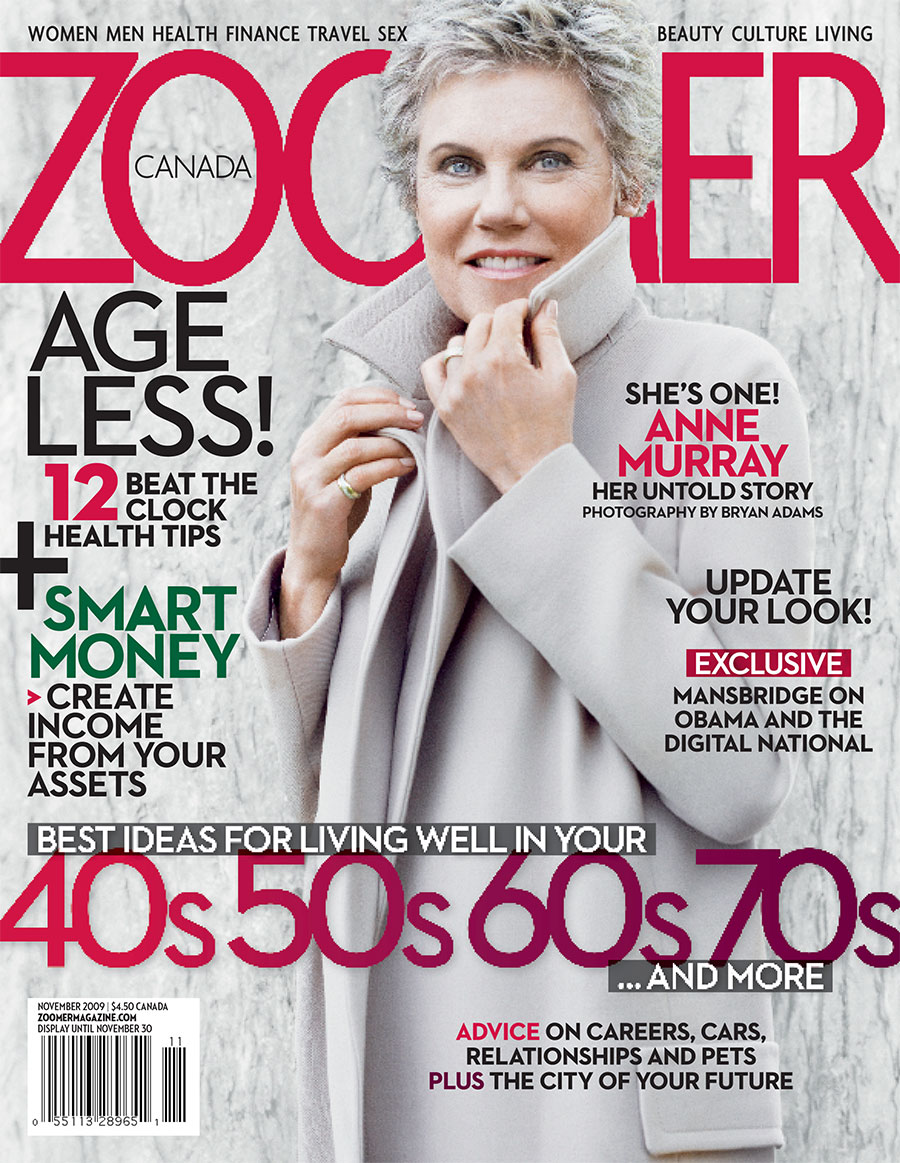

‘All of Me’: Anne Murray On Her Autobiography and Her Decision to Retire From Music

Photo: Bryan Adams

With the publication of her autobiography, All of Me, iconic songstress Anne Murray sets the record straight.

When one of the most identifiable and beautiful voices in the history of recorded music announces that from now on she’ll be singing only among family and friends and perhaps in the shower, it comes as sad news.

In the final chapter of All of Me, an auto-biography being published this month by Knopf Canada, Anne Murray makes it quite clear that she thinks the time has come to hang up her skates. Even delivered with the bravado of jock metaphor, her decision leaves this sook feeling blue.

Sure, a literary debut at the age of 64 is a happy affair. Co-written with veteran journalist Michael Posner, the book, coming out in both Canada and the U.S., is being treated to a print run of Atwood proportions and supported by a 14-city promotional tour that will take Murray to Moncton for a signing at Wal-Mart and to Toronto for an appearance at the International Festival of Authors.

