National Indigenous Peoples Day: How Local Food Connects Indigenous People to Their Language, Knowledge and History

Sheila Flaherty is founder of the Iqaluit-based harvest-to-table culinary tourism venture sijjakkut (“by the seashore” in Inuktitut) and the first Inuk chef to appear on MasterChef Canada. Photo: Frank Reardon

To celebrate National Indigenous Peoples Day, we revisit this recent feature story from Zoomer magazine, in which five Indigenous visionaries explain what traditional foods — from maple to muskeg — tell us about the past, and how they relate to Reconciliation in the present.

The first time I heard the Nuu-Chah-Nulth phrase hishuk ish tsawalk (everything is one) was on a hike with Gisele Martin, ta citizen of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, in the woods behind the community hall in Tofino, B.C. As we walked, we tasted tiny tart berries and needles from a hemlock tree, which Martin’s ancestors have foraged off the wild coastal land for thousands of years.

In this small world, everything is indeed one, but few things capture this more effectively than food. It is nourishment, physical, spiritual and emotional, but it’s also the foundation for hospitality, commerce, language, ceremony and so much more.

Although the word “food” doesn’t appear once among the 94 calls to action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, Indigenous peoples’ relationship to it infuse all six themes: health, language and culture, education, employment, land sovereignty and conservation.

Food is such a relatable and important pathway to better understanding and relationships between peoples. From maple to muskeg, these five Indigenous visionaries explain what traditional foods tell us about the past, and how they relate to Reconciliation in the present.

Scott Iserhoff / Goose

“My grandparents played a major role in my food journey,” says chef Scott Iserhoff, a Mushkego Cree and founder of the Edmonton-based food and educational company Pei Pei Chei Ow. “Back home, we have an annual hunt for geese every April called the Niska Pisim, or Goose Moon,” Iserhoff says. “Goose is our main staple. I remember watching my grandmother pluck geese. I would watch her hands, and she put so much care into what she was doing. My aunties, my mom, we would pluck them and then my grandfather would smoke them, and we would make a stew from it.”

Iserhoff, who grew up in Attawapiskat First Nation and Moose River, Ont., found his calling through this annual family rite. “For Indigenous people, food is our way of life. The way the animals migrate dictates how we eat. It’s a huge integral part of our identity.”

But when he went to culinary school, Iserhoff couldn’t connect with what he was learning. “When I cooked French food, it was just … food.” In 2018, Iserhoff – who had, by then, moved to Alberta – launched Pei Pei Chei Ow to give Indigenous youth and other chefs a taste of what he’d grown up with.

“Pei pei chei ow means ‘robin’ [in Omushkegowin, or Swampy Cree]. That’s a name my grandfather gave me when I was a kid, because I talked a lot. Robins are messengers. When spring comes, that’s all you hear. And that’s when I would visit my grandparents.”

Now he leads programming for Indigenous chefs, youth and the general public, such as “Cooks with Stones,” with Stoney Nakoda Nation and Pursuit Group in Banff, and free cooking classes with the Edmonton Public Library. This summer, for the first time, he brought on two interns, both Indigenous culinary students who reached out to Iserhoff because they’d heard what he was doing.

“I’m providing a space that I never had coming out of college and working in restaurants,” Iserhoff says. Now, he’s not only helping to foster this critical connection for others, but also reaffirming his own identity.

“Cooking my food, I’ve grown so much as a person. I’ve gained back [Cree] words that I haven’t spoken in 30-plus years,” he says. “I feel more confident. I feel happy with what I do, cooking all the time, cooking my food.”

