#CleanEating: How the Food Revolution Has Changed Our Lives

Photo: Martin Barraud/Getty Images

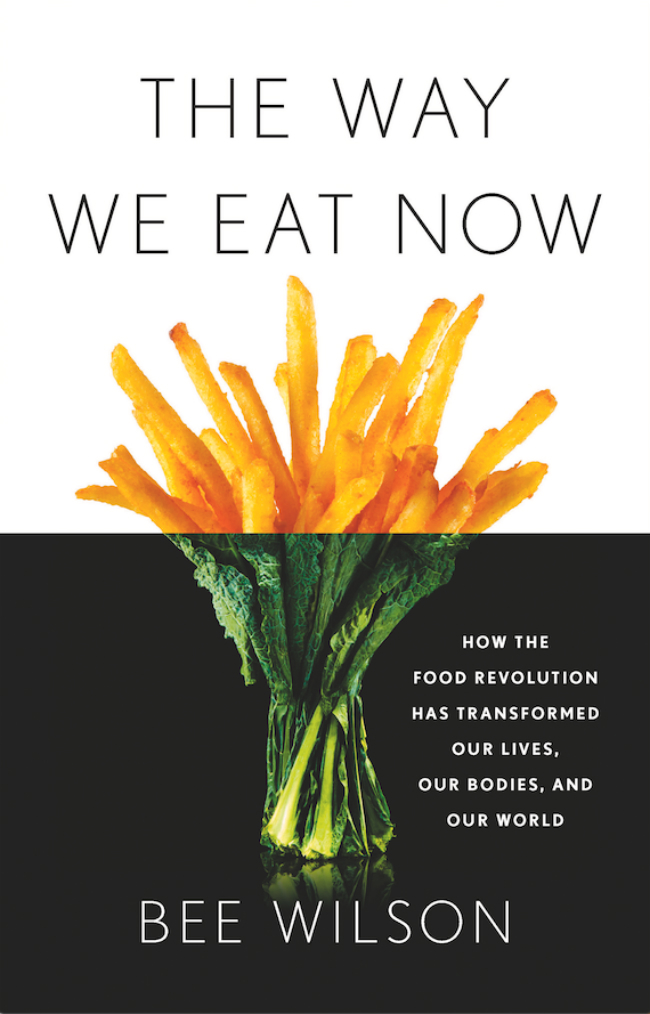

In her new book The Way We Eat Now, author Bee Wilson investigates how the food revolution has transformed our lives, bodies and our world.

At first, clean eating sounded modest and even homespun: rather than counting calories, you would eat as many nutritious home-cooked substances as possible. This was about taking all the toxic crayons out of the box and leaving only the good ones. But it quickly became clear that in many cases, clean eating was more than a diet; it was a belief system that propagated the idea that the way most people eat is not simply fattening but impure.

Seemingly out of nowhere, a whole universe of coconut oil, dubious promises, and spiralized zucchini has emerged. “I long for the days when clean eating meant not getting too much down your front,” the novelist Susie Boyt joked in 2017.

The rise of eating for wellness is a sign that millions of eaters have become so unmoored that we will put our faith in any master who promises us that we, too, can become pure and good and glowing with health, if only we can remove enough foods from our diets.

It is very hard to pinpoint the exact moment when clean eating started because it is not so much a single diet as a portmanteau term that borrowed ideas from numerous pre-existing diets: a bit of Paleo here, some Atkins there, with a few remnants of 1960s macrobiotics thrown in for good measure.

Sometime in the early 2000s, two distinct but interrelated versions of clean eating became popular in the United States – one based on the creed of real food and the other on the idea of detox. Once the concept of cleanliness had entered the realm of eating, it was only a matter of time before the basic idea spread contagiously across Instagram, where fans of #eatclean could share and parade their artfully photographed green juices in Mason jars and rainbow salad bowls.

The first and more moderate version of clean food originated in 2006 when Tosca Reno, a Canadian fitness model, published a book called The Eat-Clean Diet. In it, Reno described how she lost 75 pounds and transformed her health by avoiding all overrefined and processed foods, particularly white flour and sugar. A typical Reno “eat-clean” meal might be stir-fried chicken and vegetables over brown rice, or almond-date biscotti with a cup of tea. In many ways the Eat-Clean Diet was like a hundred other diet books that came before, advising plenty of vegetables and modestly portioned home cooked meals. The difference was that she did not call it a diet at all but a holistic way of living.

