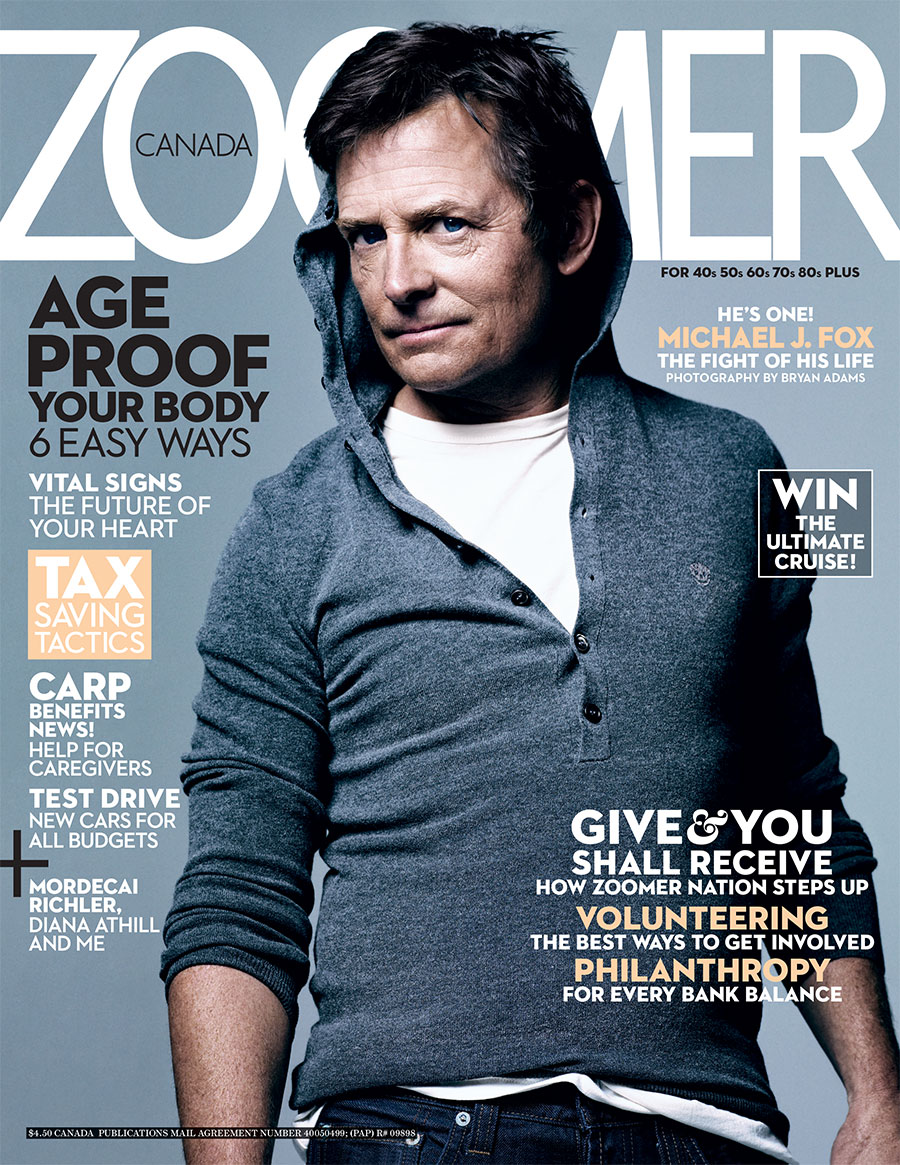

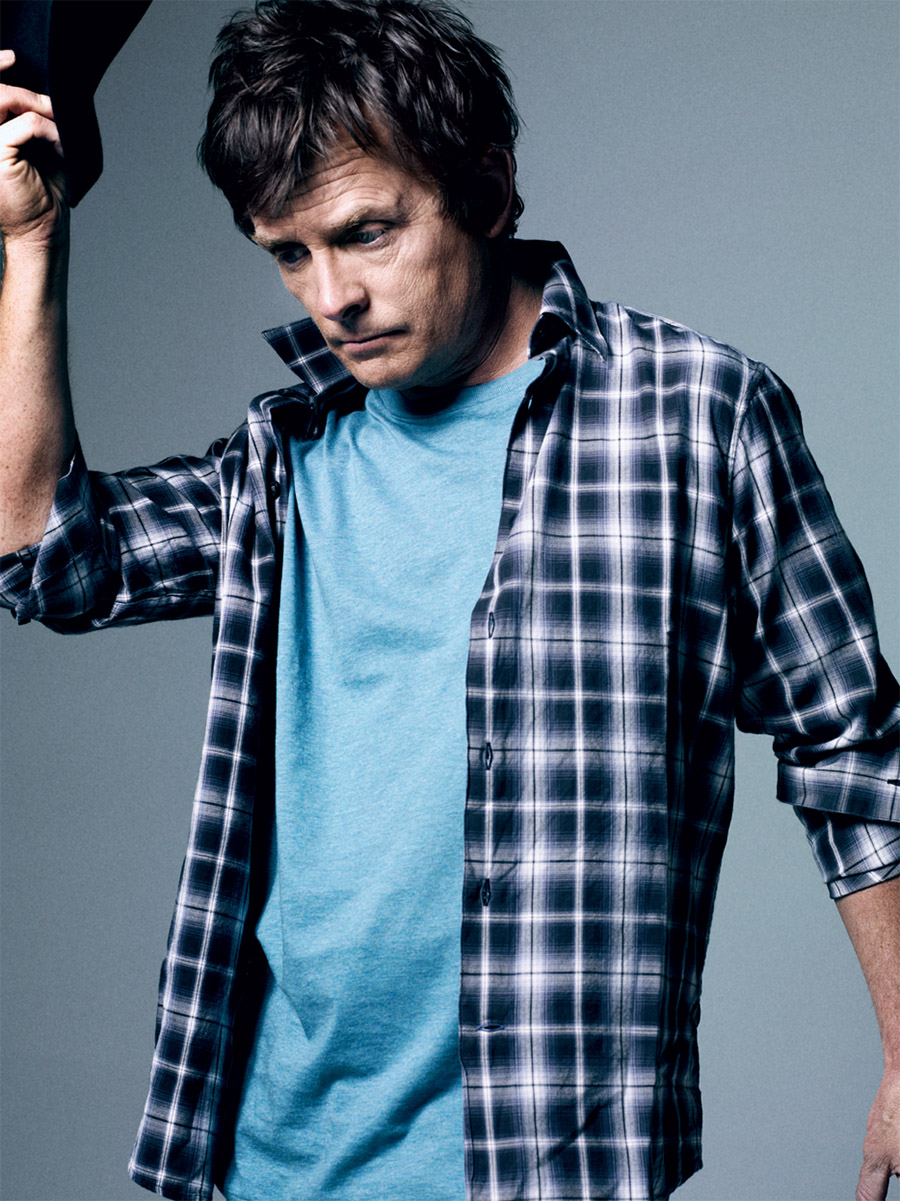

My Way: Michael J. Fox Brings His Own Brand of Activism to Canada to Continue the Fight Against Parkinson’s Disease

Michael J. Fox retired from acting in 2020 and said he planned to devote himself to helping find a cure for Parkinson’s disease. Photo: Bryan Adams

