Are Biden and Trump Too Old To Be President? Take a Scientific Look at the Effects of an Aging Brain on Older Politicians

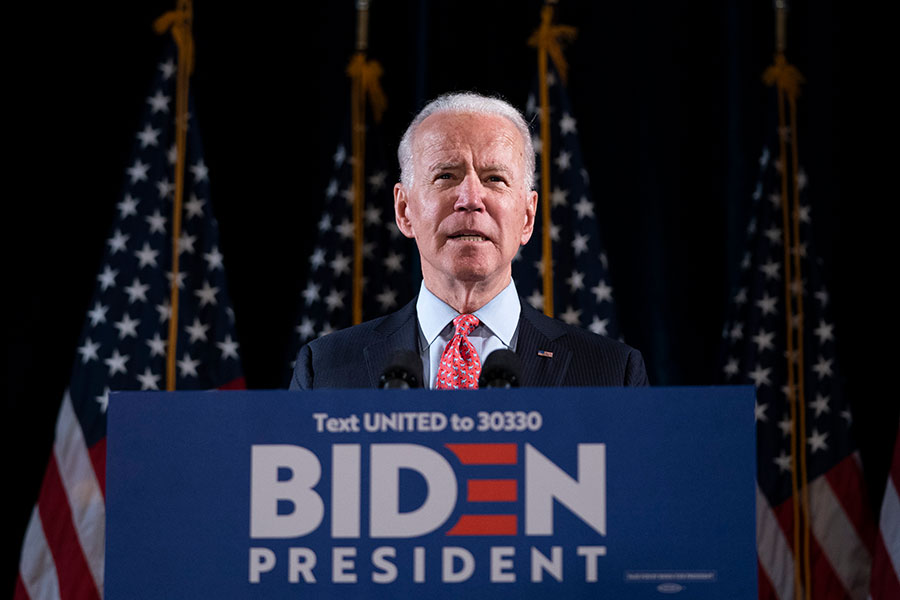

With another election cycle ramping up in the U.S., the debate over the age of the likely candidates is taking centre stage again. Photo: Trump: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images Biden: Photo: Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images

Joe Biden’s age and cognitive abilities have become a political flashpoint thanks to controversial comments made by a special counsel who was looking into the case of the president’s mishandling of classified documents.

On Feb. 5, special counsel Robert Hur released a 345-page report, most of it advising that Biden should not be held criminally responsible for storing classified documents dating back to the time when he left office as vice president in 2016.

This exoneration should have been a victory for Biden. However, in making his report, Hur saw fit to comment on the 81-year-old president’s cognitive faculties. Noting that the president was often confused during questioning, Hur described Biden as a “well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory” who was experiencing “diminished faculties in advancing age.”

These comments set off a powder keg of media commentary, spin and damage control in Washington, handing the Republicans a gift-wrapped opportunity to slam the president. Donald Trump, Biden’s likely opponent in the next election, immediately issued a statement saying that the Democrat leader was “too senile to be president.”

In a televised press conference on Feb. 8, a very angry Biden fired back at Hur, accusing the special counsel of indulging in “extraneous commentary” that had “no place in this report.”

“I know there’s some attention paid to some language in the report about my recollection of events,” said Biden at his press conference. “There’s even a reference that I don’t remember when my son died. How in the hell dare he raise that.”

The president argued that any mix-ups in his testimony were due to the fact that he had “sat five hours of interviews over two days of events, going back 40 years.” Biden’s press secretary, Karine Jean-Pierre, further tried to defuse the special counsel’s comments, saying that Hur is “a Republican … a prosecutor. He’s not a medical doctor.”

Politically motivated or not, Hur’s comments align with a recent poll showing that 86 per cent of Americans, including 73 per cent of Democrats, think Biden is too old run again. The same poll showed that 62 per cent felt that Trump, 78, was too old as well.

Regardless of Biden’s accomplishments in office or the energy level he brings to the job, it’s inarguable that he seems elderly, at least more elderly than Trump. Perhaps that’s why the president’s age has become more of a liability than Trump’s.

He does forget events and names: he recently confused French President Emmanuel Macron with François Mitterrand (who died in 1996) and mixed up the names of the Mexican and Egyptian presidents. Or that he slurs his words and often stumbles when he’s out in public.

