Cancer From Textured Breast Implants Almost Cost Terri McGregor and Other Canadian Women Their Lives

When Terri McGregor got her breast implants in 2009, she was told the greatest risk was from the anaesthetic. Six years later, she underwent explant surgery, chemotherapy, a stem-cell transplant and radiation to treat breast-implant associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Photo: Courtesy of Terri McGregor

Terri McGregor was a hair girl. Blessed (cursed!) with a head of thick curls, she remembers her teen years back in the ’70s as a time when her only concern about her looks was centred around preventing frizz. Even gender was irrelevant. As the only daughter in a family that owned a paving company near North Bay, Ont., she was expected to work as hard as her two brothers, just as her mother worked as hard as her father.

“I didn’t grow up in a space where how you looked had any relevance in life,” says McGregor.

As far as body image went, McGregor considered herself normal, her B-cups well suited to her five-foot-three-inch frame. In fact, the only time she remembers breasts being an issue was one day when, shortly before graduating from high school, her mother was urging her to get a new bra for extra support, and lifted her own shirt to show Terri what can happen after pregnancies.

“I remember being shocked and thinking, oh my god, they’re like socks with tennis balls!”

Two children and two-and-a-half decades later, hoping to restore her own battle-worn breasts, McGregor paid $8,500 to get breast implants in 2009 — a decision that would almost cost the then 44-year-old her life.

Breast implants join drugs and devices under fire

Manufacturers of drugs and medical devices are under increasing scrutiny for failing to accurately represent the risks associated with their products to doctors and patients.

In Canada and the United States, drug maker Sanofi recently recalled Zantac, its over-the-counter heartburn remedy, amid concerns that an active ingredient found in another 11 voluntarily recalled products may contain a probable carcinogen. Purdue Pharma, the makers of Oxycontin, filed for bankruptcy shortly after reaching a tentative mega-billion-dollar, opioid-related settlement in the U.S. Now the B.C. government , recently joined by Alberta, has a similar class-action suit against Purdue and other drug companies to try to recover health care costs of treating opioid addictions and overdoses.

Even Johnson & Johnson, associated with innocuous products like baby wipes and Band-Aids, is embroiled in litigation. The health-care giant, one of several companies being sued over their role in fueling the opioid epidemic, is facing or has recently settled lawsuits concerning baby powder, transvaginal pelvic mesh implants, an anti-psychotic drug and a blood thinner.

Amid this maelstrom of bad news for “big pharma,” once again, breast implants are back in the headlines; once again, they’re making women sick. And once again, while regulatory health bodies scramble, manufacturers quake, and lawyers prepare for combat, women around the world are reeling with feelings of fear, outrage, bewilderment and betrayal. How could this happen again?

Back in 1992, Canada and the U.S. imposed a moratorium on silicone-gel implants largely over reports of high rupture rates and links to autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. (Saline-filled implants were not affected by the ban.) It was lifted 14 years later, in 2006, after Health Canada said it reviewed more than 65,000 pages of documents and could find no proof the implants caused illness like auto-immune diseases.

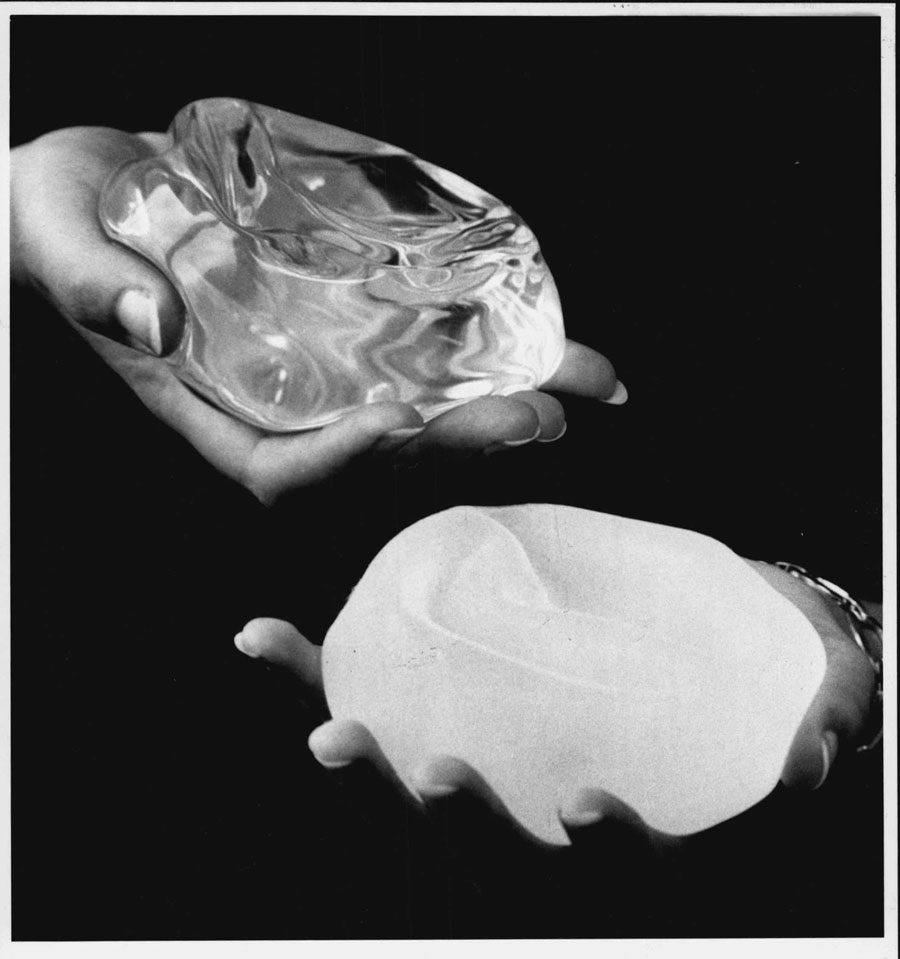

This time around, the gel filling is not under suspicion, but rather a certain type of shell. Textured implants, which have a sandpaper-like surface meant to help hold them in place, are associated with a higher risk of breast-implant associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), a serious, non-Hodgkin lymphoma that affects the immune system, not breast tissue.

In May, following the lead of France and other nations, and after its own extensive safety review, Health Canada banned Allergan Biocell breast implants, the only macro-textured implants available in Canada. An agency statement said the risk of BIA-ALCL, estimated at one in 3,565, outweighed its benefits. There are 26 confirmed cases in Canada with no deaths so far. Smooth-shelled implants, filled with silicone or saline are still available and there are no confirmed reports implicating these products in BIA-ALCL cases.

In July, under pressure from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Allergan announced a global recall of its Biocell textured implants and tissue expanders. To date, the FDA reports 573 confirmed cases of BIA-ALCL globally and 33 deaths.

The numbers could climb in part because the lymphoma grows slowly (usually in the scar tissue surrounding the implant) and often takes several years to present. The median amount of time from implant to diagnosis is nine years; the median age at diagnosis is 53.

McGregor was 50 when she was diagnosed with BIA-ALCL. Her decision to get textured, silicone-gel filled implants came three years after the 14-year moratorium on silicone implants was lifted.

“As a consumer, I thought if they were back on the market – well, I made a huge assumptive mistake that they were safe. The new marketing was just the beginning of the misinformation.”

It’s not like McGregor didn’t do her homework. In fact, she remembers the plastic surgeon saying that she was a textbook case of the post-baby market of mature women who had done their research.

“It made me feel safe,” she says.

McGregor was told there was a risk of rupture, which was minimal, but the greatest risk was the anaesthetic, which is true of most surgeries. And so she went ahead with the procedure.

In 2015, during a routine mammogram, the technician had difficulty moving her left breast. This first sign of trouble led to multiple tests and doctor visits, where ruptured implants were detected. During surgery to remove and replace them, doctors saw tumours on scar tissue around an implant, which prompted more tests. She was diagnosed with stage 4 breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) .

McGregor’s treatment included several rounds of chemotherapy, a stem-cell transplant and radiation. Emotionally, she was left with a crippling sense of guilt and shame that she had, in fact, given herself cancer.

“I felt shame not over what I’d done, but the shame of watching my family suffer, my mom, my sons, my husband … the pain and suffering they had to go through. But I went from ‘I gave myself cancer’ to ‘I have a man-made cancer that could have been avoided if I’d known that it was a risk.’”

Cancer Out, Cancer In

Silicone breast implants were developed by two plastic surgeons in Texas in the early 60s; the first breast implant procedure was performed in 1962. Today, breast implants are used in cosmetic surgery to alter the appearance of the breast; reconstruction surgery to rebuild the breast after a mastectomy; and “top” surgery for transgender women. Cases of BIA-ALCL have been diagnosed in all.

Daiva Hoover, 65, of Toronto, is a breast cancer survivor who has been through the unfathomable ordeal of opting for reconstruction surgery only to find out the implants have given her cancer.

After her breast cancer diagnosis in 2002, Hoover had her left breast and ovaries removed. She remembers a family vacation to the Caribbean shortly after where, on a nude beach, she roamed around one-breasted, lollygagging in the luxury of knowing no one cared. But once she was back home, things were different and she became a master at fashioning scarves to mask her asymmetrical shape. A few years later, after a test for the genetic mutation called BRAC1 predicted an 85 per cent chance of getting cancer in the right breast, she elected to have it removed. It was then that she started to consider reconstruction surgery.

Because Hoover’s body didn’t have enough fat to opt for the graft method that uses fat from other parts of the body, implants were her only option. The selection of shapes and sizes surprised her.

“I didn’t want bulbous, I didn’t want augmentation, I just wanted to be neutral, the way I was, and this particular one was like a nice teardrop, just like a nice normal breast, and I went, ‘yeah, that looks good!’”

She was pleased with the results and anxious to get on with her life, so she didn’t even bother to go back to get nipples. “I somehow just forgot about it. I didn’t care, my clothes fit, everything was fine.”

And then, in the spring of 2013, it wasn’t.

Suddenly, Hoover’s left breast swelled up and after making the rounds to different doctors (she was prescribed antibiotics several times) she was finally diagnosed with BIA-ALCL.

“I was devastated. How else would you feel? Knowing you’d beaten the cancer, you’d had everything taken out of your body and then they go, surprise, you have lymphoma.”

Explant surgery left her completely concave. Because textured implants have a higher surface area, which could be a factor contributing to the risk of BIA-ALCL, they can be, as was in Hoover’s case, difficult to remove. Her surgeon explained that she had to scrape and dig the implants out. Chemotherapy treatments landed Hoover back at Toronto’s Princess Margaret Hospital — “my old alma matter,” she says.

“I am angry that we weren’t issued a warning to say hey, we found this, but this is your choice. I wonder how long they knew.”

Who knew what and when?

According to the National Center for Health Research, a U.S. not-for-profit, the FDA first reported a possible association between breast implants and the development of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) back in 2011. In 2014, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network released a worldwide oncology standard for surgeons and oncologists to test for and diagnose breast implant associated ALCL. In 2016, the World Health Organization recognized the illness and designated BIA-ALCL as a T-cell lymphoma. It wasn’t until 2017, however, that the FDA updated its website to make it official – breast implants could cause this form of cancer.

Legally, the who-knew-what-when question is huge.

“The lawsuits we have brought against Allergan on behalf of women with BIA-ALCL are based on a manufacturer’s duty to warn consumers of any dangers it knows or ought to know are inherent in the use of its product,” says Tanya Pagliaroli of TAP Law in Toronto, who is representing some of the women in this story. “This is a continuing duty that would apply not only at the time these women received their implants, but continues and extends to any dangers the manufacturer discovers subsequently.”

The rationale for the law, she says, is to correct the imbalance of information between consumers and manufacturers. If the women were not properly warned of the risk of lymphoma, their right to make an informed decision was infringed. Their choice, then, was not an informed one.

Much is at stake.

The 90s were marked with lawsuits adding up to billions that drove some manufacturers from the breast implant business altogether, and manufacturing giant Dow Corning into bankruptcy. Today, breast augmentation is big business. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons 2018 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report, it reigns as the top cosmetic surgical procedure, part of $16.5 billion spent on cosmetic procedures in the U.S. last year.

Here in Canada, similar numbers are not available. Nor are statistics regarding how many breast augmentations are performed each year. The Canadian Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery says health care is a provincial domain and, although a federal breast implant registry is in the works, currently there is no way to determine the total number of breast implant procedures performed in private practices. However, statistics from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) show 5,214 breast implant procedures were performed in 2017-2018 in hospitals across Canada (excluding Quebec), 2,883 of them for cosmetic purposes.

Monitoring in the meantime

For those without symptoms of BIA-ALCL, Health Canada does not recommend the removal of Biocell or other types of implants. The agency, along with other international regulatory bodies including the FDA, advises people to monitor their breasts for changes and consult a health care professional if they experience any symptoms like: sudden swelling or enlargement of the breast; a lump or mass; skin changes and capsular contracture, a complication that occurs when scar tissue forms around the implant and causes the breast to become hard or appear misshapen.

Not surprisingly, Health Canada’s advice has left some asymptomatic women feeling anxious. When Sarah Lovely, 52, of North Vancouver, B.C., visited her doctor in June, she was there to ask about the implications of breast implant removal not because of the cancer link – she hadn’t even heard the news – but because she’d had her implants for 17 years (she paid $9,000 for the procedure at the time) and was considering going implant-free.

“I wasn’t the same person that I was when I got them,” she said. “And, they were in need of replacement.”

During the process of explaining her dilemma, the doctor interrupted and told her about the ban. She couldn’t believe it when he proposed that they could leave the implants in and monitor the situation.

“How about you take them out, stick them in a jar, and you watch them all you want and keep me posted?” she said. Shortly after her appointment, she paid approximately $4,000 to have the implants removed and another $5,000 for a breast lift.

Of course, many women don’t have much choice but to follow Health Canada’s advice. Explant surgery can cost several thousands of dollars and, in the absence of a specific medical diagnosis, is not covered by insurance. There is some concern that surgery may do more harm than good, and whether removing textured implants reduces cancer risk is unproven.

At the time of this writing, Lovely reports that tests for lymphoma came back negative; Hoover has undergone successful reconstruction surgery this time using her own body fat; and McGregor is recognizing the three-year anniversary of her last cancer treatment. Happily, her thick curly hair came back after the chemo treatments, but she is far too busy with advocacy work to fret about frizz.

Instead, the co-founder of the patient advocacy website biaalcl.com recently attended the ASPS conference in San Diego where for the first time, patient advocates were included in panel discussions and meetings with plastic surgeons and manufacturers, and she just returned from the first World Consensus Conference BIA-ALCL in Rome. She wants to end “the misleading and dangerous narrative that the lymphoma is exceedingly rare, easily diagnosed at early stages, and easily curable.” She says this level of denial and dismissiveness is unacceptable and ignores the complexity and seriousness of the cancer.

McGregor is part of a surge of advocacy groups across the country that are fighting for better research, more accountability, and absolute transparency — anything and everything to make sure this never happens again.

RELATED:

Health Canada Splits With FDA, Banning Biocell Breast Implants Linked to Cancer

Textured Breast Implants Linked to Cancer Recalled Worldwide Two Months After Canadian Ban