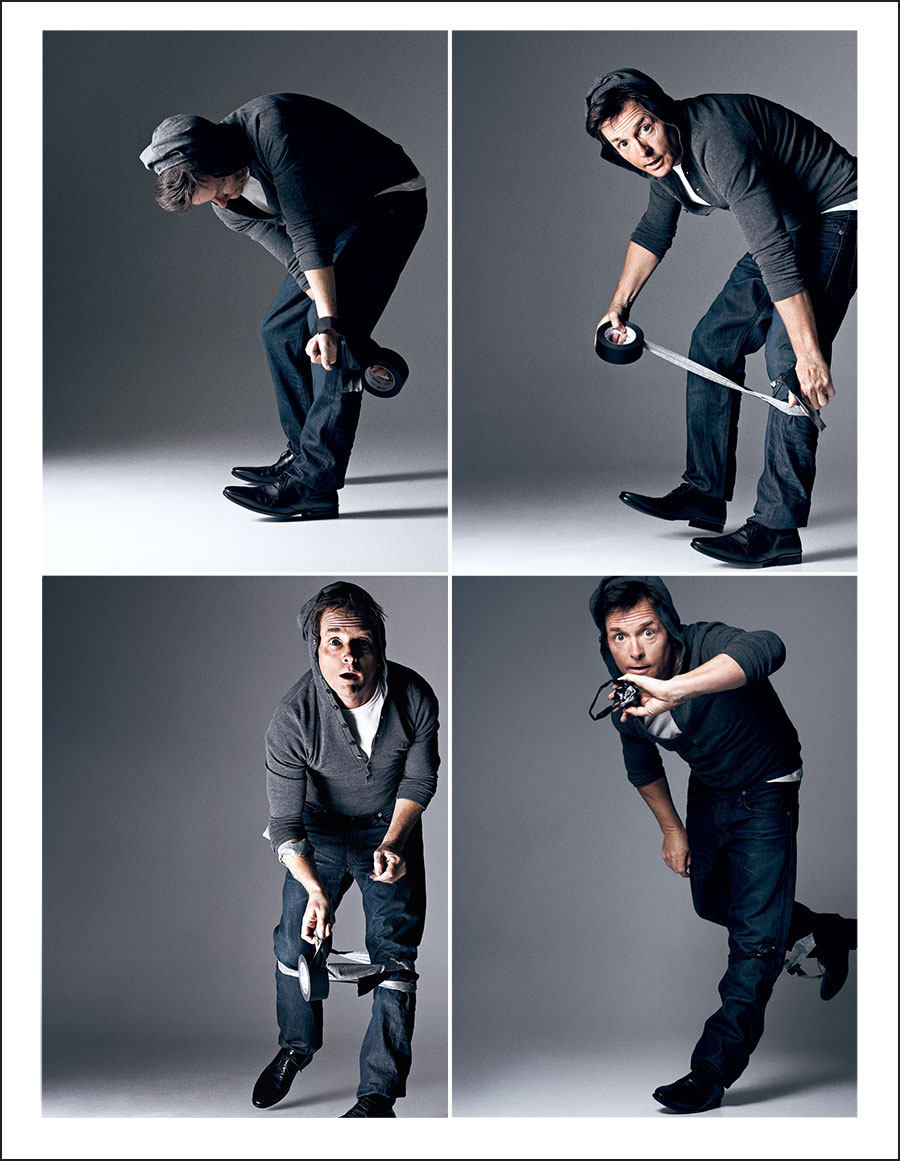

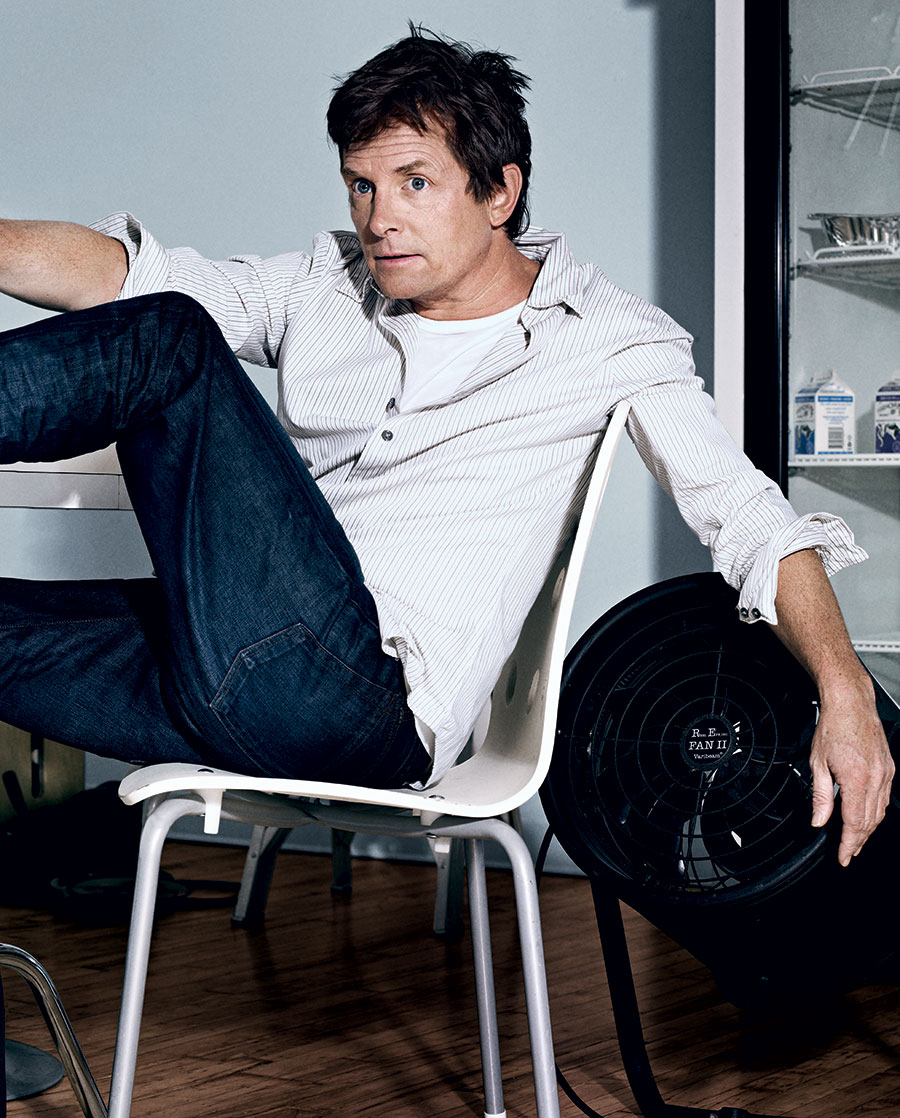

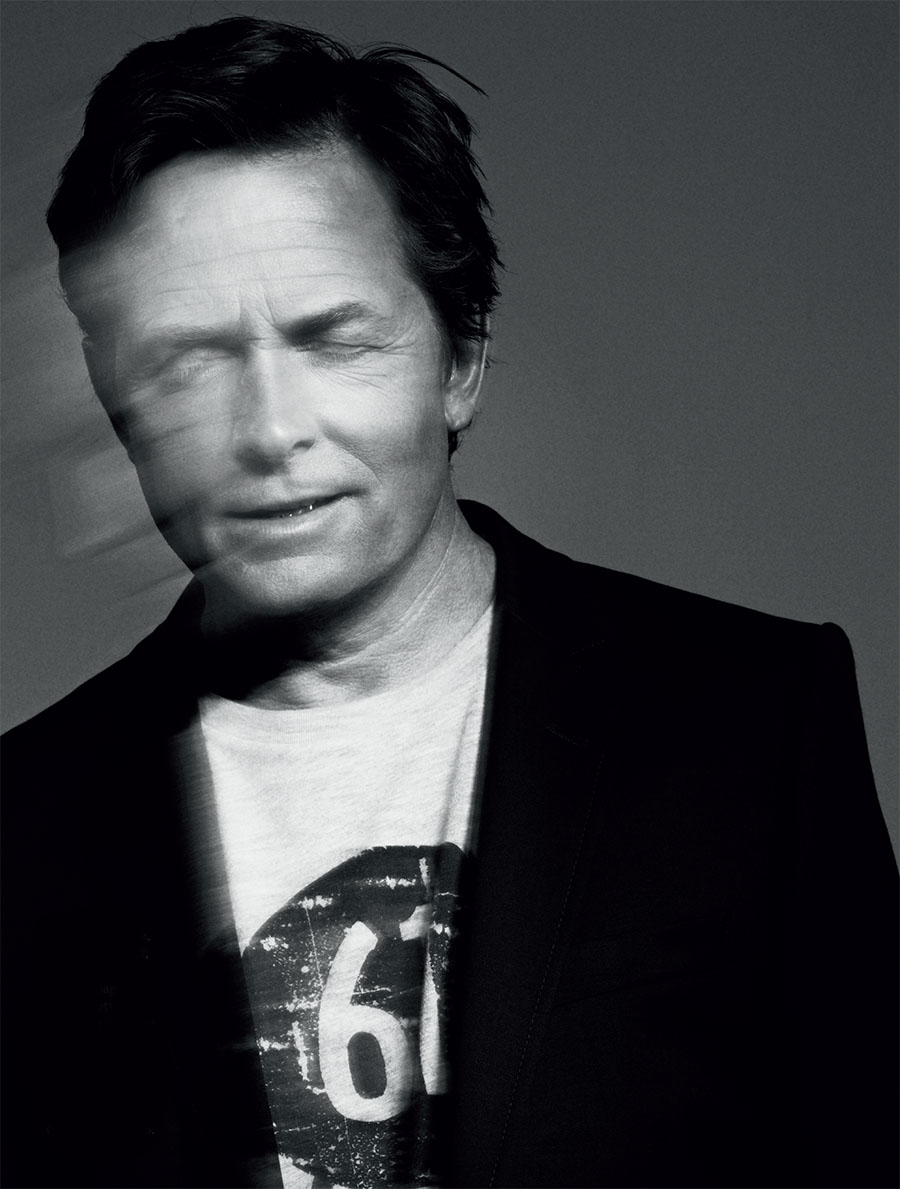

Some part of him is always moving, but it’s not distracting, not significantly. As Michael J. Fox chats away this December morning on the slouchy sofa in his Manhattan office, he sometimes uses one or both arms to gesticulate, and sometimes his knees jiggle like an overcaffeinated kid’s. He pushes up the sleeves of his grey V-neck sweater, then tugs them back down. He readjusts the brim of his baseball cap, crosses and uncrosses his jean-clad legs, fiddles with the tops of his gray ribbed socks. (He never messes with his loafers, though; later, you’ll learn that snug shoes help keep his feet working.) He doesn’t seem troubled or in trouble. In fact, he seems like any other fidgety actor—they’re a jittery bunch.

But pretty soon you notice that the fabric on one sofa arm is nearly worn away (his usual spot?). And despite his animated, articulate answers—Fox has always known his way around an anecdote —his voice sounds thin and strained, and his words occasionally