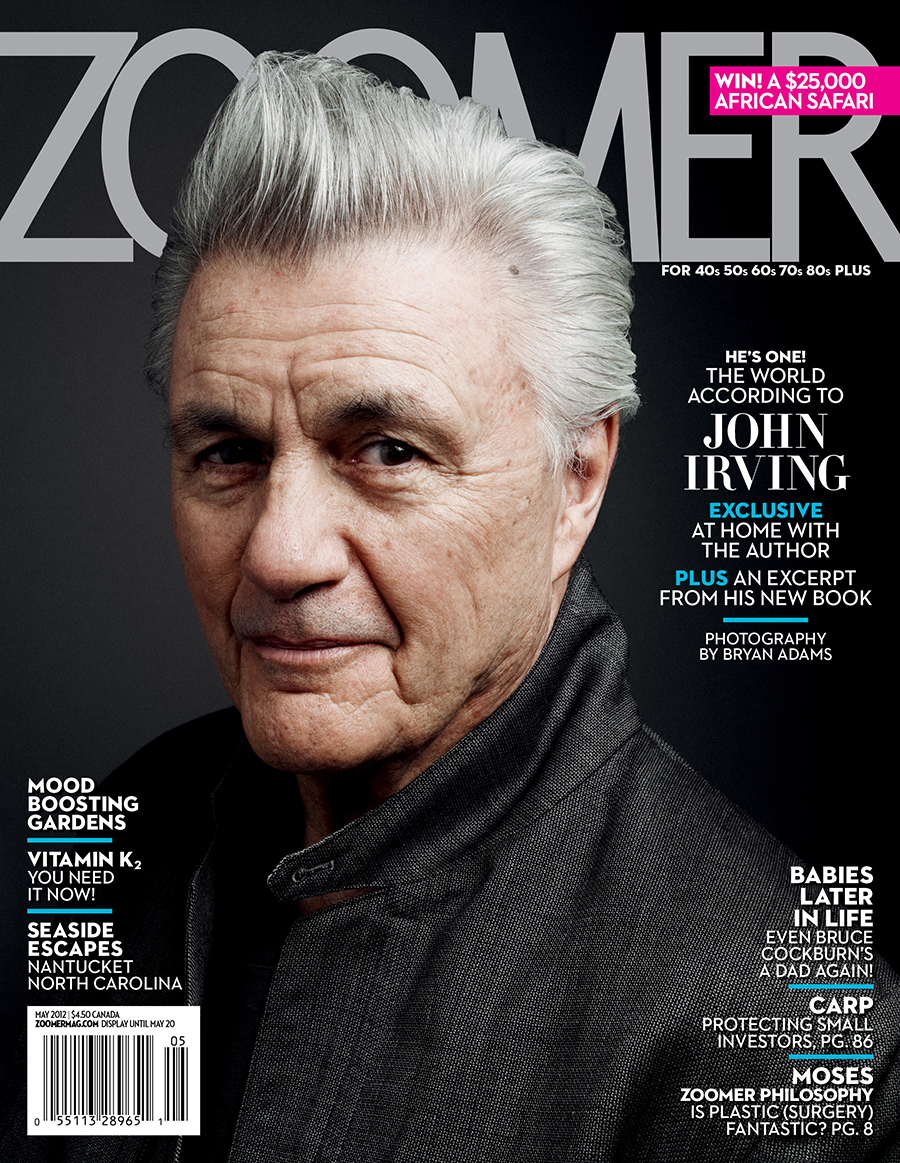

Literary Legend John Irving On His “Wrestler Mindset” and Why Fear is Always at the Centre of His Novels

Photo: Bryan Adams

So this is what the top of the heap looks like: a sprawling home high on Green Peak in Manchester, Vt. A sun-drenched office with a wall of windows offering a view all the way to Massachusetts. Framed awards crowding the walls, including three New York Times bestseller lists blown up to poster size, from the weeks that the novels The Fourth Hand, A Widow for One Year and The Cider House Rules were No. 1. A best adapted screenplay Oscar on a bookshelf. One arm of an L-shaped desk, piled with tidy stacks of manuscript pages and old-school reference texts, serves as a topographical to-do list. The other arm is where John Irving writes, in longhand, the books that got him here.

In an era of slice-of-life fiction, Irving’s novels are smorgasbords, generously peopled, militantly humane, groaning with lust, absence, accident and the passage of time.