Trump presents a certain vivacity that Biden lacks. But the Republican contender is just as prone to memory fails: he recently suggested he defeated Barack Obama in 2016 election, rather than Hillary Clinton, and has mixed up Nikki Haley with Nancy Pelosi. Despite the fact that he also rambles, mumbles and says things that are so lacking in lucidity, it doesn’t seem to touch off any debate about possible age-related cognitive decline – they’re so baked into his public persona that no one even bats an eye.

The question as to whether Trump’s and Biden’s faulty memories make them unfit for to run for office is all but moot – unless the current political situation changes drastically, these two will be vying for the presidency in November.

Dr. Charan Ranganath, a neuroscientist, wrote a guest essay in the New York Times suggesting that the media focusses far too much on Biden’s memory lapses and not enough on the his accomplishments over his term in office.

“There is forgetting and there is Forgetting,” he writes. When Biden forgets dates and names it’s more due to what Ranganath calls “retrieval failure” – when know the word or name but we just can’t “pull it up when we need it.” Biden, he writes, is not suffering from “Forgetting” (with a capital F) – when the memory is “lost or gone altogether.

“Ultimately, we are due for a national conversation about what we should expect in terms of the cognitive and emotional health of our leaders. And that should be informed by science, not politics,” Ranganath concludes.

To help inform this debate we revisit an article that was published leading up to the 2020 U.S. election, in which Carolyn Abraham takes a deep dive into the latest science of aging brains and whether natural cognitive decline should preclude older candidates from running for office.

Election on the Brain

By Carolyn Abraham

Presiding over the United States may be the world’s most powerful job, but the workload is hell. George Washington complained, Woodrow Wilson called it “preposterous” and, after President Barack Obama took office, his hair turned grey before he turned 50. In 2009, a provocative study suggested that a stint in the White House is such a pressure cooker that it can age presidents at twice the speed of other mortals. So what might the velocity be in times like these?

A global pandemic is upending the world order. The virus behind it is killing more people in the U.S. than in any other developed country. Some 30 million people are jobless, the U.S. economy is sputtering and protests for racial justice are forcing a reckoning across the country, erupting into deadly clashes between left and right, Black and white.

Whoever takes the helm in 2021 faces a task beyond daunting, a 24-7, ultra-demanding challenge of Herculean proportions. Of course, a Roman god is not in the running. The choice is down to two septuagenarian men – the oldest presidential candidates in U.S. history – and fears abound that neither one has the stamina nor mental fitness for the job.

Never has the aging brain been such a pressing issue on the ballot – and with good reason. Neuro-imaging studies increasingly show that time is a vandal, destroying the brain in random bits and pieces. But research also finds that mental deterioration is not inevitable, that some brains do age better than others. What American voters will have to decide on Nov. 3 is which candidate has staved off cognitive decline enough to run the country.

Is it former Vice-President Joseph R. Biden Jr., the 77-year-old Democrat who underwent surgery for two cerebral aneurysms in 1988, a self-described “gaffe machine” who has mixed up which state he was in – repeatedly – and, during his Super Tuesday victory speech in March, mistook his wife for his sister?

Or is it the 74-year-old incumbent, President Donald J. Trump, a self-described “stable genius” who wondered if injecting the body with disinfectant could beat COVID-19, who peddles the conspiracy theories of others and his own, who has bragged about the size of his “nuclear button,” a nuclear weapon system he was supposed to keep secret, “acing” a dementia test and, according to the Fact Checker database of the Washington Post, has lied more than 20,000 times since taking office? Most notably is Trump’s own admission that, from the earliest days of the pandemic, he has deliberately misled the American public about the severity of the novel coronavirus when he understood it to be an airborne killer.

An army of mental health experts – including Trump’s niece – believe the president’s erratic behaviour is not so much a symptom of an aging brain as an ailing one, describing his vindictive narcissism as the hallmark of a personality disorder. Mary Trump, a clinical psychologist, writes in her new book, Too Much and Never Enough, that her uncle’s “pathologies are so complex and his behaviors so often inexplicable that coming up with an accurate and comprehensive diagnosis would require a full battery of psychological and neuro-physical tests, that he’ll never sit for.”