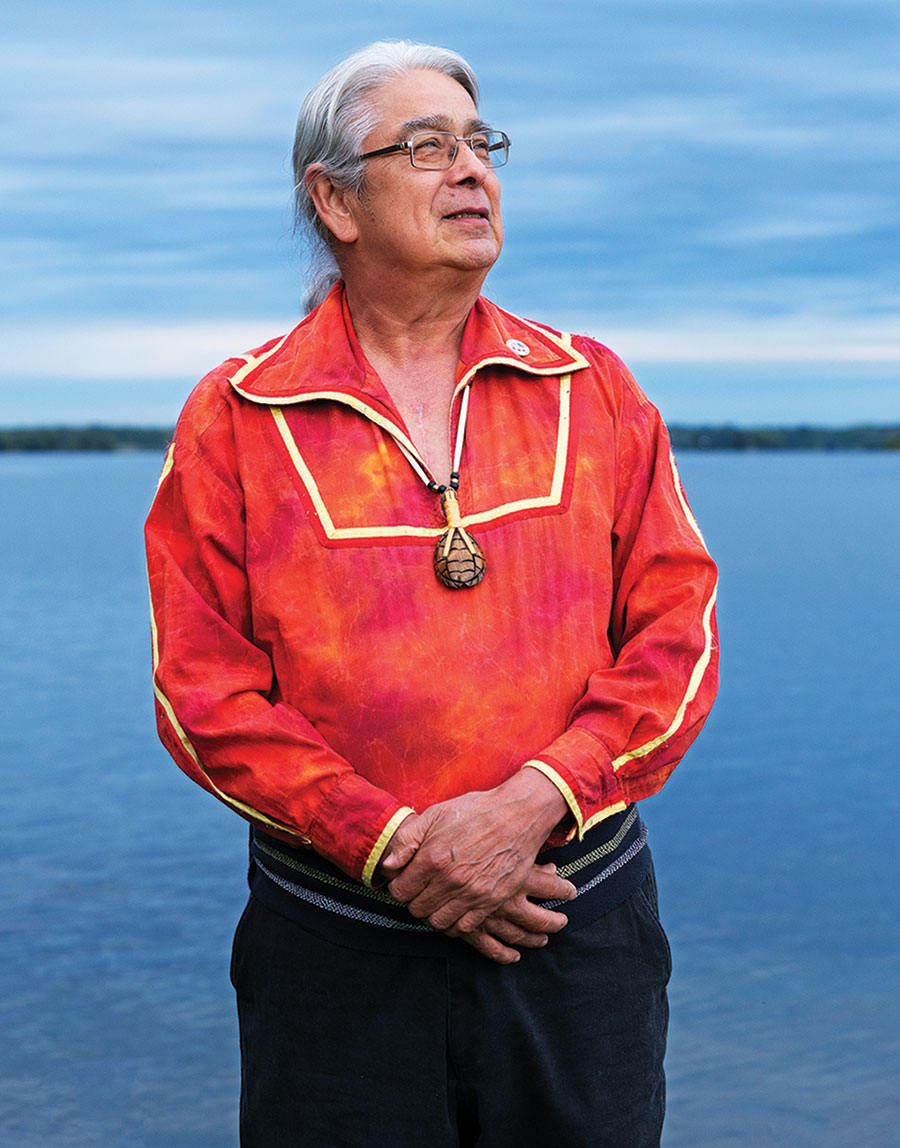

Dr. Henry Lickers / Maple Syrup

“How far back does the use of maple go?” Dr. Henry Lickers chuckles. “I’ve been interpreting the legends for years, looking at them as a biologist and seeing what I can glean. From what I can tell, our maple legend probably goes back to the Ice Age, 12,000 to 15,000 years ago. When the Creator looked down, he saw us, the Haudenosaunee people, really tired from the long arduous journey from the south, after the glaciers retreated. And so he asked the maple tree to produce syrup for us, to give us strength.”

A Haudenosaunee citizen of the Seneca Nation’s Turtle Clan, Lickers grew up listening to his grandparents and great-grandmother tell these stories. “One of the things they stressed was that each one of those legends has knowledge about how to live in the environment,” he says. As an adult, Lickers fell in love with science because it gave him a framework for all those childhood learnings.

While his education took him to the University of Waikato in New Zealand, it was during his decades as a member of the Eastern chapter of the Ontario Maple Syrup Producers Association, and through his work as an environmental science officer and a director of the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, that he tapped into what he believes is the greatest opportunity to protect the maple tree from the destructive forces of climate change and deforestation.

“When I talk to people who live off the land, they see the Earth as their mother. It’s just like talking to my grandfather. It made me realize, ‘Holy smokes, colonizers believe what I believe.’” That aha moment helped Lickers to crystalize the naturalized knowledge system, a way to share environmental expertise between young and old, settlers and Indigenous people, rooted in the Haudenosaunee’s Great Law of Peace (a foundation for democratic governance), that he had contemplated most of his life. Lickers used this framework to promote collaboration between maple syrup producers, and he frequently speaks about it in lectures at business schools and conferences. (He also leans on it in his current role as the first Indigenous commissioner for the International Joint Commission, the Canadian-U.S. organization that manages lakes and rivers shared by both countries.)

For generations, the Haudenosaunee used sealed birch bark containers to engineer a reverse osmosis effect to purify syrup; iron pots and steel needles brought by settlers made the now-common process much easier. Lickers says there’s much to be learned from collaboration, a common practice among syrup producers, both Indigenous and settlers, in his region.

“They say knowledge is powerful, but for us knowledge is powerful only if it’s shared,” he says. “You have to have reciprocity. You each have to benefit. The way we share knowledge – you can implement that all the way down to the individual sugar bush.”

Lila Fraser Erasmus / Muskeg Tea

“I would like to go up and down the Mackenzie Valley, making sure that everyone understands and has access to medicine and knows how to make their own,” says Lila Fraser Erasmus, who owns and operates Naturally Dene in Yellowknife.

A descendant of the Dene Cree from Fort Chipewyan, Alta., on her father’s side, and a member of the Nacho Nyak Dun Wolf Clan from Mayo, Yukon, on her mother’s, Fraser Erasmus says it’s not the scarcity of ingredients that grow in the boreal forest around her home that make it so difficult for Dene to practise generations-old healing practices. It’s the knowledge required to do so.

Take tea made from muskeg, one of the most abundant and commonly used plants in her region. “It keeps cough away, clears up colds and congestion,” she says. “And it’s evergreen. You can get muskeg tea all year round. Early June is when the new growth starts. When the snow melts and everything starts to go green and the juices start to flow, you’ll see these white little tufts of flowers. Those are really great for skin conditions, really nice in teas.”

For Fraser Erasmus, who holds a master’s degree in dispute resolution and previously worked as an assistant negotiator and manager of community justice for the Northwest Territories government, harvesting and using muskeg tea has connected her to the teachings of her Ancestors. “We’re filled with knowledge, but that knowledge doesn’t come from a textbook,” she says. “As Dene, we walk with guidance from the spirit world. We understand our environment to include those we cannot see or touch, the old ones who have gone before us. If you’re being led to places on the land, that’s our Ancestors walking with us, whispering to us, ‘There’s medicine over here.’ In return, we show our gratitude by offering tobacco or a gift to the land, acknowledging and thanking it for its guidance.”

Establishing the knowledge systems so the next generation can access the wisdom of the ages – something she’s trying to accomplish by leading medicine walks and workshops at Naturally Dene – is as important for her people’s well-being as is conventional health care. And she’s advocating for it to be treated as such.

“Our health system should be reflective of the people it serves,” she says. “We are a majority here. But our institutions don’t recognize our own medicines, our ways of doing. That tells us these institutions don’t serve us as Dene. Once our people start accessing land medicines, the knowledge will return.”

