Have You Had Your Blood Tested for Iron? A Common Disorder Raises Risk for Disease

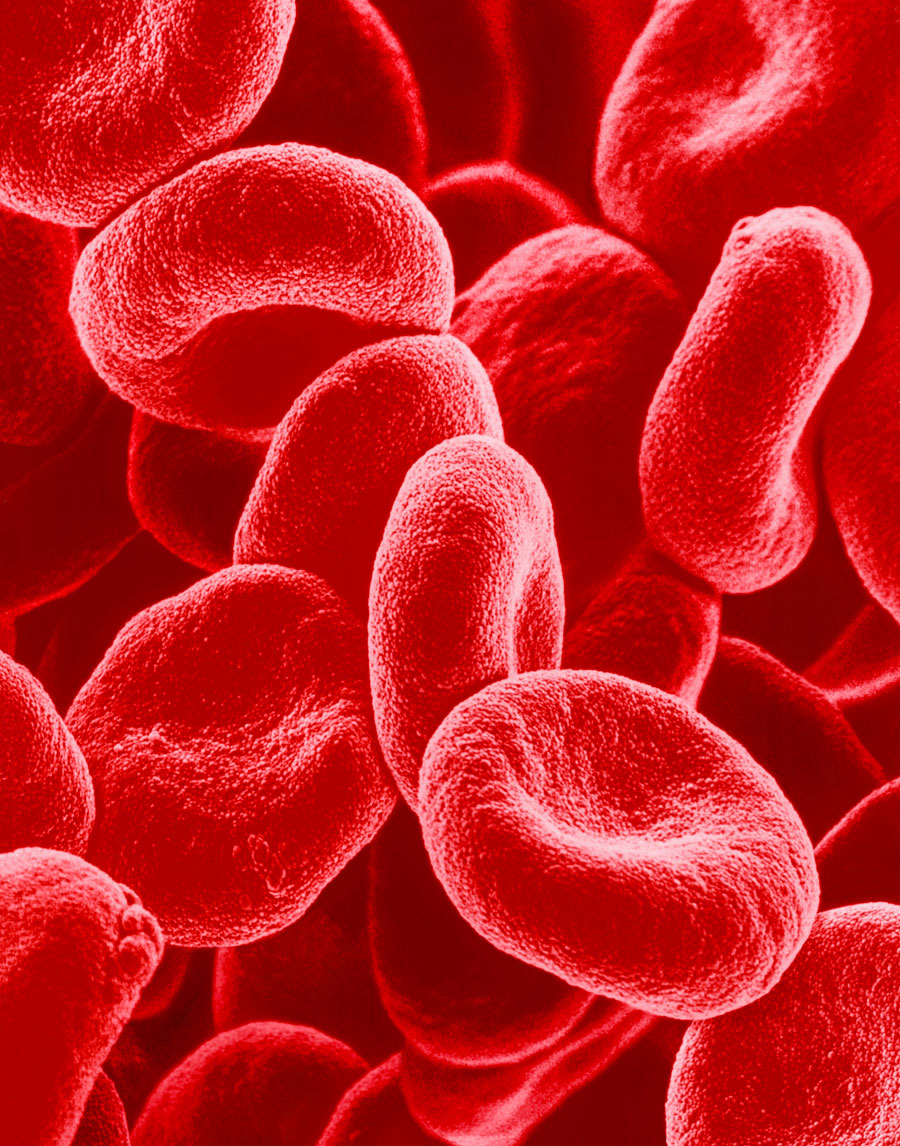

Photo: SUSUMU NISHINAGA/Getty Images

As if we need something new to worry about during this bleak mid-January, research published this week in the British Medical Journal provides evidence that the most common genetic disorder affecting Canadians does much more damage to many more people than was previously thought.

About one in 300 Canadians, mostly those of Northern European descent, are estimated to have two copies of the faulty gene that can cause hemochromatosis — a build-up of iron in the body, putting them at risk for the disease.

Hemochromatosis is linked to adult onset diabetes, osteoarthritis, sleep disorders, damage to organs such as the liver and heart, and other ailments.

“The liver and heart are particularly vulnerable, but the pancreas, endocrine glands, testes and ovaries, joints and skin can also be affected,” according to the Canadian Hemochromatosis Society (toomuchiron.ca).

Even more worrying, the damage it does to the body increases with age.

“Excess iron accumulation in people with hemochromatosis is chronic and ongoing,” states the CH Society. “It takes time for iron overload to reach a level that will cause organ damage and failure. Men typically develop the disease between 40 and 60 years of age, and women after menopause. Diet, vitamin pills with iron, and alcohol consumption all can have an effect.”

In fact, the symptoms of hemochromatosis are often mistaken for normal signs of aging, such as joint pain and extreme tiredness, reports the British Medical Journal.

Iron overload is most common in people from Northern Europe.

Previous studies suggested that very few people with the faulty HFE C282Y gene would develop hemochromatosis.

But researchers at the University of Exeter compared levels of illness and death among people aged 40 to 70 years with and without the gene mutations.

Hemochromatosis was diagnosed in 21.7 per cent of men and 9.8 per cent of women with the HFEC282Y mutations by the end of the seven year study — substantially higher than previous estimates.

What’s more, when their sample had an average age of 63, one in five more men and one in 10 more women with HFE C282Y mutations had developed liver disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, compared with people with no HFE C282Y mutations.

More disease developed at older ages, and there was also an increase in mortality in the mutations group overall, including 14 deaths from liver cancer.

But here’s the good news:

Hemochromatosis can be easily treated by the removal of blood (like a blood donation, only more frequent) at regular intervals until iron levels return to normal, advises the Canadian Hemochromatosis Society.

Unfortunately, because the prevalence and damaging effect of the disorder has not been fully recognized, older Canadians are rarely tested for iron levels.

And yet, says the CH Society, “A simple blood test can detect iron overload, but it is NOT part of the standard blood test ordered in conjunction with an annual check-up. Your doctor must specifically request an iron series profile on the lab requisition form. This is NOT the same as hemoglobin. If iron levels are elevated, DNA or genetic testing for the most common type of hemochromatosis is available and may be used to confirm a diagnosis.”

In other words, if you’re experiencing joint pain, tiredness, or high glucose levels, especially if you’re of Northern European descent, ask your doctor about ordering a blood test with an iron series profile.

“Up until recently, medical professionals were taught this was an extremely rare disorder, so your doctor may not be aware of it,” suggests the CH Society.

The new study published in the British Medical Journal this week will likely make a difference in recognizing the impact of this easily diagnosed and treatable disorder.

A self-assessment tool and more information are available at the Canadian Hemochroatosis Society website toomuchiron.ca.