No Place to Grow Old: How Long-Term Care Ignored the Lessons From the First Wave of COVID-19

A resident of the Lynn Valley Care Centre seniors facility in North Vancouver, which recorded Canada’s first death from the virus on March 8, 2020. From deficiencies in infection control to understaffing, many of the problems that were present in long-term care during the first wave of the pandemic have gone unaddressed. Photo: The Canadian Press/Darryl Dyck

Today, is World Elder Abuse Awareness Day — a United Nations initiative that aims to “share information and promote resources and services that can help increase seniors’ safety and well-being” as well as “to mobilize community action and engage people in discussions on how to promote dignity and respect of older adults.” Part of that includes spotlighting the plight of residents of long-term care homes.

Investigative journalist Alex Roslin won the 2020 Dave Greber Freelance Writers Award for his feature story “Canada’s Hidden Shame: How COVID-19 Exposed Years of Systemic Neglect in Long-Term Care,” from Zoomer’s July/August 2020 issue.

So today, we look at Roslin’s follow-up story from Zoomer’s April/May 2021 issue, in which he revisits the tragedy of thousands of avoidable pandemic deaths in Canadian long-term care homes and examines how “the problems behind the seniors homes horror show are in many cases unaddressed more than a year since the pandemic started last March.”

No one can say we didn’t see it coming. The second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was widely prognosticated long before it hit. And it didn’t take a rocket scientist to surmise that seniors residences would, again, be ground zero of the pandemic in Canada, much as they were last spring when eight in 10 Canadians who died of COVID-19 lived in long-term care and retirement homes. It was one of the most disastrous records in a world replete with disaster.

Yet, prepare we did not. At least not very well. From infection control to understaffing, despite some amelioration, the problems behind the seniors homes horror show are in many cases unaddressed more than a year since the pandemic started last March.

After a lull in cases last summer, COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths shot up across Canada in the fall, soaring back toward the highs seen last spring. In some provinces the second wave was worse than the first. In Alberta, lax health rules contributed to a devastating COVID-19 resurgence, with the hospitalization rate rising to 16.3 per one million people in late December, 10 times the peak of 1.6 last April, and an average daily death toll that reached 34 at the peak of the second wave in mid-January, up from two to four average daily deaths last spring.

Manitoba was hit even harder. It had a peak of 40 daily new cases in the first wave, but the second wave saw 300 to 500 infections on many days in November and December, before declining to 100 to 200 cases a day in January. By Oct. 1, only 20 Manitobans had died from the virus; as of Feb. 28, that number had skyrocketed to 895.

COVID-19 deaths started to decline nationwide in late January, but the number of new cases stopped falling in late February and had even bounced back up, possibly due to deadlier, more infectious variants like the one that killed more than half of the residents of a Barrie, Ont., nursing home in January and February. With a slow vaccine rollout and the spectre of a dreaded third wave driven by the new virus strains, it’s a race against time.

