As “Wealth” Becomes a Four-Letter Word, Billionaire Bloomberg Enters Democratic Race

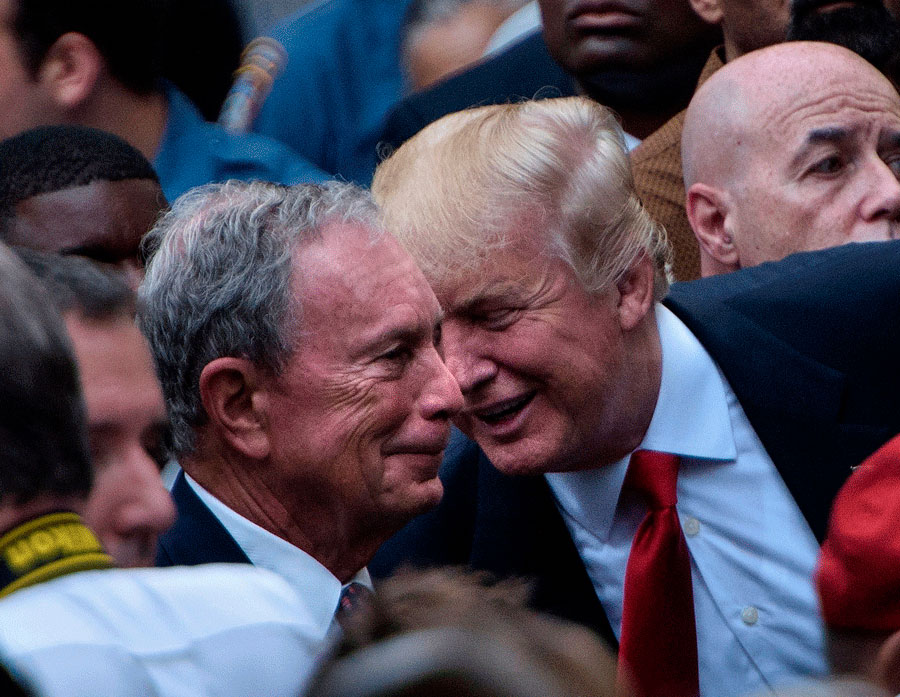

Photo: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

With Michael Bloomberg throwing his hat into the ring for the Democratic nomination, 2020 could see a first in U.S. history — two billionaires facing off for president of the United States.

If Bloomberg, 77, wins the nomination and Donald Trump survives impeachment — neither of which are guarantees — the 2020 presidential elections would pit a candidate whose estimated net worth is $53.4 billion (the eighth wealthiest American) versus an incumbent worth somewhere between $2.8 and $3.1 billion (depending on tax returns that he never gets around to releasing). In fact, it’s been suggested that should Bloomberg, whose affluence makes Trump look like a punter, goes on to become president, he will be the second richest politician in the world, ahead of the oil-rich Middle East sultans and trailing only Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

Bloomberg’s late entry into the crowded field of Democratic candidates is being cheered by many, who see him as being the strongest opponent in the field, the best-positioned to beat Trump. After building a publishing empire, he went on to become a highly popular three-term mayor of New York. Finally, the Democrats have a squeaky clean, well-known, pro-business, progressive-yet-moderate candidate who should appeal to both middle American and Wall Street, a Trump-like figure without the personal baggage or trail of corruption.

In a normal election cycle, Bloomberg’s political experience, superior communication skills, powerful connections and deep pockets would put him well ahead of the field. And unlike any of the current candidates, he alone has the resources to offset the spending advantage that Trump, who is believed to have funnelled $100 million of his own money into his 2016 campaign chest, normally enjoys.

But Bloomberg’s infinite wealth is increasingly seen as an impediment rather than an asset. Whether the candidate is a respected publishing magnate like Bloomberg or a crooked real estate hustler like his putative opponent, the old adage that “politics is a rich man’s game” is no longer acceptable, at least on the left side of the political spectrum. In politics, owning unlimited assets is no longer an asset. You can no longer buy democracy.

Society, it seems, is no longer prepared to celebrate the “champagne wishes and caviar dreams” of billionaires. Whereas once the fact that Bloomberg is Jewish might have played against him, now it’s the incomprehensible size of his bank account that is making people uncomfortable. Ironically, despite his record of spending his own money fighting climate change and gun control — which normally make him a hero among rank-and-file Democrats — the fact that he’s so affluent negates those efforts.

That’s because so-called “wealth gap” between the rich and poor has never been more stark. Besides an outpouring of loathing against their ridiculously opulent lifestyles, there’s a growing movement of voters who want to upend the system of tax breaks and loopholes that has allowed them to stockpile massive fortunes over multiple generations. In today’s lexicon, opulent lifestyles are described as “incomprehensible,” “obscene” or even “immoral.”

Just listen to the voices coming out of the Democrat primaries calling for a tax on wealth.

- “I don’t think billionaires should exist,” Bernie Sanders, who’s running for the Democratic presidential nomination, recently told The New York Times.