“My grandmother died a few days short of her 100th birthday, and [near the end] her only memories were the ones that made her laugh or cry,” Irving says over coffee on a diamond-bright January morning. “She would be laughing, telling a story, and suddenly her face would darken because half the people in it were dead. I thought, ‘This is it. This is what you do: you think of the funniest fucking thing you can think of and then you turn it on a dime until it’s not funny at all.’”

Clearly, his method works. His first 12 books – from 1968’s Setting Free the Bears through his breakthrough, 1980s The World According to Garp, and beyond – have been translated into 35 languages, include nine international bestsellers and were made into five films. (He wrote the script for The Cider House Rules himself, and both he and its star, Michael Caine, won Oscars.) Novel No. 13, In One Person, drops this month, and it could cause a ruckus, given its timing – a U.S. presidential election year in which gay marriage is a hot topic – and its subject matter: it explores gender issues as fiercely and forthrightly as Garp tackled sexual politics and Cider House took on abortion.

“I wasn’t afraid of anything until I had a kid,” Irving says. “Then I was terrified because immediately I could imagine a hundred ways in which I could not protect him. But I also got my subject: what are you afraid of? The subject is always what are you afraid of. I don’t begin a novel unless there’s something about it that makes me say, ‘God, please don’t let this happen to me.’ ”

The new novel is merely one milestone that Irving will hit this year. He turned 70 on March 2, with a birthday bash in New York City. In June, he and his second wife, the Canadian literary agent Janet Turnbull, will celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary. 2012 also marks the fifth year that Irving has been cancer-free, after a successful prostatectomy in 2007. Sitting at the long wooden table in his bright, open-concept dining room, surrounded by scores of family photos – including his three sons and four grandchildren – you have to wonder: how did a guy who spends his days spinning worst-case scenarios end up with such a contented life?

You can say this about Irving, he’s a model of discipline. He rises early, savouring the time before anyone else is awake. “I don’t think you dream of becoming a novelist unless you first know that you need to be alone,” he says. “The part of your day that is most essential to you is the part when you’re by yourself.”