But to think that she’s giving up song, that hurts. The pang gets worse when I talk to her on the phone. She’s at her summer place in Nova Scotia, on the Northumberland Strait, from where at night she can see the lights of Charlottetown. There can’t be all that many, I joke to myself, trying to hang tough, but mere mention of them is enough to put this Cape Breton-born Maritimer in a maudlin mood. And when she starts talking about not singing any more, it makes me misty.

I have to ask, “What does it do to you?”

“Oh, nothing,” Murray says, and laughs, leaving me unsure of what was so absurd, the question or the answer.

The funny part, of course, is that I couldn’t tell. Although in 1981, I wrote Anne Murray: The Story So Far, a paperback biography that is probably the definitive work on her kitchen reno, and I did the liner notes for Anne Murray: Now & Forever, a boxed set of three cassettes that was released in 1994, I still find Murray to be strangely elusive.

Making no big deal of it, Murray explains her retirement with a club-woman’s propriety combined with a Mother Superior’s strictness.

“This is something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. It’s hard but, you know what, I know it’s the right thing to do. Because I can still sing and I think that’s the time to stop, when you can still do it. Otherwise, you end up with people feeling sorry for you. There are many of my peers who are shadows of their former selves. I see it and I think it’s unfortunate,” she says, chasing her pious opinion with a hearty shot of self-regard: “Maybe I set the bar too high for myself. It’s hard to settle for less.”

There is no fake modesty in All of Me either. Murray acknowledges that she became a “meta-entity” and does her best to analyze what has made her such an iconic figure.

Career alone doesn’t account for it, even one that began 40 years ago with the television hootenanny out of Halifax called Singalong Jubilee, and that grew to include hit singles, guest spots on American television, gigs as a headliner in Vegas, successes on both country and pop charts, critical acclaim from Elvis Presley, John Lennon and Rosemary Clooney, countless awards, almost as many hairdos and an honorary Canadian postage stamp.

However, Murray’s rise to symbolic status also had something to do with her character. An enigmatic blend of candour and restraint, she has charmed audiences with shamelessly rehearsed patter, all the while insisting that she was never cut out to be a public performer. It’s a riddle that she herself doesn’t solve. At the end of All of Me, all she says she is is, “Just a girl from Springhill, Nova Scotia.” That would sound disingenuous had Murray not done such a thorough job of redefining what “just a girl from Springhill” means. She was never just the “straight, clean and simple” — the title of her 1971 album — young woman who appeared on stage in her bare feet. In fact, as her book reveals, she’s more complex than she’s given credit for.

Some cats knew that all along. In 1973, reviewing an album for Creem magazine, the legendary rock writer Lester Bangs dug beneath the obvious for a theory that ascribed Murray’s “hypnotically compelling” appeal to “the scientific application of that time-honoured and almost forgotten erotic technique — the holdout.”

In All of Me, Murray owns up to some of the delaying tactics she’s resorted to. To get out of her first recording contract she told them she wanted to extend her three-year deal to five. They fell for it. She asked them to return all copies of the original agreement, burned them and signed on with Capitol, an international giant.

On the romantic front, Murray also engaged in subterfuge. In 1975, she married Bill Langstroth, who had been her producer and manager and who at the start of their relationship in the late ’60s was still living with his first wife. “[W]hen reporters asked about my love life, I said I was too busy to have one,” she now admits.

In the paragraph before that, she mentions that it was around that time that Brian Mulroney sought to court her. At least once when he came to her apartment, Murray had her roommate tell him she was not at home.

Although she confesses her own transgressions, Murray says, “I have gone out of my way not to say bad things about people.” There are a few recollections that could be considered catty. She describes a backstage visit from a bellowing Robert Goulet, a singer who, before Murray, was one of very few Canadian stars to make any noise in the States. As for Céline Dion, one of the many who came after, it sounds as if Murray is still smarting from a post-show visit to Dion where instead of being shown to a private holding area, Murray waited for an hour in a crowded room. “I couldn’t really blame Céline — she very likely had no idea this was happening — but her handlers ought to have known better,” writes Murray rather stonily, a stern diva with etiquette on her side.

There’s even a lurid scene that Murray looks back on forgivingly as “drunken foolishness” but reads like something out of Jackie Collins, when Dusty Springfield, a singer Murray idolizes, came on to her, pretending she needed help in the washroom with a broken zipper.