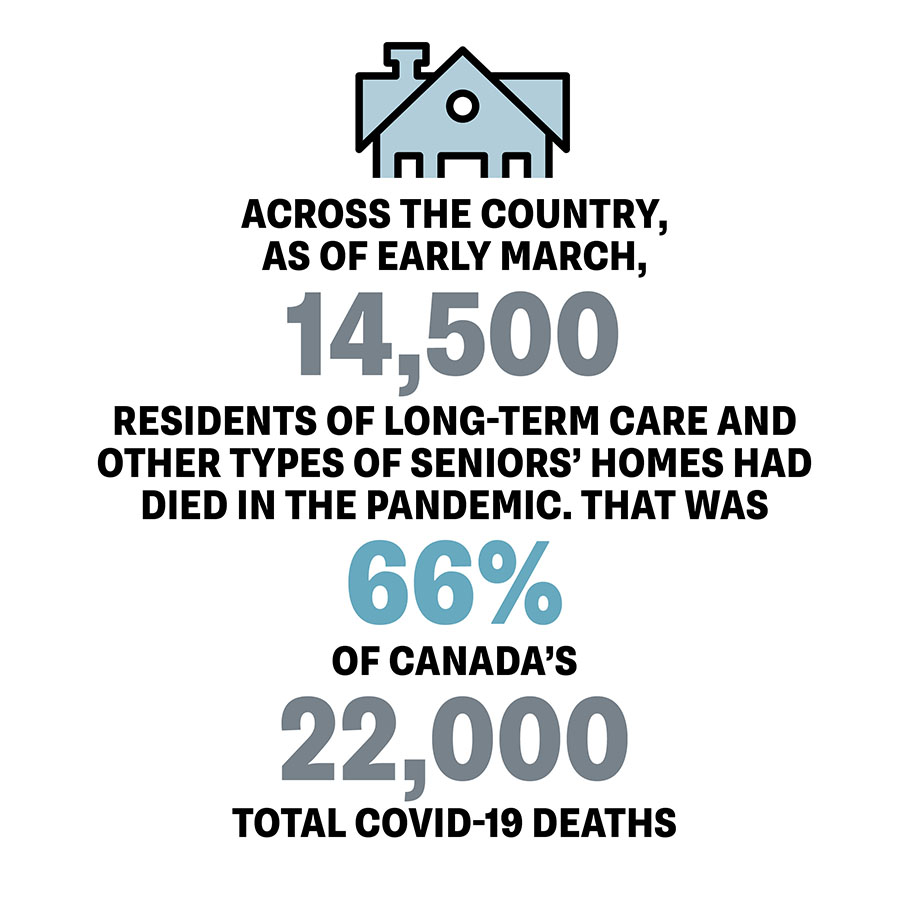

Across the country, as of early March, 14,500 residents of long-term care and other types of seniors homes had died in the pandemic. That was 66 per cent of Canada’s 22,000 total COVID-19 deaths, according to data from Ryerson University’s National Institute on Ageing (NIA), which tracks COVID-19’s impacts on seniors. It is lower than the 80 per cent recorded between March and early May during the first wave, but Canada’s rate is still far higher than the 41 per cent average found in 22 countries in a February study by the International Long-Term Care Policy Network. The U.S. rate was 39 per cent.

“We’re still one of the worst in the world,” said Dr. Samir Sinha, the NIA’s director of health policy research and one of Canada’s leading geriatricians. Sinha said many of the same problems are fuelling the devastation in the second wave as in the first. These include a patchwork of “highly variable” infection-control rules in every province and territory, chronic understaffing, and antiquated homes with “ward” rooms of up to four residents each where virus outbreaks are especially rampant. “Lo and behold, again some of the worst outbreaks are in these older homes. These are avoidable deaths.”

Bill VanGorder, chief policy officer at C.A.R.P., Canada’s largest advocacy group for older Canadians and a not-for-profit affiliate of ZoomerMedia, says little has been done to improve the conditions in long-term care. “We’re getting promises for future changes, but nothing much for the immediate term.”

On top of the problems Sinha listed, VanGorder said staff in the homes still lack access to adequate protective equipment, while Canadian provinces woefully underfund home-care services, forcing thousands of seniors into long-term care facilities where they’re more vulnerable to communicable diseases.

“Canada lags behind all other OECD [Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development] countries on home care,” VanGorder said. “We’ve got to change this warehousing of seniors in huge hospital-like facilities that are a remnant of the old poor houses. C.A.R.P. has been talking about all these problems for years, and now we’re paying the price for the fact that it was ignored.”

That message has been highlighted repeatedly during hearings that started in September before Ontario’s Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission, which has shed light on the bungled and slow-moving government response in a province where, as of March 8, 4,293 of 7,056 COVID-19 deaths were in seniors residences. The testimony has confirmed “there were many disconnects between what the science and evidence were showing needed to be done, the overall understanding of the issues at hand and the overall actions that were taken by the government,” Sinha said. “Our results speak for themselves.”