slush together. You realize that all his readjustments are tricks to disguise the involuntary movements of Parkinson’s disease (PD), which he’s lived with for 18 years. He’s only 48. Today is one of his good days.

PD, a neurological disorder that destroys dopamine, a brain chemical that controls motor functions, usually strikes people much older than Fox. (There are six to seven million sufferers worldwide.) As diseases go, it’s a bitch. Without enough medication, the body shuts down — the face freezes, muscles and organs stop working. With too much, dyskinesia, a violent sideways swaying, sets in. (Fox was experiencing dyskinesia when he recorded the political TV ad that right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh accused him of exaggerating his symptoms in; more on that later.) For a PD sufferer, every day—every hour—is a crap shoot: sometimes the medicine prevails, sometimes the disease, and there’s no predicting which. Some days, Fox can only pace, tracing circles around one piece of furniture and then another for 20 minutes at a time, unable to gather his thoughts or control his voice enough to speak coherently. “It’s like being shaken,” he says. Most horrifyingly, PD is degenerative: over time, symptoms worsen and the effectiveness of medication wanes.

But Fox would be the last person to want you to feel sorry for him—or in his feistier moments, to give a damn if you do. He left his vanity and self-pity behind years ago, along with a bad booze habit. Enough teenage girls had hung his pretty picture on their walls, he’s fond of saying. He lived his Hollywood dream: Edmonton kid moves to L.A. at 18, adds a cool-sounding middle initial to his white-bread name and climbs to stardom in two hit series, three Back to the Future blockbusters and a score of other films. I first met him on the Florida set of the 1991 comedy Doc Hollywood, where he roared around in a rented Corvette and hung out in a movie trailer stacked with cases of Diet Pepsi, whose ad campaign he was headlining. He was living in his hotel’s presidential suite and closing down its bar every night. One finger had just started to twitch. His PD would be diagnosed in a few months.

