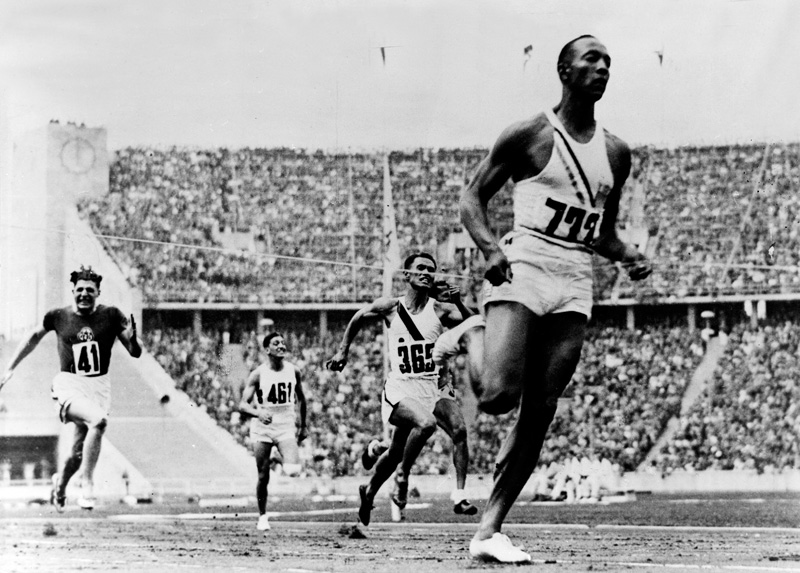

Celebrating the 85th Anniversary of Jesse Owens Winning His Historic Four Gold Medals at the 1936 Olympics

Jesse Owens not only won four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but he did so in Adolf Hitler’s backyard against the Fuhrer’s supposed master-race athletes. Photo: Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Images

It seems fitting that, a day after the Tokyo Olympics wrap up, we celebrate the 85th anniversary of the day Jesse Owens capped off his breathtaking performance at the 1936 Berlin Games, winning the long jump and capturing his fourth track and field gold medal to cement his status among the greatest Olympian athletes of all time.

Between August 3 and August 9, 1936, Owens won gold in the 100m, 200m, 4x100m relay and long jump, a record-setting performance that wasn’t equalled until Carl Lewis did it at the 1984 Games.

His triumph that day lives on as one of the greatest athletic displays of all time. But that only tells part of the story.

The fact that he performed this magnificent feat as a Black man from the segregated U.S. South, and won his golds in Adolf Hitler’s backyard against the Fuhrer’s supposed master-race athletes, makes it an accomplishment that will be celebrated forever.

His golden performance proved to the world that Black athletes should compete in the biggest sporting competitions. As the first Black U.S. athletic superstar, he had a transformative effect on race relations in his own country.

“Owens made it acceptable for the entire nation to support an African-American as a role model,” writes one historian of the role the Alabama sharecropper played in helping to end the bigotry that was so embedded in that country’s psyche.

It’s also fair to say that his momentous efforts single-handedly paved the way for future track stars, like Canada’s own gold-winning track medallists: Donovan Bailey, Andre De Grasse and Damian Warner.

Using his own words, we celebrate the life and accomplishments of one of the world’s greatest sporting icons.

The Starting Line

James Cleveland Owens was born on Sept. 12, 1913 in Oakland, Ala. His parents were sharecroppers and his grandparents were slaves and, like his forebears, young Owens spent his early life helping his impoverished family by picking cotton. As a youngster, he went by his initials “J.C.” but, when one of his early teachers mispronounced that as “Jesse,” the moniker stuck with him for the rest of his life.

The family later moved to Ohio where Owens began attracting attention for his athletic skills, tying the world record for the 100-yard dash when he was still in high school. His prowess on the track won him a spot on the Ohio State University track team where, despite the fact he led the Buckeyes to eight NCAA championships, he was forced to stay in separate hotels and eat in segregated restaurants.

The Race to Olympic Immortality

When Berlin hosted the 1936 Olympics, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler used the games to solidify his grip on power and to promote Nazi propaganda to the world. A key tenet of his movement was Aryan “ethnic purity,” the notion that Germans were the master race and its athletes were superior to all others, including Jews, Blacks and other “non-white” people.