At the privately owned Sunnycrest Nursing Home in Whitby, Ont., all but one of 119 residents caught COVID-19 and 30 died in an outbreak that started in November and ended on Jan. 1. A provincial inspection found lax infection control, a lack of protective equipment and staffing below 50 per cent of normal levels, with the inspector reporting it caused “actual harm to residents.” Sunnycrest was ordered to remedy nine failings and a local hospital assumed its management for at least 90 days.

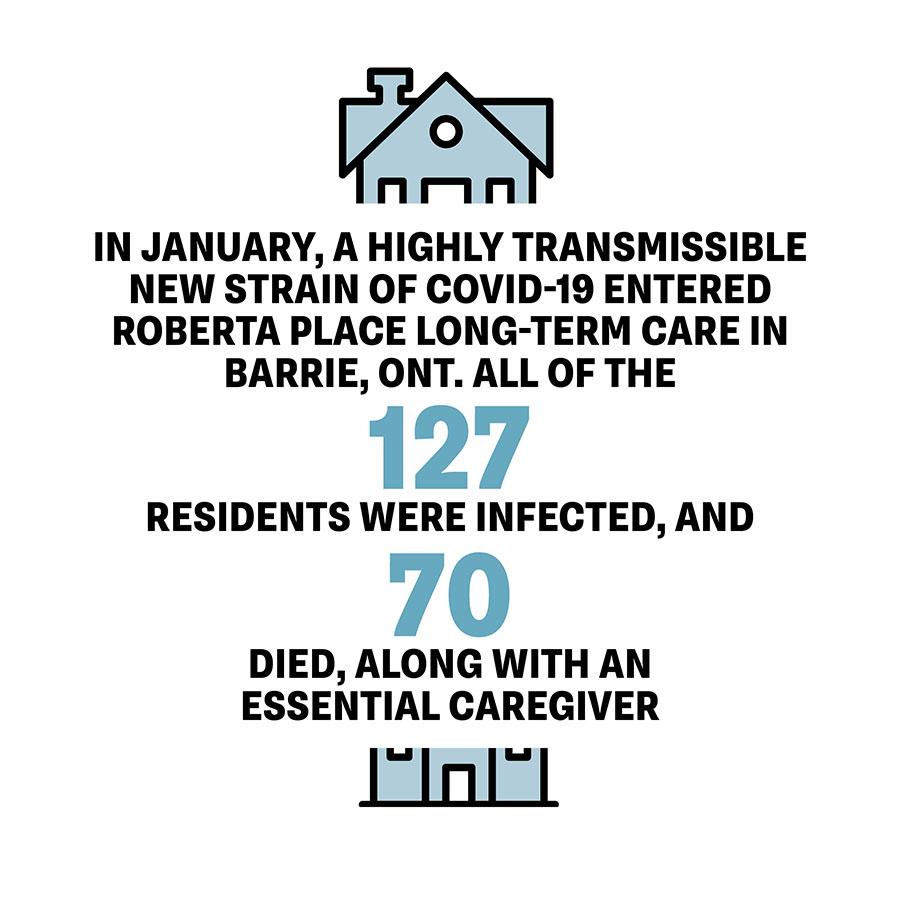

In January, a highly transmissible new strain of COVID-19 entered Roberta Place Long Term Care in Barrie, Ont. All of the 127 residents were infected, and 70 died, along with an essential caregiver. A provincial inspector who visited the privately owned home during the outbreak said the company had “failed to ensure that the home was a safe and secure environment for its residents,” noting that sick residents were sharing rooms with people who hadn’t tested positive. Earlier inspection reports during the pandemic found the home wasn’t complying with infection control rules.

In February, residents’ families filed a proposed $50-million class-action lawsuit against Roberta Place in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, claiming the home had been “reckless, irresponsible, and neglectful” and “failed to ensure adequate staffing levels.”

Understaffing remains a significant problem across Ontario, despite efforts to hire more workers after the first wave, said Dr. Bob Bell, a

former deputy health minister of Ontario and an orthopedic surgeon. “We have to put more money into the nursing and personal care envelope [of the provincial budget for care homes].” Hiring more staff was a key recommendation of a study Bell led, released in December, of COVID-19 lessons learned for Revera, one of Canada’s largest private long-term care home operators.

That study found another failing: many provinces still don’t require regular testing for seniors home staff. This is critical because symptoms take an average of five days and as many as 14 days to appear, during which time infected people can unknowingly transmit the virus. “Adequate surveillance testing is not there in Canada. I would say it should be done as often as every shift. I’m advocating to everyone: ‘Test, test, test,’” Bell said.

Testing is just one area where standards vary wildly among provinces and territories, and sometimes even between neighbouring communities. “Directives in one public health unit differ from those a kilometre away. We really need to have consistent standards across the province and nationally,” Bell said.

The failings prompted a withering rebuke in late January from more than 300 Ontario doctors and advocates who signed a letter blaming the province for allowing “a grave humanitarian crisis” to unfold. “The Ontario government has taken little immediate action in implementing … expert recommendations to improve staffing levels, increase training and improve infection control practices,” said the letter, organized by Doctors for Justice in LTC. “The government has allowed the situation in our LTC homes to become a preventable and recurring crisis during the 2nd wave.”

The province’s inaction also spurred C.A.R.P. to launch a campaign calling on Ontario Premier Doug Ford to fire his long-term care minister, Merrilee Fullerton. More than 7,200 people had signed the group’s online petition as of March 1.

The same issues are present from coast to coast in the second wave. In Winnipeg, almost 80 per cent of the Park Manor Care Home’s 82 residents were infected starting in early November, killing 13. Nearly 30 workers were also off sick, leaving the non-profit home so understaffed that CEO Abednigo Mandalupa had to come in on the weekend to do laundry. Mandalupa told CBC News the virus spread so widely because most residents live two or four to a room. What’s worse, staff didn’t get N-95 masks from the Winnipeg Health Authority until 20 days later because priority was given to more serious outbreaks, according to the CBC story.

The facility was one of 48 Winnipeg long-term care and other

seniors homes with outbreaks in early December. Opposition NDP Leader Wab Kinew slammed the Manitoba government for “the terrible toll that lack of preparation exacted on our seniors,” the Winnipeg Free Press reported. Sinha agreed that little was done in Manitoba to get ready for the second wave. “It’s been sad to see that we had a summer of opportunity to get the homes well prepared, but sadly a lot of provinces closed their eyes and hoped for the best.”

At the federal level, the Trudeau government has sidestepped calls for a public inquiry. Nearly a year after the health crisis started, Ottawa has yet to regularly publish detailed basic nationwide data on COVID-19 outbreaks and deaths in seniors homes.

A federal fiscal update in November pledged national standards to “address critical gaps in long-term care facilities, including raising the working conditions of lower-wage essential workers,” and $1 billion for long-term care, contingent on collaboration with provinces and territories.

But the initiative got a sceptical reception from provinces such as Ontario and Quebec that are wary of federal encroachment on their health turf. The Trudeau government has also stalled on responding to long-standing provincial demands, rejuvenated by COVID-19, for more federal transfer money for health care. Ottawa used to pay 50 per cent of costs, but now covers just $42 billion of the $188 billion total, or 22 per cent. The premiers want $28 billion in extra federal funds to bring Ottawa’s portion to 35 per cent of next year’s forecast total of $199 billion in health-care spending.