- “Billionaires are making their money off their accumulated wealth, and it just keeps growing,” said Elizabeth Warren, another Democratic frontrunner, in a recent debate.

- “Are we comfortable with a society where someone can have a personal helipad while this city is experiencing the highest levels of poverty and homelessness since the Great Depression?” ponders Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

And globally, the sentiment against the super-rich is equally fierce.

-

- “No one needs or deserves to have that much money. It is obscene,” John McDonnell, a Labour Party MP in England, said of billionaires in a recent speech.

- “The problem is that decisions have been made that have made it easier and easier for those at the very top, the very powerful, not to contribute their fair share. And it has a cost. People pay the price,” said NDP leader Jagmeet Singh in his recent federal campaign.

Which billionaire can you stomach?

Bloomberg’s Democrat opponents have been quick to tar him with the anti-rich feeling that’s percolating through the ranks. “We do not believe that billionaires have the right to buy elections,” said Sanders. “That is why multibillionaires like Mr. Bloomberg are not going to get very far in this election.”

And Warren was even more critical, saying the super-rich “Bloomberg doesn’t need people. He only needs bags and bags of money.” And that if he wins the nomination, the 2020 election will come down to a choice of “which billionaire you can stomach.”

Indeed, candidates like Sanders and Warren are proposing massive tax changes for the super-rich that would see the richest Americans pay their fare share. It’s called a wealth tax and it’s quickly gaining traction not only in the U.S. but around the world. Warren’s proposal, which has had the most visibility, not only consists of closing tax loopholes, tax shelters and raising corporate taxes, but it would go after the fortunes of the wealthy, a two per cent tax on households worth more than $50 million, three per cent on households worth a billion. She claims that her wealth tax would raise $2.75 trillion.

With calls on Bloomberg to adopt a wealth tax as part of his platform creates the dizzying but intriguing prospect of a politician who spent a lifetime building his fortune to epic proportions to promote measures that would put a major dent into his own bank account, not to mention those of his friends and benefactors. (To be fair, in Bloomberg’s first TV ad, he promotes a wealth tax that will allow the “middle class to get their fair share.”)

A wealth tax in Canada?

While much of the talk of imposing a wealth tax is emanating from the U.S., the dialogue has made its way north. In the fall election, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh promoted the idea of a wealth tax on those worth more than $20 million, which it said would generate as much as $6.8 billion by 2023. And the Liberal party, which has legislated increases on tax rates for the maknig $200,000 or more, made tepid advances toward taxing overt consumption, calling for a “luxury tax” on point-of-sale purchases for cars, boats and aircraft valued at $100,000 or more.

David Macdonald, a senior economist for the Canadian Centre of Policy Alternatives, has noted that “language of inequality” began to get vociferous globally after the Great Recession of 2008-2009. People were outraged when they saw big banks, which made obscene amounts of money through questionable practices causing the meltdown, being bailed out by governments around the world without being punished. “That raised the profile of income inequality in that a different set of rules existed for the most wealthy compared to regular Canadians,” says Macdonald.

Macdonald says that the divide between the rich and poor is particularly evident in Canada. “At present, we have a high concentration of wealth in very few people’s hands,” he says. “The wealthiest 87 families have more wealth than the bottom 12 million Canadians combined.” To put that in perspective, Macdonald estimates that these 87 families — the Thomsons, Westons, Rogers and Irvings, to name just a few — have the same wealth as all the people living in P.E.I., New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador combined.

And the rich, as they say, just keep getting richer because of preferential treatment by the tax system. According to Macdonald, this wealth is staying in families and growing, something he calls “an intergenerational concentration of wealth.” So instead of an individual working hard to build a business and reap its profits, “more of these rich families are just inheriting their wealth from previous generations.” And these super-wealthy families maintain their fortunes through preferential tax breaks, which their accountants are paid vast sums to exploit.

Historically, we have taxed income (the amount someone makes per year) but not wealth. But as governments look for new revenue to pay for critical and high-cost programs — such as a national pharmacare plan — it seems that a wealth tax is all but inevitable.

“There’s certainly money to be made here, and the burden would fall on very few families,” says Macdonald, who calculates that the NDP wealth tax would hit only about 6,000 of the 15.3 million families in Canada. However, he isn’t convinced the Liberals are willing to go that route.

More likely than a direct wealth tax as is being proposed in the U.S., Macdonald predicts it’s more likely we’ll update our current tax system to close “what are essentially loopholes” in tax system to erase benefits like stock option deductions or capital gains inclusion rate.

Another alternative is to impose an inheritance tax. Canada, unlike other G-7 countries, currently doesn’t have one. Although public polling shows public distaste for an inheritance tax, Macdonald believes that if was structured so that the inheritance tax would only kick in on estates worth more than $5 million, most people would be excluded.

Macdonald notes that the real danger with either wealth or inheritance tax is that they must be bullet-proof. “You have to be committed to structuring them well so people can’t just avoid them, and updating them frequently as the lawyers for the wealthy try to find new ways to avoid them.”