Fifty-one years ago today, on July 20, 1969, American astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed their lunar module, Eagle, on the moon’s Sea of Tranquility and became the first humans to step on the surface of the moon. Jim Slotek commemorated the achievement on the 50th anniversary of the moon landing and we revisit that story here.

Everyone old enough to remember it experienced their own moon landing. Mine was in Transcona, Man. (now a Winnipeg suburb), in glorious black-and-white on a 26-inch Fairbanks-Morse, bought when I was born, a year after Sputnik.

On July 20, 1969, my mom and I watched transfixed as Neil Armstrong took those few steps down the ladder from the Lunar Module. “Is he going to sink?” she asked, with genuine concern.

Between staring at this amazing event and fruitlessly trying to capture images off the TV screen on an old box camera, I don’t remember hearing Armstrong’s famous botched line.

Words were white noise. There was only this mind-boggling reality, happening live, a quarter of a million miles away.

I was space crazy. I made a scrapbook of Apollo 11 news clippings from liftoff to splashdown from the Winnipeg Tribune (I was a Trib paperboy). At school, I doodled rockets and starships (I’d been glued to all three seasons of Star Trek).

Came the end of Grade 6, I was one of two candidates for top student, and my teacher interviewed both me and Donna D., a classroom friend with almost identical marks.

What did we want to do as adults? I told him excitedly that I wanted to work in space. This was all happening fast. There’d be more and more people needed. Maybe there’d even be a settlement on the moon.

The disappointed look on his face told me I’d given him what he considered a childish answer: astronaut. Donna told him she wanted to be a journalist. She won. (Ironic side note: Our teacher, Art Miki, went on to become famous for seeking and achieving redress from the government for the wartime internment of Japanese-Canadians. I interviewed him then — as a journalist. I have no idea what Donna ended up doing.)

So, I never got into space. And my enthusiasm was misplaced. As the Cold War abated, so did our society’s desire to boldly go anywhere (with humans anyway). The moon missions ended in ’72 after Apollo 17. People fell off the space-race bandwagon like Leaf fans in May.

But for some of us, the spark remained. I was excited beyond words at those first photos from the surface of Mars by the Viking 1 lander in 1976.

And even though I never went to space, space seemed to follow me. I was at the Ottawa Citizen in 1983 when the shuttle prototype Enterprise visited the city on the back of a jumbo jet. I was driving down the Queensway when all traffic stopped, and people got out of their cars to watch the approach (which looked like two giant insects mating in flight).

I did get to meet actual astronauts. Apollo 17’s Eugene Cernan, the last man to walk on the moon, was a consultant on the TV miniseries Space (based on James Michener’s novel), and I chatted with him at a Los Angeles reception. I asked him if he ever thought they should have sent a poet to put into words what he was seeing. “All the time,” he said.

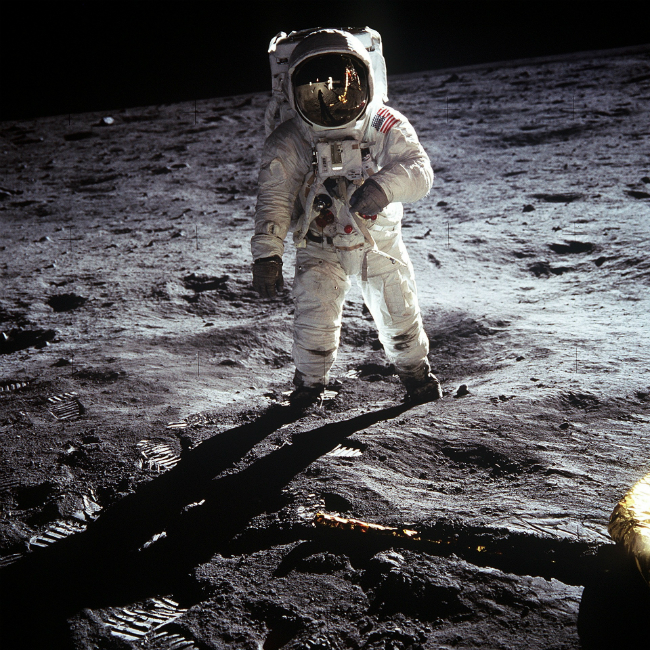

And I met the second man on the moon, Buzz Aldrin, in the strangest circumstance, at Star Trek 30: One Weekend on Earth in Huntsville, Ala. , marking the 30th anniversary of the show and bringing together the casts of every Trek series to that point. Buzz worked the parties and wore a cheesy Starship Enterprise tie the entire time. He was ebullient and social and not at all the jerk Corey Stoll played him as in Damien Chazelle’s First Man. (Although Aldrin did once punch a guy who screamed at him to admit the moon landing was a hoax. So, he was probably better to party with than to cross.)

But the real bonus to that trip was a side visit to the Marshall Space Flight Center. It’s known as the astronauts’ training centre (home to the 1.3 million-gallon Neutral Buoyancy Simulator tank, which replicates weightlessness and gives trainees an opportunity to learn to use tools while floating).

Horace Bibb, an elderly guide with an impenetrable ’Bama accent, lit up when he heard I was Canadian. He remembered Canada’s Dr. Roberta Bondar training there and talked ceaselessly about “Budda Bonda” for 15 minutes before I figured out what he was talking about.

But they were also hard at work constructing the Habitation Extension Module living quarters for the International Space Station. We were separated from the construction by Plexiglas, but there was an exact mock-up we could squeeze into to imagine life in space. And we learned the source of their drinking water (distilled from humidity in the air and urine).

The urinals in the public washroom had a sign above them that said, “Thank you for your contribution.” Said contributions were filtered into a nearby water cooler, from which we were offered a drink. I declined. That’s one astronaut test flunked by me.

And then, of course, there was the inevitable trip to Orlando, Fla., with the kids with a side trip to Cape Canaveral to see the space shuttle Atlantis (set for launch but postponed due to weather) and walk along an entire Saturn V rocket lying on its side. (Parents: as a cool kid bonus, the Space Center grounds have thousands of alligators, many of which just lie sunning themselves at the side of the road.)

So why did we stop going anywhere? As the Soviet Union teetered, there was no geopolitical reason to claim outer space. But money is probably an even bigger reason. Both George W. Bush and Donald Trump have made empty JFK-like announcements “committing” to missions to Mars and the moon. But they both also cut taxes for the rich at the expense of public coffers. So, we may not go back there until Elon Musk does.

In the meantime, we have (cheaper) mechanical eyes and ears encountering strange new worlds. We’ve landed probes on Titan and various asteroids, we’ve sent two probes — Voyager 1 and 2 — out of our solar system into interstellar space (although they’re aimed at no particular stars) and dropped multiple landers and vehicles on Mars (three of which crashed).

After a while, you tend to anthropomorphize these automatons. Earlier this year, the Opportunity Rover died in a global Martian dust storm after 15 years of sniffing about and phoning home.

Its last words, translated from code, were, “My battery is low, and it’s getting dark.”

I half-expected to hear the words of the HAL 9000 computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey, “Will I dream?”

Never stop dreaming, little guy.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2019 issue with the headline, “It Was 50 Years Ago Today,” p.44-46.