The U.S. military bars people with most psychiatric disorders from serving in its ranks, and an estimated 80 per cent of Fortune 100 companies require high-level job candidates to undergo psychological tests. Yet those vying to be commander-in-chief of a country of more than 330 million citizens and the U.S. Armed Forces, the most powerful military on the planet, face no such assessments – a fact that brain experts both in and outside the U.S. lament.

“They should go through a lot of psychological testing if they are going to be responsible for the nuclear bomb and responsible for many important decisions and be the head of the army,” says Dr. Zaid Nasreddine, the Canadian neurologist who designed the dementia-screening test Trump says he “aced.”

Nasreddine developed the 10-minute 30-question exam in the ’90s as a time-saver to detect cognitive impairment when he was a young doctor eager to see more patients in a day. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or the MoCA, which includes tasks that evaluate memory, executive function and verbal fluency, is now used in 65 languages and more than 200 countries. Still, Nasreddine says, “not in my wildest dreams” did he imagine a U.S. president would wield it as proof he’s mentally fit for his job and as a challenge to Biden to beat his score.

WATCH: President Trump challenges Joe Biden to take cognitive test

“[Trump] is turning it into an IQ test, which is not the purpose of the test,” says Nasreddine. “It’s not to measure how skilled you are but to measure if you have any cognitive disorder.”

Usually, he explained, the test is given to suss out Alzheimer’s or dementia in older adults showing signs of mild cognitive impairment, such as forgetfulness, or to those who have suffered a stroke, concussion or other brain injury. But former White House physician Dr. Ronny Jackson said the president insisted he take such a test in 2018, when critics were voicing concerns over his mental fitness and, this summer, Trump has said repeatedly his “amazing” results prove he is “cognitively there.”

Yet as Nasreddine and other experts note, the exam is not designed to pick up all mental health and psychiatric issues or the decline in reasoning that can become more common later in life.

As it is, the voters’ best chance to assess the cognitive state of the candidates may come with the three presidential debates scheduled for the final weeks of the campaign.

“How the candidates handle themselves in the spontaneity of debates tells you a lot about how they are functioning cognitively,” says Dr. Mark Fisher, a neurologist and professor of political science at the University of California at Irvine. They offer viewers an opportunity “to look for focused, coherent answers as indicators of good cognitive function.”

A Sobering View

Then the Founding Fathers signed the American Constitution in 1787, their only age-related concern was that some candidates would be too young for public service, so they set minimum requirements: 25 to be a representative; 30 to be a senator; and 35 for president. It never occurred to them to set a maximum, since life expectancy at the time was 38.

But the expected lifespan of a human has risen 40 years since then and, with it, the belief and confidence that advanced age should be no barrier to any realm of human endeavour, whether it’s running a marathon or running for office. Unfortunately, the bravado generally outstrips the realities of brain biology.

Using ever more sensitive neuroimaging techniques, scientists peering inside the aging brain usually find the view is sobering. The three-pound marvel that houses the human mind, with its capacity to store the equivalent of every movie ever made in a cubic millimetre of tissue, shrinks significantly between the ages of 40 and 80, losing neurons and the crucial links between them. What researchers see is an organ damaged by the chronic conditions that tend to develop as people age, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, Type 2 diabetes and obesity.

“All these conditions affect how well our brains are fed nutrients and vascularized,” says Teresa Liu-Ambrose, the Canada Research Chair in physical activity, aging and cognitive neuroscience at the University of British Columbia. “We start seeing deficits in the small vessels that feed deep into the brain, so you don’t have a stroke – as when a major vein or artery is compromised – but you have localized death of the brain tissue … [which] affects how your brain activates and functions.”

As specific brain areas atrophy, microbleeds starve the brain’s crucial white matter, the fatty sheaths that coat nerve fibres to speed connections between brain cells. Liu-Ambrose likens white matter to “the highways and roadways of a city” that enable one area of the brain to speak quickly to another, and losing it, she says, “is like blowing up a roadway.”

