Caregiving requires long hours of hard work for no pay. CARP says urgent action is needed to help those who serve.

Canadians who provide care for loved ones at home have long been the overlooked — and overworked — minions in our health-care system.

Stricken by chronic diseases, ambulatory issues or cognitive impairment (often all three), patients must be taken to doctors’ appointments, fed, bathed, dressed and generally monitored on a 24-7 basis.

The involuntarily enlisted army of eight million Canadian informal caregivers (a million over the age of 65) performing this role must pick up the slack for an overwhelmed and underfunded home care system.

Their economic contributions are palpable — unpaid caregivers provide the equivalent of 1.2 million full-time jobs. If these services were performed by minimum-wage workers, it’s estimated the yearly bill would come to an astounding $25 billion.

While caring can be a labour of love, it’s still a job — and a time-consuming one at that. Caregivers must fit the many demands of their patient into busy schedules, while still looking after their own households, holding down jobs or even wrangling some downtime to relax and recharge the batteries.

When the patient has dementia, however, the task becomes even more onerous. Providing emotional support and care for a mother or father whose faculties have begun to slip away is physically, emotionally and financially draining.

“Besides the significant mental and emotional toll of caring for a loved one with dementia, it can hit us in the pocketbook,” says Wanda Morris, CARP’s vice-president of advocacy. “Caregivers often struggle with reduced – or no – earnings while incurring expenses ranging from medical supplies to nursing home fees. Cutting back on paid employment to provide care may also mean slower career and salary progression and reduced pensions or retirement savings.”

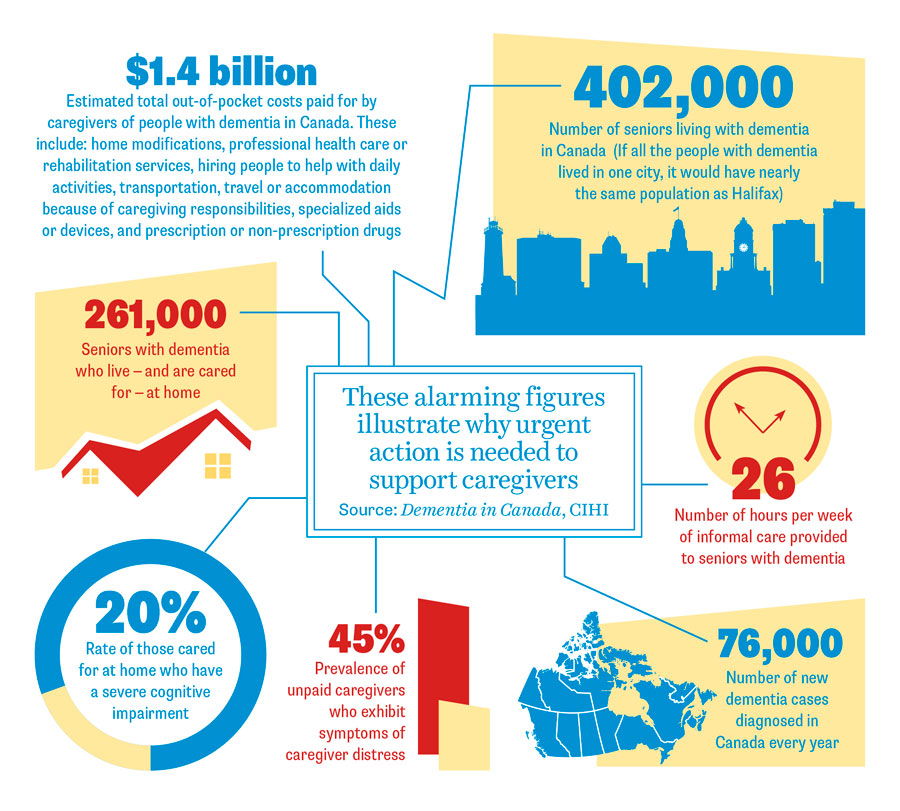

The Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) recently released Dementia in Canada, a digital report outlining the impact of dementia on seniors, caregivers and the health-care system. The numbers are shocking, especially the excessive burden placed on family caregivers.

“The CIHI report should serve as a wake-up call to governments on the importance of implementing a National Dementia Strategy,” says Morris. “The numbers are alarming. CARP is calling for a co-ordinated effort that helps both formal and informal caregivers and ensures Canadians with dementia will get the best possible care.”

CARP Recommendations

In its 2017 Caring for Caregivers campaign, CARP called for specific measures to help millions of caregivers on the verge of burnout. These included:

Provincial governments must clearly establish the right for flexible working arrangements for caregivers. The provinces must also align their employment standards with federal insurance benefits to provide a minimum of 27 weeks unpaid, job-protected caregiving leave.

Federal and provincial governments must improve financial supports by:

- Changing the existing non-refundable caregiver tax credit programs to refundable tax credits delivered as cash payments

- Implementing a benefit program where eligible caregivers are provided with a suitable monthly payment

- Federal and provincial governments must increase funding for continuing care services to facilitate aging in place, such as home care, home support and adult day services

- Provincial governments must ensure that caregivers have access to education and training programs, mental health supports and caregiver support groups.

- Visit: www.carp.ca/campaign/support-for-caregivers/