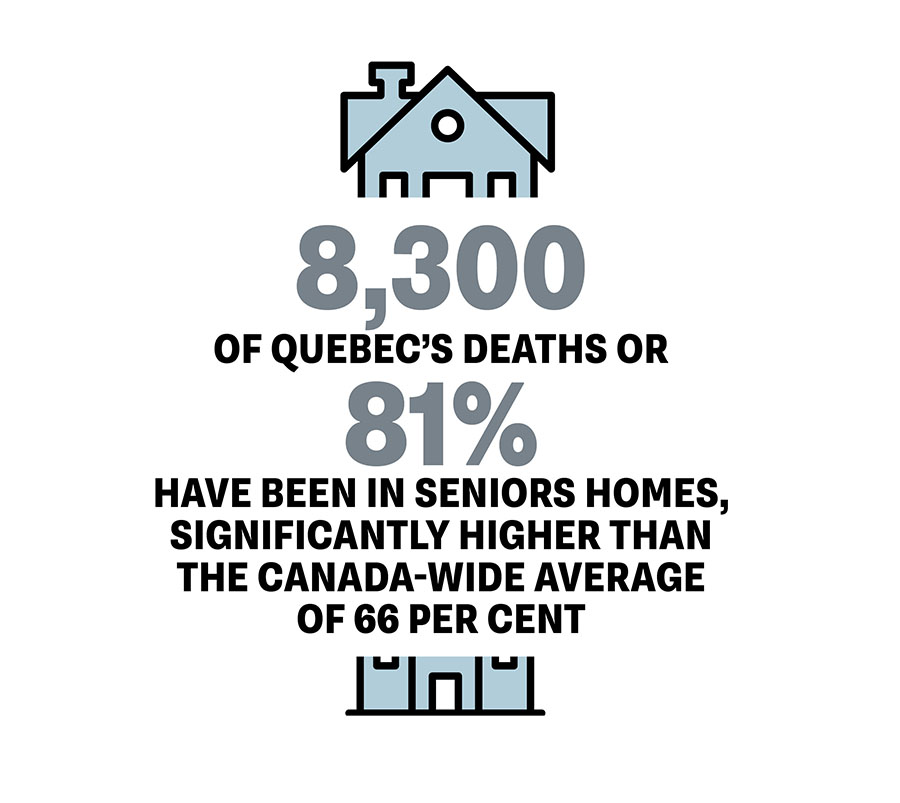

As in the first wave, the worst death toll is in Quebec, where there have been 10,300 COVID-19 fatalities, or nearly half of the 22,000 lives lost across Canada as of early March. Quebec public health institute data shows that more than 8,300 of Quebec’s deaths, or 81 per cent, have been in seniors homes, significantly higher than the Canada-wide average of 66 per cent.

“Clearly we still have problems,” said Dr. Quoc Dinh Nguyen, a geriatrician at the University of Montreal Hospital Centre who led a Quebec government panel that studied the lessons of the first wave of COVID-19. “It’s better than in the first wave, but we still lack personnel and testing.”

In some homes, he said as few as 30 per cent of staff follow voluntary provincial guidelines calling for regular COVID-19 tests every week, two weeks or month, depending on the region’s COVID-19 alert level. Pierre Lynch, president of AQDR, a 25,000-member seniors rights association in Quebec, estimates only about 70 per cent of all staff who work in seniors homes are getting tested regularly. “It’s important to test (all) the staff. They’re the ones going out of the building.”

What’s more, Nguyen said some health-care facilities and personnel are flouting a provincial order that bans staff from working in more than one care facility, a leading cause of outbreaks in the first wave. “There are directives, but the challenge is to implement them,” he said. “The science is clear. We just have to do it.”

In yet another unaddressed failing, Lynch said many of the province’s 400 long-term care homes are older facilities with shared bedrooms and bathrooms, a problem that contributed to some of the worst virus outbreaks in Quebec, Ontario and other provinces.

With renovations to reduce shared spaces moving at a glacial pace, a quicker, cheaper step would be to provide more home and community care, which would reduce infections and provide an alternative to institutional living. “It’s now oriented to hospitalization,” Lynch said. “We need to redefine health care and elder care.”

Nguyen agreed. “My No. 1 recommendation is that seniors are considered the present and future of the health system. After COVID-19, there will be a different health issue. As long as we don’t recognize that

reality, we will always be behind.”

A version this article appeared in the April/May 2021 issue with the headline “No Place to Grow Old,” p. 70.

RELATED:

Two New Books Suggest a Way Forward For Canada’s Broken Long-Term Care System

Canada’s Hidden Shame: How COVID-19 Exposed Years of Systemic Neglect in Long-Term Care