Meanwhile, a second version of clean eating was spearheaded by Alejandro Junger, a former cardiologist from Uruguay. Clean: The Revolutionary Program to Restore the Body’s Natural Ability to Heal Itself was published in 2009 after Junger’s “clean” detox system had been praised by actress Gwyneth Paltrow on her Goop website. Junger’s clean system was far stricter than Reno’s, requiring, for a few weeks, a radical elimination diet based on liquid meals and a total exclusion of caffeine, alcohol, dairy and eggs, sugar, all vegetables in the nightshade family (tomatoes, eggplants, and so on), red meat (which according to Junger creates an acidic “inner environment”) and other foods. After the detox period, Junger advised very cautiously reintroducing “toxic triggers” such as wheat (“a classic trigger of allergic responses”) and dairy (“an acid-forming food”).

To read Junger’s Clean is to feel that everything edible in our world is potentially toxic. “Who is the candidate for using this program?” Junger asks. “Everyone who lives a modern life, eats a modern diet and inhabits the modern world.”

We are living in an environment where ordinary food – which should be reliable and sustaining – has come to feel noxious in ways that we can’t fully identify. In prosperous countries, large numbers of people, whether they want to lose weight or not, have become understandably scared of the modern food supply and what it is doing to our bodies. When normal diets start to sicken people, it is unsurprising that many of us should seek other ways of eating to keep ourselves safe from harm.

Our collective anxiety around diet has been exacerbated by a general impression that mainstream scientific advice on diet – inflated by newspaper headlines – cannot be trusted. First these so-called experts tell us to avoid fat, then sugar, and all the while people get less and less healthy. What will these experts say next, and why should we believe them?

Into this atmosphere of anxiety and confusion stepped a series of wellness gurus offering messages of wonderful simplicity and reassurance: eat this way and I will make you fresh and healthy again. These gurus were able to find receptive readers and followers in part because of the failures of conventional medicine to address the question of food. Over the past 50 years, mainstream health care in the West has been inexplicably blind to the role that diet plays in preventing and alleviating ill health.

When it started, #eatclean spoke to growing numbers of people who felt that their existing way of eating was causing them niggles, from weight gain to headaches to stress, and that conventional medicine was unable to help. In the absence of nutrition guidance from doctors, it was a natural step for individuals to start experimenting with cutting out this or that food, from dairy to gluten. The gurus of wellness urged us on in such restrictions. Amelia Freer, in her 2015 book Eat. Nourish. Glow, admits that “we can’t prove that dairy is the cause” of ailments ranging from irritable bowel syndrome to joint pain but concludes that it’s “surely worth” cutting out dairy anyway, just to be safe.

In another context, Freer writes, “I’m told it takes 17 years for scientific knowledge to filter down” to become general knowledge, while advising that we should all avoid gluten in the meantime as a blanket precaution.

On the basis of such pseudo-science, millions of us have started to look with terror on a range of basic and nourishing foods, including pasta and noodles, which are sometimes referred to in the clean eating movement as “beige carbs.” Like fat in the 1980s, gluten has come to be viewed by some as a pollutant, something that could contaminate a whole plate of food with a single speck. Only around one per cent of the population actually suffers from celiac disease, an autoimmune disease in which the gut lining is damaged by gluten, the protein found in wheat, rye and barley. A further small segment of the population may be suffering from a much milder – and still controversial – condition known as nonceliac gluten sensitivity, whose symptoms include brain fog, stomach pain and bloating.

But these two conditions together cannot begin to explain why one hundred million Americans, or a third of the population, say (according to industry data) that they are now actively avoiding gluten. I have celiac friends who claim that #eatclean has made it far easier for them to buy ingredients that they once had to go to specialist health-food stores to find. But it is sad that so many other people should have forced themselves to abandon once-beloved foods and buy expensive gluten-free replacements for no good reason, in the name of wellness.

For as long as people have eaten food, there have been diets and quack cures, but previously, these existed, like conspiracy theories, on the fringes of a food culture. The clean eating of recent years is different because it has established itself as a challenge to mainstream ways of eating, and its wild popularity over the past few years has enabled it to move far beyond the fringes. Powered by social media, it has been more absolutist in its claims and more popular in its reach than any previous school of nutrition advice, outside the systems of dietary taboos created by religions.