Why I Might Be Among the Last to Celebrate the True Meaning of Labour Day

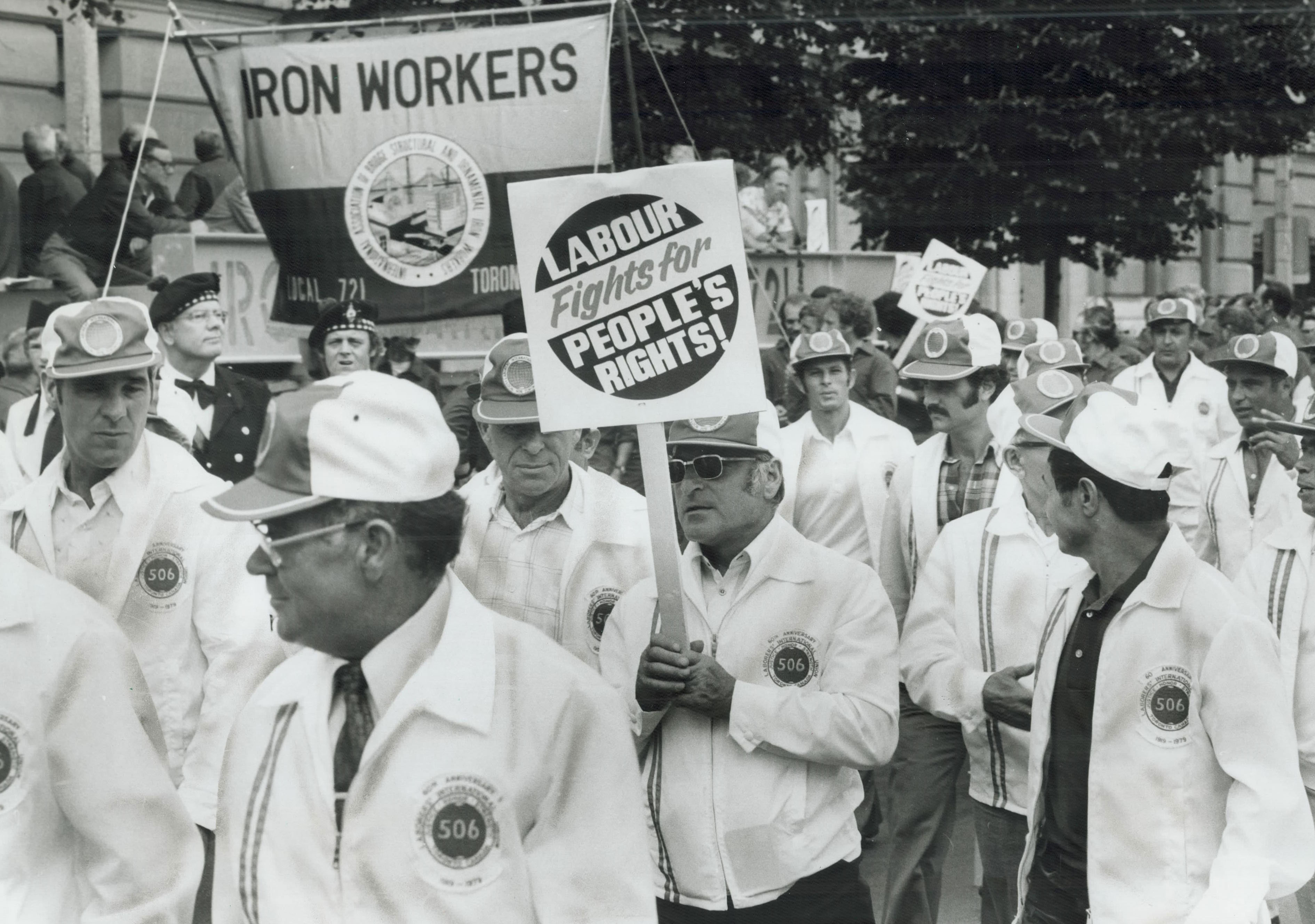

Union members are shown attacking the provincial government's planned spending cutbacks in 1979. (Photo: Jim Wilkes/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

On this Labour Day weekend, I am collecting a first-time company pension because — and only because — in 2003, 12 colleagues and I put our jobs on the line to start a union drive at the most anti-union newspaper in the country.