Some of Fox’s choices: Don’t think in terms of “last times.” Don’t worry in advance: “Tracy (actress Tracy Pollan, Fox’s wife of 21 years) can be a hypochondriac,” he says. “I always say to her if you obsess over your worst-case scenario, probably you do it for nothing, and if it does come to pass, you’ve done it twice.” Be frank: Fox doesn’t hesitate to answer questions about whether he can pee straight (a daily struggle) or have sex. “Sex is not a problem,” he says. “There are times when you are the agent of motion and times when you’re not. For me, it’s great. It’s like my mother once said, ‘The secret to a long marriage is to keep the fights clean and the sex dirty.’ ”

One more choice: Don’t engage with idiots. During the 2006 U.S. midterm elections, Fox recorded TV ads for candidates (usually Democrats but not exclusively) who supported stem-cell research, which the Bush administration had forbidden any institution that accepted federal aid—i.e., nearly every university and research hospital in the U.S.—to do. (One of the Obama’s first acts was to overturn the ban.) While taping his ad for Missouri Democratic Senate candidate Claire McCaskill, Fox was particularly dyskinetic. Rush Limbaugh on his radio/TV show accused Fox of faking his symptoms, egregiously aping Fox’s movements.

But Limbaugh failed to understand the goodwill Fox had built up over his lifetime—not just with his characters but in the grace with which he’s handled his disease. Fox received a startling amount of personal and media support, which only increased when he steadfastly refused to bite back. “It reminded me of when I was a kid,” Fox says now. “Because I grew up small (he’s five feet four inches), I had to deal with assholes like that my whole life. He was so preposterous, and so to the script. It was like professional wrestling. But I refused to jump off the rope and hit him with a folding chair. I knew that he was wrong. Not about stem cells—anybody can have any opinion about that. He was wrong in the way he did it. It was a shortcut, just bullying. Just lazy.”

Still, I ask, didn’t it make you furious? “I felt exhausted a couple of times,” Fox says. “Tracy congratulated me, though. She was happy to see me not care if I pissed somebody off. I like to be the good guy getting along. But this time I truly didn’t care if I pissed them off because what are they going to take from me? Are they going to come and kick my dog? The combination of Parkinson’s and all the great things that happen in my life put it into relief.” The gift of perspective, I say. “Yeah,” Fox shoots back, “the gift that keeps on taking.”

It’s those little snipes that keep Fox interesting. He’s not allowed becoming the public face of a terrible disease to turn him into a martyr. “I know I’m tougher than a shit-house rat,” he says, enumerating a family history—his grandfather, who lost an eye in the First World War; his uncles who were prisoners of war in Germany; his father, who was in the Army for 25 years—that makes him conclude, “If this [PD] is my fight, this is nothing.”

So when his twins squabble over a sweater, Fox will roll his eyes like any father, but he’ll also take an extra beat and think, “Maybe it’s about who the alpha dog is that day.” With people like Limbaugh, “I don’t go, ‘Fuck you!’ ” Fox says. “I go, ‘Really? Is that what we’re doing? Okay …’ ” Instead of being furious that Parkinson’s brought his career to a screeching halt, Fox realizes that it made him quit drinking and gave him time to really get to know his kids, about whom he talks with evident delight.

“It really is about choices,” he finally says. “I don’t have a choice whether I have Parkinson’s, so why spend one second on that? But I have a choice about how I feel about everything else.”

His foundation—the second-largest funder of PD research after the U.S. government—mirrors its founder’s practicality. Over the last 10 years, it’s become a model in fundraising because it applies the tenets of business to philanthropy: every donation that comes in goes straight out in grants. All good ideas are funded, regardless of country or institution. If a line of research hits a wall, money is diverted elsewhere. Grantees are expected to share information with one another and to actively pursue practical applications—both rare in conventional research. Drug companies are not the enemy: one of the MJFF’s greatest success stories was a $1 million grant to Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, which led to results promising enough that the company itself invested another $10 million to keep it going.

Fox knows PD will close in one day and that he’s going to die—but, he says, who isn’t? He’s been through “that whole Elizabeth Kubler-Ross five stages of death thing” and he’s made the choice to not live in bitterness. “It really comes down to, for me, if I do the right things on a daily basis, tomorrow will take care of itself,” he says. “I look in my kids’ eyes—and I would see it if it was there —but I don’t see fear. They feel secure and know who I am in their world. I can’t anticipate some calamity and I don’t want to. It’s why I don’t take pictures on vacation because if I go like this [he makes a clicking-camera gesture], then I’m not on vacation anymore. I’m in this box. So maybe I don’t have as many pictures. But I have more memories.

A version of this article appeared in the March 2010 issue.

RELATED:

Michael J. Fox and Martin Short Headline Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards