all this work you put in on all your books, why, in your mind, is it important that these Canadian stories are told?

TB: Very much for the reason that we’ve been discussing. Canadians are not considered warriors. Since the time I went to school in the 50s and 60s, only our peacekeeping operations, at best, were discussed. We’ve never been described as a warrior nation when nothing could be further from the truth. We have been part of the World War operations in South Africa, the First World War, the Second World War, the Korean War, the NATO operations, Afghanistan, Iraq, on and on and on and on. We have a warrior tradition. I’m not suggesting that that’s good. I am a pacifist. I’ve never had my hands on a gun – I have no interest in them, nor in violence. But to find the stories of these men and women who were ordinary and went through extraordinary things to me is so powerful, so attractive, and a lot of people ignore that, thinking, “Ah that’s old war stuff, why would we be interested in celebrating or acknowledging that?” Well, because we played a role in restoring peace to Europe twice, because we played a role in trying to restore peace in the Korean peninsula and get women who have never had a chance to go to school in Afghanistan that chance. All of those reasons, for whatever the politics, put men and women from Canada in extraordinarily sensitive and difficult positions. Why not find out what that was like? That’s part of it. And my dad [journalist and author Alex Barris] is part of the story. He was a medic in the American Army so the next book I’m working on will explore what medical personnel experienced. So the human experience in warfare is something that will probably be analyzed long after I’m gone, but if I can begin to deal with it in a very tangible [way] while the veterans are with us still and even if they’re not, maybe I’m contributing to a better understanding of what that’s like, why it’s wrong to wage war, why it’s sometimes necessary and how young men and women, who bare the brunt of this experience, fare and how it changes them.

MC: Not to close out our talk on an overly existential or philosophical note, but you’ve interviewed thousands of veterans who’ve face unimaginable horrors and pain and death. What has learning about the worst and, in some cases, the best of humanity taught you about the human experience?

TB: The human condition among Canadians who’ve served in these operations and others is one of extraordinary selflessness. These men and women put their lives on hold knowing very little about what they were getting into but sensing that it was important … and did that somewhat in the naïve faith that they would survive while others wouldn’t and come home untouched, unscarred, unchanged and go back to their lives. And many of them did. One of my dearest, oldest friends, Charlie Fox, was a Spitfire pilot. He was [originally] a shoe salesman. He trained air crew for two years, he went overseas, he did 232 Spitfire sorties, got two distinguished flying crosses [and] would have been quite content to keep fighting during the war. But they recognized he’d done his full tour [and] said, “Charlie we’re going to send you home by way of Buckingham Palace to receive your DFC’s, but you’re done.” And he said, “I’m not going to Buckingham Palace. If you don’t want me to fly anymore I’m going right home because I have a wife and a son and a job I want to go back to and remember what civilian life was like.” And he forgot about it and put his entire wartime history in the closet until Ted Barris comes knocking 50 years later and says, “I hear you were an instructor and you flew Spitfire?” And away we went and he became like a dad to me because they did [a lot] but were not the American or the British veteran who spent a lot of time waving a flag, busting their buttons with pride and bragging to a certain extent. Canadians aren’t like that, and that’s another part of the human condition among warriors that’s worth exploring.

Dam Busters: Canadian Airmen and the Secret Raid Against Nazi Germany is available in stores and online now.