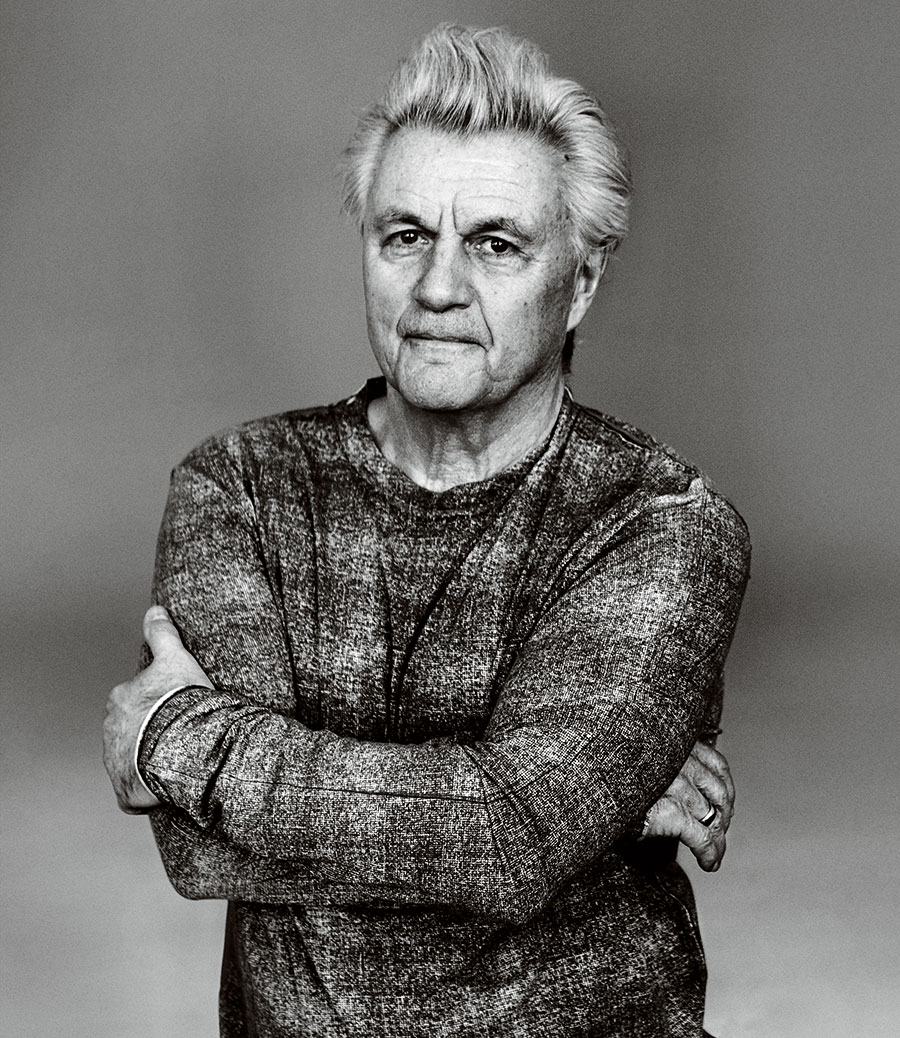

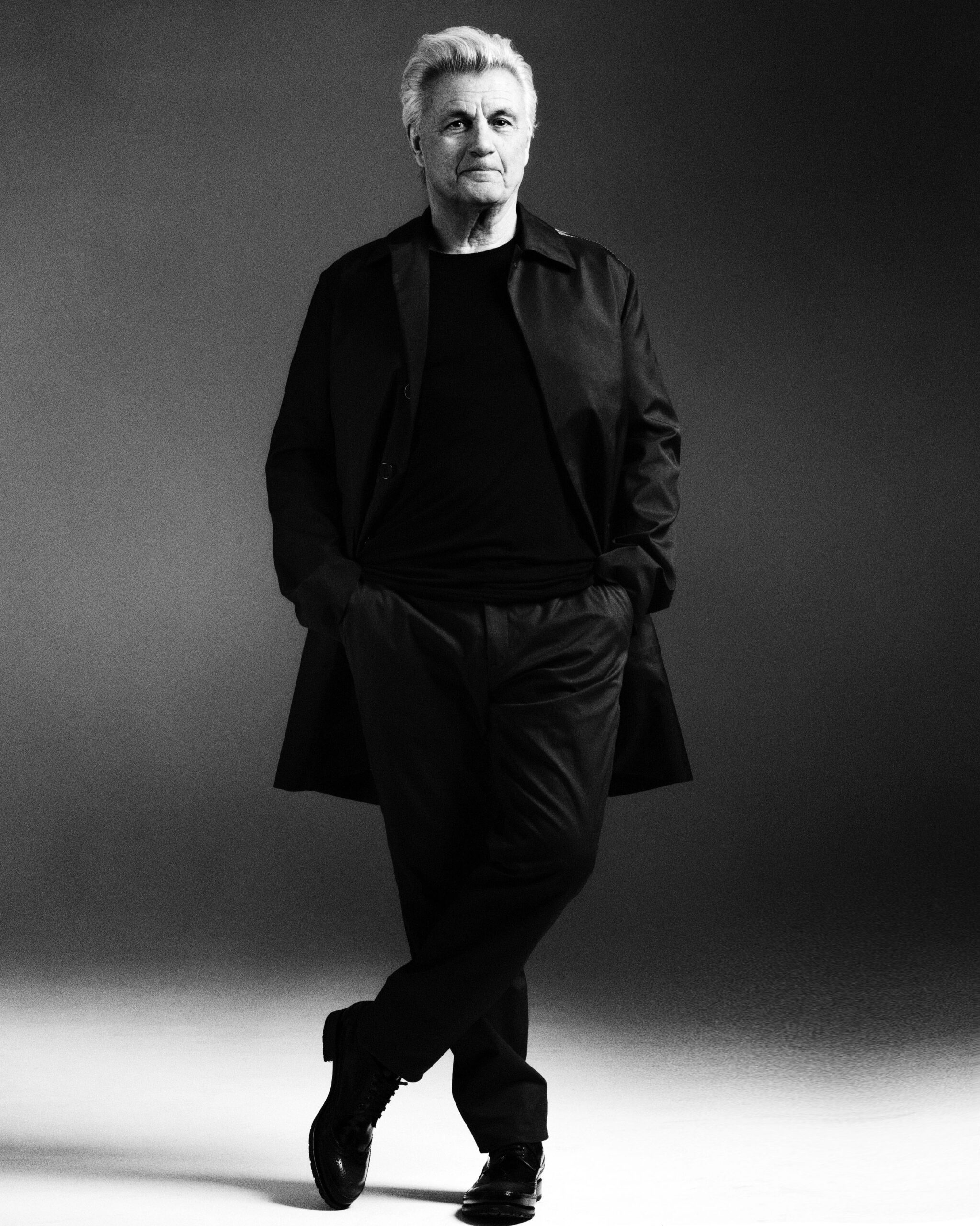

He writes all day, seven days a week. Even scuffing around in his workday ensemble of sweatpants, flannel shirt and moccasins, he’s an impressive specimen – wiry, fit, with a luxury of silver hair. A lifelong wrestler, Irving coached into his late 40s and sparred into his 60s, persisting until the only partners he could find were 20 years younger and he was getting hurt. Still, every day at 4 p.m., he heads down the hall to his home gym, where he works out until 6. The room is built around a regulation-sized wrestling mat and decorated with more photographs: wrestling shots of his two older sons, Colin and Brendan (with Shyla Leary, whom he married at 22 and divorced two decades later); and acting stills of his youngest son, Everett (with Turnbull). “And that’s me, falling on my ass,” he growls, pointing to a snap of his younger self in a wrestling singlet, splayed in mid-air.

Wrestling isn’t just a sport to Irving. It’s a way of life, a plot point in eight of his books and a key component of his identity. He sports a tattoo on his right inner forearm of the starting circle on a wrestling mat and still measures his weight to the ounce – “I’m a little lighter than usual right now,” he says, “163 and a half.” Because he was perpetually in training, he never smoked, took drugs or drank much; late last year, he quit drinking altogether. He claims it wasn’t difficult: “Giving up sugar in my coffee [while in grad school], now that was hard,” he says. “I’m not enamoured of the whole Hemingway-Fitzgerald bullshit that consumes American idolatry of writers. I think Hemingway’s an awful writer. And why did those two write their best novels when they were 27? Because they were drunks. If I’d written my best novel at the age of 27, what sort of pig would I be?”

It quickly becomes apparent that Irving likes to have as much control in a conversation as he did at a meet. His voice is thick and husky, and he speaks deliberately, as if each word were a brick; he positions them one by one until every sentence is a perfectly constructed structure. To say his answers are thorough would be an understatement: his transcribed reply to one question, about how his memory is holding up, runs five and a half typed pages. (Short answer: it’s still good.) Though he’s candid about his personal life, he much prefers jawing about his work. Just when you think you have him pinned with, say, a question about whether lust changes after mid-life – whoop, he flips you, redirecting the conversation to his characters.

“From the age of 14, I grew up with that wrestling mindset [of discipline and will power],” Irving explains. “There was something I wanted to do, and it required something of the rest of my life. I’ve always looked at writing that way, too. I’m not only dedicated to writing in the hours I give to it. It must necessarily affect the rest of my life.” As if to prove his point, he started book No. 14 on Christmas Eve.

Irving always knew he’d eventually get to AIDS. By the time he started In One Person in June 2009, the plot had been humming in his head for nearly eight years: Billy, a bisexual man in his late 60s, looks back to 1955. He was a 13-year-old boarding school student, struggling with his emerging, all-consuming sexuality, and his first love – Miss Frost, the much older librarian in their small New England town – harboured a profound secret. Irving knew what the book’s last lines would be; he always starts with his ending and works backwards. He also knew the message of those last lines: “Don’t think that by putting a sexual label on me you know who the hell I am,” he says, with a look that would flatten anyone who dared.

Yet he never thought of it as an AIDS book. “In the same way that – and this sounds crazy – I never thought of The Cider House Rules as an abortion novel,” he says. “Because those subjects were so integral from the beginning. I knew because of the time frame that many of the characters were on a collision course with the early 1980s. So AIDS was always waiting there. I think that was part of the reason I’d hesitated to write it. I lived in New York City in the ’80s and lost friends. I knew that writing about this would cause me to re-teach myself details I was rather happy to have forgotten.”

Typically, he spares none of them, including the guilt felt by the healthy; the horror of the hospice; the gruesome ravages of the virus; and the despair that Ronald Reagan’s government was ignoring it.

Irving calls himself a “slow processor” who writes better about the things that affect him emotionally and psychologically if he gives himself some distance from them. He wrote his Vietnam novel, A Prayer for Owen Meany, decades after that war ended, and he deliberately set Cider House before he was born, so he wouldn’t interweave its abortion issues with present-day politics.

Writing Garp in the ’70s, “I was angry and disappointed in what struck me as the utterly false promises of the ’60s,” Irving says. “What I was seeing, a scant 10 years after the so-called sexual revolution, was an animosity between the sexes and a hatred of sexual differences that was worse than anything I remember seeing as a kid in the ’50s. I don’t mean that In One Person is as radical a novel, socially or politically, as Garp. It isn’t. But I remember thinking when I finished Garp, ‘Thank God I’ll never have to write again about the issue of sexual tolerance or anger at sexual intolerance. That will be so over by the time I write my next book.’ How naive.”

The new novel isn’t concerned with Billy’s politics, though. It’s about his “essential solitariness.” The title comes from Shakespeare’s Richard II: “Thus play I in one person many people, and none contented.” For Billy, that means no one partner could satisfy him. “He realizes that he will always be thinking of the vagina when he’s with the penis and reaching for the penis when there’s a vagina there,” Irving says. “I love the sexual misfit, who didn’t ask to be who she or he is, but that’s who they are. I’m always looking for the margins.”

For all his love of control, Irving can make some candid admissions. Here’s a good one: “There’s always this euphoria when I begin something where I think, ‘This is really exciting, this is different,’ ” he says, chuckling at himself. “But I don’t have to get very far before I think, ‘Not this again. Shit.’ ”

So often do themes recur in Irving’s fiction that his Wikipedia page features a chart, with his books broken into categories such as New England, Vienna, Absent Parent, Writers and Sexual Variations. The Writers box is ticked for every one (the man writes what he knows). The Sexual Variations category is broken into subcategories including adultery, transsexualism and older woman-younger man. In One Person isn’t posted yet, but if it were, all the above boxes would be checked.

Just don’t expect Irving to admit that the antecedents of those recurring themes are autobiographical. In One Person focuses on a boy at a formative age, who’s beginning to figure out that adults are keeping things from him. Billy has a frosty mother, a kind stepfather and a missing father (who, he eventually learns, is a Second World War veteran). He attends a boys’ boarding school and has a formative experience in Vienna. His first sex is with an older woman. He loves theatre and becomes a writer. His grandfather, who loves theatre, too, acts in drag. All of those things – all of them – are true of Irving, too.

He was born John Wallace Blunt Jr. in New Hampshire and attended Phillips Exeter Academy, where his beloved stepfather, Colin Irving – the only father he ever knew – was on the faculty. Young Irving fell in love with Shakespeare. (In their all-male productions of Romeo and Juliet, he longed to play Juliet, but was always typecast as combative Tybalt.) He revered meaty novelists like Melville, Hawthorne, Hardy and Dickens. And he lusted after pretty much everyone.

“One reason this book took only two years to write is that, from a research point of view, it was easy,” Irving says. “I remember those terribly conflicted feelings that any young boy feels in an all-boys school, where some of the older boys are forbiddingly attractive to you. You’re attracted to everything in sight: faculty wives, your friends’ mothers. You think, ‘Jesus, can I please be attracted to somebody I’m supposed to be attracted to?’ ”

Irving’s sexual initiation, at age 11, came courtesy of an older woman. “But I didn’t think of myself as molested or abused,” he says. “I was fond of her, and when the relationship was over, I missed her. But it did make me anxious that my children be wary of sexual initiations from older people. And it did influence me – for a while after, I found younger girls less interesting than their mothers.”

Irving says of Billy, “Coming from the family he comes from, secrets obtain.” That’s true of Irving, too. Irving’s mother, Frances, now deceased, was a nurse’s aid, family counsellor and “an abortion rights activist long before Roe vs. Wade,” Irving says. “She was more like [Garp’s mother] Jenny Fields than Jenny Fields.” But she refused to speak to her son about Blunt Sr. “There wasn’t anything vicious about it,” Irving insists. “My mother loved me and I loved her. But she would say, ‘I’m not talking about that.’ Even to the point where I would tease her, ‘If you don’t, I’m going to imagine all kinds of terrible things.’ She’d just say, ‘Yes, you are.’” After Irving wrote Owen Meany, in which a secret father also factors (and which Irving dedicated to his mother), Frances did admit, “He was nothing like that man.” But she said it to Turnbull, not Irving. “It was so typical,” Irving says, laughing. “My mother would never give me the satisfaction.”

Irving knew a little about his birth father, and an older cousin passed along what nuggets he could glean – Blunt had dark hair, he was in the Air Force, he survived being shot down over Burma. But though Irving was open to meeting Blunt, he didn’t want to initiate it. “My mother was emphatic that she’d wanted him gone, and I didn’t disrespect that,” Irving says. “I wasn’t standing in her shoes in 1942. And I felt, by seeking my biological parent, I would somehow be slighting my genuine love of my stepfather.” (They’re still close – Colin Irving is one of the first readers of all Irving’s books.)

A few years ago, after Blunt died, his youngest son, Chris, contacted Irving. He filled in more details, including evidence that Blunt may have attended Irving’s wrestling matches. That struck home with Irving because there had been a period when, warming up before a match, “I would look into the crowd for someone who would be inexplicably looking at me,” he says. “Later, I used to think he’d show up at a book signing. But it never happened.” Irving is still in touch with three of his half-siblings, and a wartime photograph of Blunt hangs on his gym wall.

Married at 22, with a son on the way, Irving never imagined he would be self-supporting as a writer. Of his first three novels, only one sold into paperback, and each sold fewer than the last. “I had no reason to believe that the fourth novel [Garp], which was written in exactly the same way, would be the one that would liberate me,” he says.

“I didn’t get into it for that. It was a compulsion, an obsession. I would have written 13 novels by this point whether anybody had published them or not. You either recognize in yourself that you will never live without it – in which case, you better do everything you can about your life to feed this habit. Or you’ll always be unhappy.”

Success did come, of course. So much so that when asked to name his lowest period, Irving struggles to cough up an answer. It wasn’t his divorce; that was amicable. The first six weeks after his prostate cancer diagnosis were worrying. “But again, I don’t call that a low point,” Irving says, “Even at that time, I thought, ‘I’ve had a great life.’ ” He took his sons and grandchildren on a vacation to Cozumel, then had the surgery. He’s had no recurrence or side effects.

So the lowest ebb Irving can think of is almost laughably high: a period in the 1980s when he was single, a best-selling novelist in New York. Because his priorities were his sons, writing and wrestling, in that order, “I’m not proud of what passed for my sexual relationships then,” he says. “There were a lot of them. I was at a place where I was opposed to anything resembling a committed relationship. But I can’t say I liked myself for deliberately choosing to go out with women that I knew perfectly well I couldn’t have a serious relationship with.”

He boldly announced to his older son, who shared his apartment, that not only did he not want to live with a woman, he didn’t want any woman’s things in his home. (This led to an amusingly mortifying moment, when he threw away a dress he found in a closet, only to discover it belonged to his son’s girlfriend.) Two weeks later, he went to Toronto to read with Robertson Davies at Harbourfront, met Turnbull and promptly fell in love. “You never should embarrass yourself so much in front of your children,” he says, grinning.

The coffee has long gone cold. But Irving has one more photo to show. “It’s a non-autobiographical connection to In One Person, which I trust you will not claim is autobiographical,” he says. “It’s a test for you. We’ll see how well you do.”

He leads the way up the stairs, past a photo of a dog (whom he IDs with this classic Irving description: “He was a terrible fighter and had no eyelids, but he was a wonderful dog”) and into a bedroom. With a flourish, he points to a photo of an actor in a woman’s costume – an image, it must be said, that calls to mind descriptions of Billy’s theatre-loving, cross-dressing grandfather.

“Okay,” Irving announces impishly. “My grandfather, Francis Everett Irving. Trust me, he was not a cross-dresser. But I do remember him more vividly dressed as a woman.”

He’s autobiography, yes. But like everything in the world according to Irving, he’s really fodder. “Nothing in my life,” Irving sums up, “has ever been so important to me that I wouldn’t change every word of it to make a better story.”

A version of this article appeared in the May 2012 issue.

RELATED:

The Last Chairlift: At Home With John Irving, Discussing His Biggest, Boldest Novel Yet

Five ‘Furies’ Writers Explain The Female Archetypes That Inspired Their Short Stories

From ‘The Vagina Monologues’ to ‘Reckoning’: The Evolution of a Feminist Writer