Owens was under enormous to skip the event, including from the president of the NAACP, urging him not to lend participate in an event hosted by such an outwardly racist regime. Owens did join calls for the U.S. to boycott but, when that was squelched, the American delegation — he and 17 other Black athletes — had no choice but to compete in front of the hostile audience. Over a period of six days, he put lie to Hitler’s racist theories, winning the 100m, 200m, 4 x 100m relay and long jump, a quadruple gold effort that stood until Carl Lewis pulled off the same feat in 1984.

It was his awesome showing that proved to the world beyond all doubt that Black athletes could not only compete with, but also outperform, white athletes. Despite the fact that the Nazi officials tried to downplay his accomplishments, Owens’ record-setting performance in such a hateful arena made him a globally respected figure. “For a time, at least, I was the most famous person in the entire world,” Owens said of the global phenomenon he became after Berlin.

Sportsmanship Begets Friendship

“Hitler must have gone crazy watching us embrace.”

During his time at Berlin Games, Owens developed an unlikely friendship with Luz Long, the celebrated German long-jump champion. In fact, Long was instrumental in helping Owens win the long jump event. Owens had fouled on his first two jumps and a third fault would have eliminated him from the event. Before his third jump, Long advised Owens to “change his mark” and start his jump earlier.

Using this advice, Owens was able to qualify for the final and eventually defeated Long to win his fourth gold. After Owens’ winning jump, the German silver medallist publicly risked offending Hitler and Nazi officials who were watching from the stands and rushed forward to shake hands with the Black U.S. athlete. The pair walked around the stadium linking arms. “It took a lot of courage for him to befriend me,” said Owens of his relationship with Long. “You can melt down all the medals and cups I have and they wouldn’t be a plating on the 24-karat friendship I felt for Luz Long at that moment.”

The pair remained friends after the Olympics until Long was killed while serving in the German army during the Second World War. In his final letter to Owens before he died, Long signed off: “Your brother, Luz,” a testament to the strong bond that had somehow grown between the two competitors despite the ugly forces of race and nationalism in which it was forged.

Return to America

Had Owens lived today, he would have been able to parlay his Olympic glory into lucrative endorsements, making big money from television appearances, gracing cereal box covers or selling running shoes. But Owens, who was only 22 at the Berlin Games, returned to his home country with no job offers and even bleaker prospects. He also had to support his wife, high-school sweetheart Minnie Ruth Solomon, and growing family.

“After I came home from the 1936 Olympics with my four medals, it became increasingly apparent that everyone was going to slap me on the back, want to shake my hand or have me up to their suite. But no one was going to offer me a job,” he recalled. Owens was forced to take various jobs to support his family including pumping gas, serving as a janitor and working at a dry cleaners before he declared bankruptcy.

After unsuccessful stints working in public relations for Ford and promoting a Negro League Baseball team, he had no choice but to accept humiliating paid stunts, such as running against dogs, cars or horses. “People say that it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do?” he asked bitterly, a familiar lament made by many star Black athletes of the time.

Presidential Snub

When Owens died in 1980 at the age of 66, he still hadn’t received an apology for a snub he received from the White House back in 1936. Today, politicians will stop at nothing to pose in photo-ops with decorated Olympians. But after the Berlin Games, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt didn’t bother to send a congratulatory telegram or invite Owens to the White House, privileges FDR bestowed on other U.S. athletes. “He never got any recognition from the President at the time,” his daughter Gloria Owens Hemphill said in this 2016 newspaper feature. “He returned from the Olympics to a country where in some parts you still couldn’t ride on the front of the bus or live where you wanted.”

Future U.S. leaders attempted to correct FDR’s slight. In 1975, President Gerald Ford awarded Owens the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour given by the US government. In 1990, President George H. W. Bush posthumously awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal.

But it wasn’t until 2016 that President Barack Obama finally righted his predecessor’s terrible wrong by inviting the surviving members of Owens’ family to the White House for a reception to honour the great Olympian and his 17 teammates for their heroic showing at the 1936 Olympics.

“It wasn’t just Jesse. It was other African-American athletes in the middle of Nazi Germany under the gaze of Adolf Hitler that put a lie to notions of racial superiority—whooped ’em—and taught them a thing or two about democracy and taught them a thing or two about the American character,” said Obama, recognizing the heroic role Owens played in 1936.

RELATED: