Parkinson’s: Brain Reinterpreted

A world leader in neurology is developing breakthroughs for those living with Parkinson’s disease. JULIE ENFIELD reports.

It was a blazing hot august morning, not a cloud in the sky. Katherine Hays (not her real name), a 51-year-old college teacher in Oakville, Ont., was preparing notes for her fall term exam when she noticed a mild tremor in her right hand. Initially, she thought it was just one of those annoying twitches, the kind that go on for a few days. But it didn’t go away. Six months later, her right arm started to tremble, and she got worried. An emergency room intern at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto chalked up Hays’s condition to “something neurological.” Then, after a shocking series of brain exams, a staff neurologist made an on-the-spot diagnosis: Parkinson’s.

“I was stunned,” recalls Hays upon learning that she had a neurodegenerative disease. “I literally shook my fist at the messenger who had delivered the dire news – and began to sob.” With her mind still spinning in disbelief, Hays managed to ask the doctor, “Is there a cure?” No, there wasn’t. “It was the darkest moment of my life,” she says, adding, “I remember thinking that my destiny had nothing to do with the cracked vinyl hospital chair where I found myself sitting, railing against phrases like ‘progressive brain disease’ and ‘lifetime of medication.’ ” Indeed, it was light-years away from the early retirement that Hays had planned.

When Hays left the hospital, it was almost dusk. She looked up into the winter sky, an empty grey. And the impact of those three words – “You have Parkinson’s” – remained frozen in her brain like leaves imprisoned in ice.

SUPPORT RAPPORT

If this all sounds like a scene from Misery, Joyce Gordon, president and CEO of the Parkinson Society of Canada, insists that it isn’t. Gordon maintains that the sooner you come to terms with the diagnosis and begin treatment, the less rapidly the physical and emotional challenges are likely to progress. Although symptoms can vary from person to person, the most common physical manifestations include trembling in the hands, arms, legs, jaw and face; slowness of movement; and problems with balance and co-ordination. Increasingly, the early non-motor features of the disorder are becoming recognized, including emotional symptoms such as anxiety and depression as well as pain and other sensory complaints.

Gordon also believes great advances are being made in understanding the causes of progressive neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and that new studies such as the leading-edge research that is currently being done at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre at Toronto Western Hospital (TWH) will result in better treatments for patients like Hays and the 100,000 Canadians who suffer with Parkinson’s, which typically manifests after age 50.

FEAR FACTOR

When Hays stepped off the seventh-floor elevator into the Morton and Gloria Schulman Movement Disorders Clinic at TWH, she allowed herself a small ray of hope. She had lived with fear since she had been diagnosed a year earlier. “Waking up each morning, knowing that you have to cope with the daily challenges of a progressive neurological disease for which there is no cure can be pretty daunting,” admits Hays, adding, “Even the process of finding the right medications and developing an effective timetable [for Hays, it’s three times a day] is enough to set off an avalanche of anxiety.”

“Fear – at least, this kind of fear – is not something that you experience and then you just leave it behind,” she explains. “It’s always there. It persists.” Her dread of not being able to write notes on the chalkboard soon became a reality. To Hays’ horror, her right arm would freeze up as soon as she entered the classroom.

“I became severely depressed and would set my alarm clock at 3 a.m. in order to train my left hand to do the task,” she says. But it didn’t stop there. She recalls feeling paralyzed with fear at the mere thought of attending a faculty meeting. “I couldn’t apply mascara, style my hair or even button up my jacket because I had limited mobility in my right hand.” It got to a point that Hays’ social calendar was redacted with cancellations. “It was a dark moment and I only had my family and a few close friends for support,” she says. “I didn’t want anybody to feel sorry for me.”

Hays took a seat in the waiting room of the Movement Disorders Clinic, where everything was about to change.

CAUSE CEREBRAL

Dr. Anthony Lang may be the closest Canada has to an authentic mentalist. At 62, he exudes a reassuring confidence, with penetrating blue-grey eyes and a boyishly lean build. A professor and director of the division of neurology at the University of Toronto and the Jack Clark Chair for Parkinson’s Disease Research at that university as well as director of the Edmond J. Safra Program in Parkinson’s Disease at TWH’s Krembil Neuroscience Centre, he speaks with almost alarming frankness, discussing the nuances of the brain the way most people talk about Ikea furniture – after it has been assembled.

“By accident, as most great discoveries happen” is how the Toronto-born world leader in Parkinson’s research describes his introduction to neuroscience. Lang, the eldest of eight children, had his career charted out as a cardiologist during his residency at the University of Toronto in 1975. But all it took was one serendipitous weekend on call in neurology at St. Michael’s Hospital to shift his career path. And, as fate would have it, head won over heart. “I enjoy the science. I quickly realized that neurology presented some very interesting challenges,” he explains. Then, he adds, “Neurology is the last medical frontier.” But ask Hays or any one of Lang’s thousands of patients what it is specifically that this “brainiac” carries around in his medicine bag that separates him from most others in his field, and they would probably all agree: compassion. “I cherish being able to have a good interaction with patients and have an influence on their lives in a positive way,” says the charismatic doctor, leaning forward, his elbows on his knees. “I’m full time. I love what I do.” Case in point: there isn’t a single patient profile at the Movement Disorders Clinic that doesn’t have his fingerprints on it.