These micro-insults to the brain can start accumulating when people are still in their 40s, she says, forcing the older brain to function differently. For example, “when young people do a task, the activation patterns are typically very constrained to a certain area that’s known to play a part in the performance of that task. With older adults, we tend to see a diffuse activation pattern where it seems like the brain is trying to recruit additional areas to allow the performance.”

Sometimes the recruitment effort pays off, and researchers find an older adult can perform just as well as a younger one, if not better, on certain cognitive tasks.

But when it doesn’t, it can lead to memory slips and cognitive deficits, particularly in executive function – setting goals, planning, organizing, controlling impulses and making sound decisions. Executive function is the highly evolved capacity that stems from the prefrontal cortex directly behind the forehead and, to work well, it relies on strong connections to other brain regions – links that vascular damage can disrupt.

Still, experts agree cognitive deterioration is not everyone’s destiny. Like faces, brains are similar, but no two are identical, and how they function over time also depends on education, experience, exercise and mental activity. Liu-Ambrose points out while some brains decline when people are in their 50s and 60s, others stay sharp into their 80s. “That’s why there is so much focus now on your vascular health because what’s good for your heart is good for your brain.”

“The Healthiest Individual Ever”

Medical exams, like psychological assessments, are not legally required of presidential candidates. But traditionally most offer doctors’ reports vouching for their general fitness to do the job. In the case of both Biden and Trump, there’s evidence their vascular health is imperfect.

The summary from Biden’s doctor, released last December, says the former senator from Delaware has an irregular heartbeat, takes an anticoagulant to reduce his chances of developing blood clots and a statin drug to control his blood lipid levels. But it also notes CT scans show no recurrence of the cerebral aneurysms he had surgically repaired in 1988.

Psychology professor Angela Gutchess, who specializes in aging brain research at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., suspects Biden’s aneurysms were the result of “an underlying structural deficit rather than reflecting cardiovascular health … the fact that [they developed] so long ago, and they’re not linked with age-related conditions, make them seem like less of a concern.”

Indeed, Biden has balked at Trump’s relentless attacks suggesting that he’s the “sleepy candidate” on the road to senility and has refused to be baited by the president’s taunts to take a cognitive test – “Why the hell would I?” he told CBS. During an interview with ABC anchor David Muir in late August, Biden said he’s not only fit to do the job but fit enough to serve two terms and that his behaviour speaks for itself: “Watch me, Mr. President, watch me … Look at us both, what we say, what we do, what we control, what we know, what kind of shape we’re in.”

Watch a clip of Joe Biden’s ABC interview below

Biden’s medical report includes other positive points related to his heart health – he has no history of high blood pressure, tobacco use or diabetes, no issues with his weight and works out five times a week.

Meanwhile, beyond golfing, Trump is not a fan of exercise. In their book Trump Revealed, Washington Post reporters Mike Kranisch and Marc Fisher say the president gave up athletic pursuits after college, believing the human body is “like a battery, with a finite amount of energy, which exercise only depleted.”

For the most part, the president’s medical reports have been nearly as elusive as his tax returns. The doctor’s letter he offered the public before the 2016 election turned out to have been dictated to the physician by Trump himself and attested to his “astonishingly excellent” blood pressure and proclaimed he would be “the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency.”

Since then, the limited health information about Trump has fuelled speculation that the president has something to hide, particularly after he made an unscheduled visit to the Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., last November. Conjecture spiked again in June after Trump gave the commencement address at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he appeared to have difficulty raising a water glass to his mouth and used both hands and then looked apprehensive and unsteady as he walked gingerly down the stage ramp.

Trump has vociferously dismissed the concerns that followed his West Point address, and the White House has insisted the mysterious Walter Reed visit was routine.

But in his new book, Donald Trump v. The United States, New York Times reporter Michael S. Schmidt writes that during Trump’s impromptu hospital visit last fall, “Word went out in the West Wing for the vice-president [Mike Pence] to be on standby to take over the powers of the presidency temporarily if Trump had to undergo a procedure that would have required him to be anesthetized.”

In response to the book and the coverage it unleashed, Trump – who had lost his balance on another stage ramp at the New Hampshire rally – tweeted: “Now they are trying to say that your favorite President, me, went to Walter Reed Medical Center, having suffered a series of mini-strokes. Never happened to THIS candidate – FAKE NEWS …”

Yet neither Schmidt’s book nor other media reports had mentioned anything about the president suffering from mini-strokes. Still, Trump had his physician, Dr. Sean Conley, take the extraordinary step of sending out an official statement that the president had not experienced or been evaluated for a stroke, mini-stroke or heart-related emergencies.

All that has been publicly released about Trump’s medical details came with a report in June that says the president’s annual physical indicates his overall health is good; he has no high blood pressure, history of tobacco or alcohol use and no diabetes. He reportedly takes the hair-growth drug Propecia to fight baldness, a medication to treat a common skin condition called rosacea and a statin drug to keep his high cholesterol in check. His weight is the only red flag. Trump, a lover of fast food, is obese.

But to neurologist Fisher, there’s something missing from Trump’s medical report that he’s noticed for years as a cause for concern – the circumference of the president’s neck. “Remember this is a man in his early 70s. He’s overweight, he’s clinically obese and, if you look at his physique, he has a thick neck.

“If you want to identify the kind of person who is at highest risk of obstructive sleep apnea, it would be an obese man in his 70s with a thick neck, and that matches up pretty well to President Trump. I don’t know if he’s ever had a sleep study, but that would be an area that deserves attention.”

Obstructive sleep apnea occurs when throat muscles intermittently relax and narrow the airway, causing breathing to repeatedly stop and start during sleep. The effect, says Fisher, “can certainly contribute to cognitive decline and it can certainly contribute to subtle neuropsychological disturbances, and we would expect that executive function would certainly be impacted.”

Executive Dysfunction

In 2014, after images of the aging brain’s deterioration had stacked up, Fisher penned a report warning its findings have troubling implications for the political world, since it was becoming increasingly common to see candidates for president and vice-presidents in their 60s and 70s.

Under the title “Executive Dysfunction, Brain Aging and Political Leadership,” Fisher and two other colleagues wrote in the journal Politics and The Life Sciences that “we should probably assume that a significant portion of political leaders over the age of 65 have impairment of executive function.” Most, worrisome, he says, is that it can affect how people make decisions – arguably a leader’s most crucial responsibility.

“Under the surface of what appears to be normal behaviour,” says Fisher, “there can be stuff going on that is of concern and has substantial ramifications in the public arena and the political arena.”

History certainly offers its share of examples. President Woodrow Wilson, widely known for his rigidity, self-righteousness, womanizing and bigotry, quietly suffered from cerebrovascular disease. The extent became apparent after the First World War’s Paris Peace Talks in 1919, when Wilson, then 63, had a massive stroke. Several reports suggest two-term President Ronald Reagan had also shown signs of cognitive impairment and in 1994, five years after he left the White House, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

At 69, Reagan had been the oldest person ever to be sworn in as president until the election of Trump, who was 70. Biden, who turns 78 on Nov. 20, will beat that record should he win the Nov. 3 election and be inaugurated in January 2021.

Reagan, the former Hollywood actor, remains the oldest outgoing president, leaving office when he was nearly 78.

In advanced years, executive dysfunction may not always be obvious, but it can manifest itself in bewildering decisions “that don’t really add up,” says Fisher and “decisions that would seem to be out of character, given an individual’s track record.” Some of these signs he sees in Trump.

“Some of the decisions he’s made during this current year – some of them have been head-scratching … in terms of handling the pandemic, the inconsistencies of his comments and the refusal to establish a clear centralized approach to the pandemic. One could argue that this is really indicative of executive dysfunction in the chief executive.”

Indeed, pundits and historians will likely spend years dissecting Trump’s tragic and deliberate decision to downplay the severity of COVID-19 to the American people. In taped interviews Trump gave to investigative journalist Bob Woodward for his upcoming book, Rage, the president can be heard saying on Feb. 7 that he believed the virus was “deadly stuff” far worse than the flu, and highly contagious. Meanwhile, in public he was calling it a Democratic “hoax.” He likened it to the seasonal flu, balked at mask wearing and business closures. Trump told Woodward he always likes to downplay it so people won’t “panic” – even as the virus spread like wildfire and was killing an average of 1,000 Americans a day.

Trump also made the puzzling decision to reveal a state secret to Woodward, telling the legendary Watergate journalist that he had overseen the creation of a new nuclear weapon system that would surprise even Russia and China – a disclosure that reportedly surprised the president’s military.

If Trump’s decisions are bewildering, they can also be rigid. Fisher has noticed, for example, the president has a “lack of flexibility in decision-making, perhaps an incapacity to say to himself, ‘Look, these kinds of attitudes might have worked a year or two ago, but things have changed, the situation has changed – medically with the pandemic and on the street, with the political views in the country,’ and that is suggestive of something more problematic than just political miscalculation.”

On the other hand, he notes that Biden has shown that he is

capable of making “an excellent choice on a critical issue, selecting [California Senator] Kamala Harris for the vice-presidency. This is good executive function.”

Buffers

By choosing Harris as his running mate, most observers feel Biden not only boosted the brain power of his potential administration, he infused it with the generational currency it needed. Harris is a 55-year-old former prosecutor and attorney general known for her smarts, verve and charisma. She is a first-generation American born to an Indian mother and Jamaican father and the first woman of colour to be nominated for the post at a time when racial diversity among the country’s leadership has never mattered more.

During the Democratic primaries, Harris attacked Biden for his voting record on a 1970s desegregation issue, so the forgive-and-forget nomination as his running mate signals Biden’s shrewd political calculation.” Harris brings a new coalition to the table – the Carribean and South Asian diaspora, women and, in particular, Black women, the key voting bloc of the Democratic Party. Her law enforcement background counters Trump’s latest attacks that Biden is soft on crime.

A leader at risk of cognitive decline benefits from having the right advisers, says Brandeis psychologist Gutchess. “I think it’s one of the things that often buffers this issue of cognitive decline,” she says, “which is why all the turnover in the Trump administration gives some cause for alarm … [it] suggests [Trump] is not able to use the good advice he’s getting at times, but this gets into personality aspects, beyond cognition.”

According to the Washington, D.C.-based Brookings Institution, a non-profit, public-policy think-tank, Trump boasts a senior staff turnover rate of 88 per cent – higher than every other president since Ronald Reagan. He’s on his fourth chief of staff, fourth national security adviser and fourth press secretary. He has also burned through five communications directors.

Many of the break-ups have been public and ugly, culminating in a litany of name-calling tweets from Trump – dubbing his former Attorney General Jeff Sessions “Mr. Magoo” and his former National Security adviser John Bolton a “low-life dummy.”

In his scathing June 2020 memoir, The Room Where It Happened, Bolton painted the president as impulsive and ill-informed, saying Trump lacks the attention span to sit through briefings, which devolved from written summaries to visual aids. The 2019 book A Warning by an anonymous White House adviser likened Trump to a havoc-wreaking old man in a nursing home “running pantsless across the courtyard and cursing loudly about the cafeteria food, as worried attendants tried to catch him.”

Experts tend to agree that a psychiatric disorder – if one exists – would likely exacerbate any cognitive decline due to aging. As a rule, says Fisher, “If you have any kind of pre-existing condition, brain aging and deteriorating cognitive function, that’s going to be more pronounced.”

Tweet, Tweet

Nothing raises more concern about the president’s mental state than his Twitter feed. A stream of consciousness that flows relentlessly to his 85 million followers, Trump’s tweets are a heady mix of boasts, threats, insults and indignation, often in all caps, at all hours, with a personal record this summer of 74 tweets within one hour.

Yet his posts routinely trigger not just controversy but alarm. Last October, for instance, the president tweeted: “As I have stated strongly before, and just to reiterate, if Turkey does anything that I, in my great and unmatched wisdom, consider to be off limits, I will totally destroy and obliterate the Economy of Turkey (I’ve done before!) … “

In response, Harvard University psychology professor Daniel Gilbert tweeted that the president’s comment might be grounds for involuntary detention under psychiatric care. “Am I the only psychologist who finds this claim and this threat truly alarming? Wouldn’t these normally trigger a mental health hold?”

Gilbert certainly is not alone. But the Goldwater Rule of the American Psychiatric Association prevents mental health experts from offering a frank assessment of Trump’s mindset. Created in 1973, the rule stems from the controversial armchair comments that psychiatrists made about the mental health of 1964 presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. As a result, the APA code of conduct deems it unethical for psychiatrists to offer a professional opinion on public figures that they have not personally examined. But 37 psychiatrists and mental health experts have since gone rogue, arguing that Trump’s own Twitter feed and more than three decades of his public commentary and media interviews provided enough information to justify voicing their opinion. In The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, an essay collection first released in 2017, the authors say they felt a moral duty to warn society that the president’s mental instability – specifically his “narcissistic rage” – puts the country at risk.

A group called Duty to Warn, founded in 2017 by Baltimore psychologist Dr. John Gartner, a former assistant professor at Johns Hopkins medical school who specializes in borderline personality disorders, gathered nearly 60,000 signatures on a petition calling for Trump’s removal from office due to “serious mental illness.” In 2018, an anonymous White House source claimed to be working with other Trump advisers who had contemplated invoking a provision in the constitution’s 25th Amendment, which covers succession procedures involved in presidential disability, to have Congress declare the president “incapacitated.”

But that same year, White House doctor Jackson, a retired Navy rear admiral who has called Trump a “close friend” and Obama a “deep-state traitor,” reported the president has “absolutely no cognitive or mental issues whatsoever” and that Trump had scored a perfect 30 out of 30 on the MoCA test.

For many skeptics, in the press and online, the 2018 report from Jackson – who is now a Trump-endorsed Republican candidate for Congress in Texas – was hard to swallow. They accused Jackson of lying, suggesting that the doctor had underreported Trump’s weight at 239 pounds, and overplayed his cognitive test results.

Nasreddine, who heard about Trump’s MoCA result from a White House reporter in 2018, says a perfect score is impressive for a man of the president’s age, that it’s a feat only 10 per cent of 73-year-olds achieve.

It is unclear if the president took the test again more recently but,

after speculation swirled around his health in June, Trump began mentioning a cognitive test he “aced” in July and referred to tasks found on the MoCA, such as recalling five words in order.

Critics have likened Trump’s comments to bragging about being able to tie your shoes since the test includes questions that ask people to name the date, identify animals by their silhouettes and to connect dots between numbers and letters.

And Fisher notes that performance can get better with practice. “If you understand that your score on the MoCA is going to have ramifications outside of the doctor’s office, it’s not at all difficult to prepare for it and to improve your score.”

What’s in a Word?

Beyond the thousands of written words contained in Trump’s tweets, the spoken words of both presidential candidates may offer insights into their cognition.

“It’s fair to say that our ability to express ourselves, the words we choose and the way we say them and the range of vocabulary does reflect our level of intellect and/or our level of decline with a cognitive disorder,” says Montreal neurologist Nasreddine.

Both Biden and Trump are notorious for their awkward dance with the English language, but Nasreddine says, “Many people will have these same symptoms [of misspeaking] but will not necessarily move on to a more degenerative disorder.”

In Trump’s case, more than one analysis has weighed in on his tortured syntax, incomplete sentences and tendency to veer off topic. In 2018, a machine-learning study from Factba.se, a privately owned online archive of all the president’s publicly spoken and written words, found Trump’s grammatical structures and limited vocabulary (“tremendous,” “huge,” “incredible”) pegged his general discourse to be at a fourth-grade level, the lowest of the last 15 U.S. presidents.

Biden, meanwhile, has had a lifelong struggle with words. Growing up with a stutter, he faced schoolyard taunts, bullies and often embarrassment. He overcame it by reading poetry and practising speeches in front of mirrors, but Biden has said that even now, fatigue and stress can trigger its re-emergence.

Stuttering is believed to have genetic roots, but it’s unclear if the speech disorder contributes to Biden’s long history of misstatements. Yet as their frequency seems to be increasing, many pundits and critics see the bloopers as worrisome signs of a brain on the wane. Some – “Poor kids are just as bright and just as talented as white kids” – send Biden’s handlers scrambling to issue clarifications; others, however, are received as harmless, even charming – “We choose truth over facts!”

“I am a gaffe machine,” Biden admitted in December when asked about the verbal blunders that could haunt his campaign. “But my God, what a wonderful thing compared to a guy who can’t tell the truth.”

Indeed, fact-checking Trump is a full-time job, employing journalists who do nothing but – and their workload has increased. The Fact Checker team of the Washington Post finds Trump was averaging a dozen fibs a day, but over the last 14 months, the tally jumped to the president telling an average of 23 lies or misleading statements daily.

Among the most common are claims that his administration “built the best economy in U.S. history,” which he has said 360 times and, on 128 occasions, he has said that he’s “done more than any other president in his first three and a half years.” The pandemic has also created a new genre of untruths, such as “the U.S. has the lowest mortality rate in the world” – which he said 13 times. The misleading comments have also become more elaborate in the midst of the summer’s deadly racial unrest, spurring Trump to promote an array of conspiracy theories and his own concoctions to argue that he is the only leader who can save the country.

During a bizarre August interview with Fox News host Laura Ingraham – who tried repeatedly to rein in the president’s wild remarks – Trump alleged that Biden is controlled by “people that are in the dark shadows,” far-left anarchists “who control the streets” and funded by “very stupid rich people.” Before the Republican National Convention, Trump told Ingraham that a plane “loaded with thugs wearing these dark uniforms, black uniforms, with gear” had been on its way to Washington “to do big damage.” The president could offer few other details, but it’s an unsubstantiated story he went on to tell again in the days ahead.

Research from Gutchess’s lab at Brandeis shows that older adults are vulnerable to misremembering things. But, Gutchess says, untruths are more likely to become embedded as false memories if people are motivated to believe them, and they keep repeating them. “I suspect we are seeing both of these things going on with the current [Trump] administration.”

Social scientist Bella DePaulo, who studied the psychology of lying for two decades at the University of Virginia, found Trump’s falsehoods not only dwarf the average of two lies most people tell in a day, but that the president’s lies are dramatically different in substance. In a 2017 report in the Washington Post, she explained most lies are either self-serving in some way or kind lies told to protect the feelings of others. But DePaulo found that 65 per cent of Trump’s lies are self-serving, a figure 6.6 times higher than the average, only 10 per cent are kind, and a remarkable 50 per cent are cruel, told to embarrass or disparage others and, in many cases, can also be categorized as self-serving.

The Price of Experience

Once upon a time, the U.S. was considered the capital of the New World and the American president, the leader of the free world. But recent self-reflections have the rocking-chair creak of a nation past its prime. Last fall, writing in Politico, Timothy Noah called the republic “a wheezy gerontocracy … our leaders, our electorate and our hallowed system of government itself are

extremely old.”

In March, The Atlantic put it bluntly in a piece titled “Why Do Such Elderly People Run America?” Writer Derek Thompson wondered if the aging candidates simply reflect the country’s aging population, that older adults are more likely than young people to vote and to support people close to their own age. But while Europe’s population also skews older, the typical European Union leader has gotten younger.

Practical reasons may explain it in part – older candidates have had more time to line up campaign donors and more time to build experience, which is generally an asset on any job application.

“With age, often what allows people to function really well is experience, expertise and familiarity,” says Gutchess, since procedural and factual knowledge tends to be preserved. “If you’ve been working with politicians for years, you know them and you know how things work.”

Of course, Trump rode to power in 2016 in part because of his outsider status. The real estate mogul and former reality TV star had no political experience but promised to “drain the swamp” that he said was Washington. In contrast, Biden is a career politician, elected to the Senate when he was 29, a position he held for 36 years before serving as Obama’s vice-president for eight years.

Considering what science now tells us about the aging brain, it seems some cognitive decline is nearly inescapable among those over 70, and the Trump-Biden showdown has prompted more than one observer to call for a maximum age limit for the presidency. Others have called for a review of the office itself, restructuring the presidency to reduce its workload. But for now, voters will have to exercise their own executive function to decide for themselves which candidate – Biden or Trump – has the best advisory team, the strongest track record and enough power of heart and brain to heal a nation ravaged by plague and riven from within.

A version of this article appeared in the Nov/Dec 2020 issue with the headline, “Election on the Brain,” p. 53.

RELATED:

Demographic Deficit: Has the Rise of Older Politicians Forced Millennials to the Sidelines?

Biden, 80, Makes 2024 Presidential Run Official Amid Concerns About His Age