But the book doesn’t deal in tattle nor aim to settle scores. It doesn’t have to. One decade alone — the 1990s — provided Murray with enough drama for any memoir. It was 10 years jammed with professional trials and personal tribulation. She was dropped by Capitol Records, divorced and dealt publicly with her daughter Dawn’s anorexia.

Not the least bit the tell-all type, in preparing All of Me, Murray extended veto privileges to Dawn, 30, who put out her first full-length album, Highwire, last month; and to her son William, 33, who is studying Greek and Latin at university, wants nothing to do with show business and who has told his mother that she is doing the right thing, “quitting before you suck.” Murray also consulted with her ex-husband Bill Langstroth, who remarried nine years ago and with former members of her band to make sure that she wasn’t violating anybody’s privacy.

A stickler for discretion, who has sometimes pushed it to the brink of disguise, Murray is also wise enough to recognize that it’s not an entertainer’s job to be introverted. Indeed, she does some of her hardest work trying to be outgoing. Autobiography didn’t come easy. “There’s a lot of stuff I would prefer not to say. Period. But that’s what this was about. That’s why I had a terrible time with this book.”

Nothing was more difficult than coming to terms with the death of Leonard Rambeau who, at 49, died of colon cancer in 1995 (Murray has since become a spokesperson for Colon Cancer Canada). A canny Nova Scotian and, also like herself, something of a control freak — “It was a contest. Definitely,” Murray concedes — Rambeau joined Murray’s team in 1971. He was the L in Balmur Limited, the company they founded to handle her whirlwind celebrity. As president, he nurtured her image with tireless vigilance and attention to detail.

Big on retouching, he was also a big spender whose lavish vision took a toll on the infrastructure. After he died, Balmur turned into a runaway train. It was sold in 2001. “I was glad to see the end of it,” Murray writes. “I had lost millions.”

Other inestimable losses were to come. In 2004, Cynthia McReynolds, Murray’s golfing buddy, was taken by cancer. And, in 2006, Marion Murray, Anne’s mother and sparring partner was laid to rest.

In All of Me, Marion Murray is remembered as “a great, smart, loving woman I was blessed to call Mom.” Née Burke in 1913, she was of Acadian stock that goes back to the 17th century and a woman who held herself to a level of chic, domestic arts and social conduct.

As I said before, I have Murray memories of my own, and none are fonder than those of Marion Murray meeting me at the bus station when I arrived in Springhill to do research among her proud stash of scrapbooks. She would have me stay nowhere but in her home, served fresh brown bread and impressed me with her spry attire. It was Marion Murray’s brother, the oddball Uncle Harry who played piano for silent movies whom Anne Murray said I reminded her of the first time we met.

There was also eccentricity in Murray’s paternal legacy. Dr. James Carson Murray, her father, served his community with diligence and compassion but shunned the limelight and took all his meals in bed. Murray takes after him in her reclusive instinct that has sometimes made her forays into glamour seem insincere in the same way that her natural-born irreverence sometimes turned into stagey sass.

Nevertheless, there’s always been something real about Murray’s reluctance — that holdout thing again. In 2007, she flatly refused to do another album. Her manager, Bruce Allen, had to coax. Murray recanted. The result was Duets: Friends & Legends, a disc that was her most popular in years. It resurrected her profile to the point that she could take advantage of it by writing this book. It also paraded her skill at singing harmony, one of her greatest gifts, and paired her with other female vocalists, among them, Dion, Shania Twain, Nelly Furtado and k.d. lang, all of whom were beneficiaries of Murray’s ground-breaking example.

“When I started in this business, people were going, ‘Oh well, she’s Canadian. She can’t be that good.’ Of course, we are,” says Murray, repeating what she told the audience in September when she hosted the ceremony honouring the latest inductees into Canada’s Walk of Fame.

Currently, Murray is perfectly content with official retirement. “I’ll take it as it comes, I guess,” she says, sounding enviably relaxed, self-accepting and relieved of the pressure to be constantly on. That’s the bad news. The good news is that her voice, now lower, is still good. She’s as willful as she was as a child fighting with her mother over curls and dresses. And, best of all, the contradiction that resides inside her and makes her fascinating could burst forth again.

Retirement “feels like what I want to do but, in a year’s time, I could say, ‘Oh, my god.’ ” We are left to hope that she does.

A version of this article appeared in the Nov. 2009 issue.

RELATED:

Buffy Sainte-Marie: Tracing the Indigenous Icon’s Impact as an Artist and Activist