BEYOND “DIAGNOSE/ADIOS”

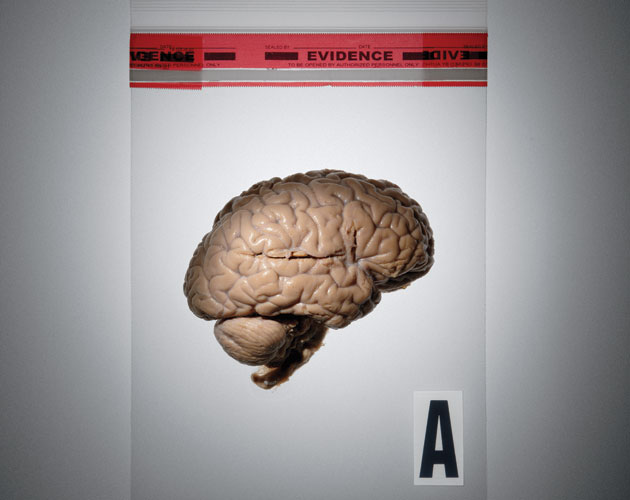

There’s an old criticism of neurology that some doctors incorrectly still believe applies today: that all that is done is “diagnose and adios!” Lang maintains, “This is clearly not the case, particularly in the field of Parkinson’s disease, where many effective treatments are now available.” Recently, enhanced versions of levodopa restore depleted dopamine, a brain chemical critical for motor control, and can significantly help people with Parkinson’s to overcome problems with tremors and balance difficulties. It’s important to remember that all these symptoms are caused by the loss of neurons in the substantia nigra, a small, peanut-sized region in the centre of the brain that modulates conscious movements.

At the fore of the Krembil Neuroscience Centre’s research realm, Lang is currently working on a large number of important studies trying to address the critical question of what causes Parkinson’s disease, how we can diagnose it more accurately, especially at the earliest stages, and what can we do to stop its inexorable progression. “These studies involve collaborators who are doing research techniques including molecular biology, neurophysiology, family and population studies, brain imaging, drug development and others,” he explains. “I think we also have to emphasize the role of serendipity – we can’t close doors.”

UPDRS RATINGS

Hays could hear the quiet shuffle of interns’ shoes as they filed into the small examination room where she sat with eyes closed in front of Lang. When she opened her eyes, his right hand extended toward her. “Okay,” he said, “now touch the tip of my finger.” She did, then he asked her to tap her fingers together. Ten seconds later, she tapped each foot as hard as she could against the flecked, rubber-tiled floor – and so the test went.

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) – one of the most universal measures of examinations – consists of four parts. The first two are based on data provided by the patient regarding performance at home in a variety of daily activities (showering, dressing, walking, eating). The other two involve an examination conducted by the neurologist to determine if the patient is experiencing stiffness in the neck or the limbs, slowing of movement of hands or feet, a tremor when arms are extended or at rest, the ability to get up out of a chair effortlessly and, lastly, if the gait is normal.

Hays had risen to the challenge of these examinations, trying her best to score well (which is low) on them. She was using a sort of reverse psychology on herself: if she succeeded, the doctors would give her a better diagnosis, and the whole thing would become a self-fulfilling prophesy. Funny thing was though, it worked. She scored 16 on the first visit and even lower – 11 – on the second visit six months later. When the doctors stepped out of the room, she would look at her results on the computer screen, memorizing her scores.

SMART MOVES

“With aging, heading off the progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s starts with lifestyle,” says Lang. “Regular rest periods and avoiding stress are key.” He strongly believes that patients who maintain healthy lifestyles can prevent complications presented by common diseases such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes.

Another important factor is the recognition of the role of exercise. “Staying active has a variety of ways of impacting health and brain function,” explains Lang. “In its most simplistic form, exercise simply improves our health, improves our mobility, improves our co-ordination, improves our general sense of well-being.”

Exercise not only helps with balance and co-ordination, but many neuroscientists like Lang theorize that exercise may have an influence on brain function itself. The growth-promoting effects on neurons hold the tantalizing possibility of brain tissue regeneration. “You will just function better if you are fit,” he sums up, adding, “This is an important component of a treatment plan that includes judicious and knowledgeable use of the many medications that we have at our disposal for the varied symptoms of the disease. Despite these options, we sorely need important breakthroughs, but we are very optimistic that these are on the horizon.”

Today, Hays feels like she’s back on track. “My fears have evaporated,” she smiles and continues, “The truth is I feel that I’ve become more focused.” Indeed. Hays is now thinking of adding piloxing, an invigorating mix of Pilates and boxing, to her ever-growing list of interests, which includes cycling, yoga and Spanish lessons. “Many people with Parkinson’s don’t know that they can improve their lifestyles considerably by keeping active,” she maintains. “Support plays an important role as well.” And with Dr. Lang’s encouragement, Hays plans to show others like her that there is hope in the journey to wellness.

(Zoomer magazine, May 2013)

The distinguished career and accomplishments of Dr. Anthony Lang will be celebrated at A Tribute to Tony on Wednesday, May 14, 2014 at The Carlu in Toronto at 6:00pm. Proceeds from this fundraising event will support a collaboration between The Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Edmond J. Safra Program in Parkinson’s Disease at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre, UHN. This collaborative research project will better the understanding of the effect of levodopa, the most common drug for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

To purchase tickets or donate, please contact:

Kirsten Liddell

Event Coordinator

Toronto General & Western Hospital Foundation

[email protected]

416-340-4800 ext. 6323