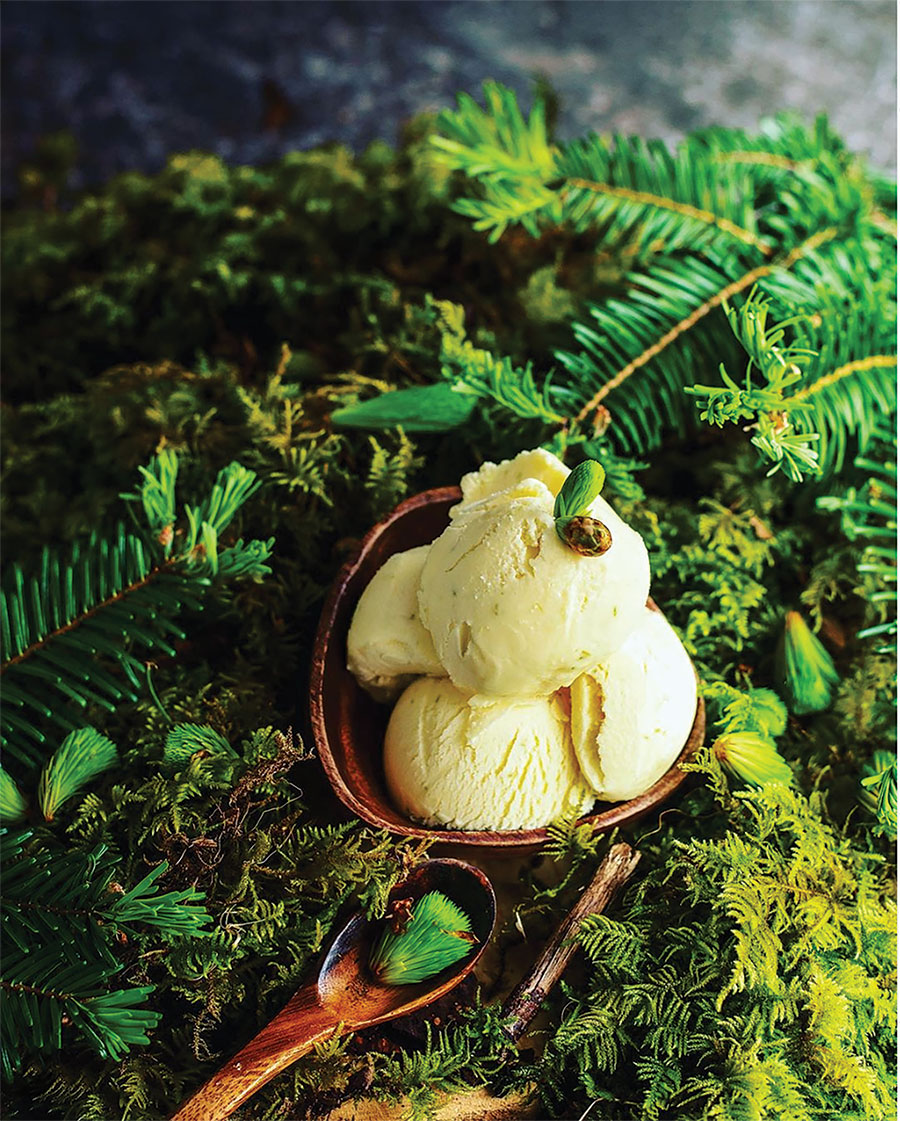

Kirsten Wood / Spruce Tips

At Blue Spruce Ice Cream in Courtenay, B.C., the frosty treat is more than a foodie trend. For owner Kirsten Wood, the signature spruce tip flavour – made from Sitka spruce buds Wood forages from the Comox Valley – is not only a conversation starter, but also a connection to Indigenous food systems.

“The most common question we get when people come in and see spruce tip ice cream is, ‘What’s that? You can eat spruce tips?’ So, we ask them if they want to try it, and pretty much everyone likes it,” Wood says.

A potent source of vitamin C, spruce buds have been used by Indigenous people for generations, steeped in tea, dried and even candied. In ice cream, the tips impart a lemony, melon flavour.

“People are so interested in local food right now,” Wood says. “Well, local food is Indigenous food. This is a way to help people understand that these local ingredients they’re interested in were used by people who were here before, for medicinal purposes and all sorts of things. It’s a way to honour that history.”

Ice cream might sound like an unconventional way to go about it, but Wood, a citizen of the Saddle Lake Cree Nation on her mother’s side, is proud to be forging new paths as an Indigenous business owner. “We’re seeing a resurgence of Indigenous role models, especially in food, and that wasn’t something that was accessible to us before,” she says “Years ago, my grandmother wouldn’t have been able to own a business – it wasn’t allowed. I didn’t have to make this part of my mandate, but this is my identity.”

Sheila Flaherty / Seal

“Seal is an intrinsic part of being Inuk,” says Sheila Flaherty, founder of the Iqaluit-based harvest-to-table culinary tourism venture sijjakkut (“by the seashore” in Inuktitut) and the first Inuk chef to appear on MasterChef Canada. “Seal is a source of food. It clothes us – parkas, mitts, pants and boots. It’s our whole way of getting nourished and staying warm,” she says. “We don’t waste any part of an animal. We make use of everything.”

Flaherty didn’t set out to make food her life’s work. In her previous career, she was immersed in Inuit rights, research and policy, and about to enter her first year of law school when she met her husband. Moving to Iqaluit, she started experimenting with Inuit food. One of her first forays was sushi rolls made with Arctic char caught by her husband – who speaks Inuktutit as a first language and grew up on traditional foods in Ausuittuq, the most northerly community in Canada – because she missed the international cuisine that was so readily available in the south. That led to selling sushi rolls on Facebook and a last-minute decision to audition for MasterChef the night video submissions were due.

“I got eliminated in the first round, but it showed there’s space for someone like myself who focuses on Inuit food. That’s where the idea for sijjakkut was birthed.”

When she opens the doors to sijjakkut, a planned 4,000-plus square-foot [370-square-metre] facility that will include a teaching kitchen and bed and breakfast, she hopes to promote Inuit traditional practices and knowledge – not only for visitors, but for her community. “My husband has a great thought to fly in elders from different communities to stay at our bed and breakfast and share their knowledge on food preparation. And wouldn’t it be also amazing to have cooking classes for Inuit women? We could provide child care and tax vouchers so there are no obstacles.”

She also hopes to replicate one of the best experiences she’s had as a chef, when she participated in an experimental culinary camp focused entirely on seal in Nuuk, Greenland. “There were five chefs, and we spent eight days in a food lab working with seal meat in new ways. I can’t even remember how many types of offerings we prepared. I want to have events like that to celebrate Inuit culture and expand on traditional ways.”

A version this article appeared in the April/May 2023 issue with the headline ‘Roots of Identity’, p. 78.

RELATED: