A Vaccine for Alzheimer’s?

Is it possible that, sometime in the future, children carrying a high-risk gene for Alzheimer’s could receive a vaccine to prevent the disease, in the same way kids now are immunized against diphtheria, whooping cough, measles and polio?

Two new reports suggest this possibility shouldn’t be consigned to the category of science fiction.

An Alzheimer’s risk gene may begin to affect brains as early as childhood, say researchers at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

People who carry a high-risk gene for Alzheimer’s disease show changes in their brains beginning in childhood, decades before the illness appears.

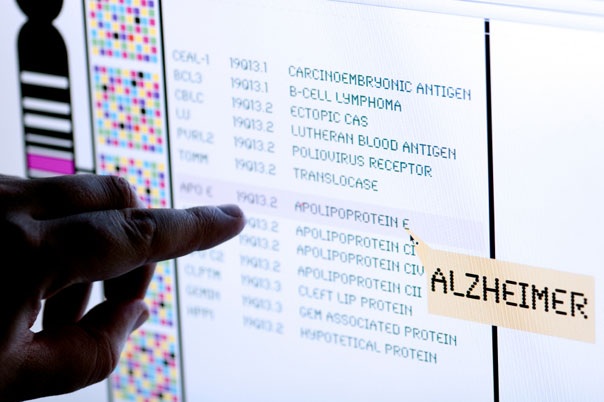

The gene, called SORL1, is one of a number of genes linked to an increased risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of the illness.

SORL1 carries the gene code for the sortilin-like receptor, which is involved in recycling some molecules in the brain before they develop into beta-amyloid, a toxic Alzheimer protein.

“We need to understand where, when and how these Alzheimer’s risk genes affect the brain, by studying the biological pathways through which they work,” says Dr. Aristotle Voineskos, who led the study. “Through this knowledge, we can begin to design interventions at the right time, for the right people.”

In fact, there’s good news today about an intervention that may work to prevent Alzheimer’s (and not just with healthy lifestyle habits, which is the best prevention we have so far.)

Scientists are “full of hope” that a breakthrough in drug therapy to prevent dementia could come within five years, Dr. Eric Karran, director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, told the London Telegraph.

While the drug has been tested in very early trials, positive results from further trials could mean that people with a family history of dementia are given monthly injections of the drug a decade before any signs of disease show – in the same way that millions of people now take statins to ward off heart disease, Dr. Kerran told the Telegraph.

He was speaking ahead of a G8 summit next week on dementia.

The drug, called solamezumab, may delay the onset of disease, has shown to be more successful in those with mild dementia, with an effect on daily behaviour and the functioning of their brain and memory. But it failed to show effective results in people with moderate dementia.

The CAMH study, carried out in collaboration with researchers in New York and Chicago, was published online in Molecular Psychiatry.

To understand SORL1’s effects across the lifespan, the researchers studied individuals both with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Their approach was to identify genetic differences in SORL1, and see if there was a link to Alzheimer’s-related changes in the brain, using imaging as well as post-mortem tissue analysis.

In each approach, a link was confirmed.

In the first group of healthy individuals, aged eight to 86, even among the youngest participants in the study, those with a specific copy of SORL1 showed a reduction in white matter connections in the brain important for memory performance and executive function.

The second sample included post-mortem brain tissue from 189 individuals less than a year old to 92 years, without Alzheimer’s disease. Among those with that same copy of the SORL1 gene, the brain tissue showed a disruption in the process by which the gene translated its code to become the sortilin-like receptor.

Finally, the third set of post-mortem brains came from 710 individuals, aged 66 to 108, of whom the majority had mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s. In this case, the SORL1 risk gene was linked with the presence of amyloid-beta, a protein found in Alzheimer’s disease.