It’s not a spend-my-life-on-a-cruise-ship pension. I took a haircut on the amount because I took an early buyout, succumbing to the pressure many fifty-somethings are subjected to in the workplace these days. (Statistics Canada has estimated that nearly 160,000 people aged 55-64 are laid off annually. That figure does not include voluntary departures like mine.) Moreover, there’s a further cut to your pension if you want your spouse to continue to receive it after you die.

But again. After two decades in a job with no union, what the company laughingly called my “pension” was valued at $24,000 total. Just 13 years with a union, paying into a defined benefit plan, and I’m now receiving a four-figure monthly stipend for the rest of my life and my wife’s. Add in my Canada Pension Plan payout and, in a few years, Old Age Security, and it starts to resemble a livable income, even in a big city.

The bad news, especially in the private sector, is that those of us receiving workplace pensions are literally a dying breed. It’s been estimated that only 40% of retirement age people have an employer pension to fall back on.

There are ancillary losses to leaving your job before age 65 as well — including the loss of coverage for prescription drugs, dental work, etc. Yes, many non-union workplaces have basic benefits. But many are clawing back the coverage, now that — after years of orchestrated corporate propaganda against unions — there’s relatively little fear of workplaces organizing.

Companies are also becoming skilled at maximizing the hourly use of “part-time” employees, who typically don’t receive benefits. And even if they mess up on the fine-print, labour laws aren’t the kind of laws where you call the police and say, “My boss made me work 50 hours this week. Can you come and arrest him?”

So, if you don’t have a company pension to add to your retirement income, it’s a good thing you’ve saved enough to make up for it, right?

Sorry, that’s a rhetorical question. A study by the Broadbent Institute last year suggests that fewer than 20% of retirees have enough savings or RRSPs to last even five years. And Canadians, once considered among the most frugal people in the world, are now light on their savings, with some $500 billion in unused contribution room in individual RRSPs.

And if that’s the state of our retirement finances now, after a lifetime of work, the generation of young workers coming up behind us are facing the consequences of this dismantling. The good news: CPP payouts are rising, and are expected to be 50% higher when Millennials retire.

The bad news: almost everything else. The “gig economy” means young people typically don’t have one employer, they have several, none of whom owe you anything more than that day’s freelance pay.

And a regular desk job may be not much better. During my stint as a union rep, our newsroom absorbed the staff of a free subway daily — young writers and editors, most in their 20s and early 30s. The contract required that if they were going to work in our newsroom, they had to become union members. For some, that meant salary increases of between $10,000 and $15,000 (oddly, the look on their faces was like, “What’s the catch?”). When I got around to explaining their benefits package, they looked at me like we were discussing alien technology.

And pensions? I will confess I paid little to no attention to the idea until my ‘40s. Youth is a temporary condition, but most people don’t realize this until the condition has passed.

So, I’m not criticizing the Millennials in our workplace for my inability to sell them on going for the bigger paycheck deduction now in exchange for security down the road. (In a tragically ironic twist, one twenty-something I did convince to go big on financing her future, was diagnosed with a brain tumour at 26 and didn’t live to see her 30th birthday.)

But it is a cornerstone of far right, corporate-driven ideology that pensions — particularly the government kind — are wrong-headed use of people’s own money. In their ideal world, that money would remain in workers’ hands to be invested themselves. And if these uneducated investors ultimately messed up their self-directed retirement finances, well, that’s what the curb is for.

Next Monday, in cities around the country, hundreds of thousands of unionized workers will march in the annual Labour Day Parade. I’ve marched in it, along with my sons, and it isn’t exactly the Raptors’ Victory Parade in terms of attendance. There will be small groups of people cheering the marchers on along the way, and the odd heckler ranting about lazy union members and socialists.

The marchers’ ranks diminish every year (37.6% of Canadian workers were unionized in 1981 versus 28.8% three decades later, according to StatsCan). And the state of being employed — and subsequently of being retired — has suffered for it.

But for now, I am grateful to my workmates for the leap of faith we took 16 years ago — and I’m taking my gratitude to the bank.